December 7 is the patronal feast in Milan (St. Ambrose’s Day) and, by tradition, the day on which the Teatro alla Scala opens the new season. For 2016/2017, the inauguration was with the opera Madame Butterfly, by Giacomo Puccini (1858–1924), with Italian libretto by Luigi Illica (1857–1919) and Giuseppe Giacosa (1847–1906).

For Puccini, this Japanese tragedy—in two acts—was the result of a cultural strategy to introduce Oriental exoticism into European musical theatre. His expectations were disappointed, and the world premiere, at the Teatro alla Scala, on 17 February 1904, was a disaster. Probably, it was a sort of revenge of the detractors against the composer: they did not recognize the innovative elements of his work, ignoring his artistic effort. For the Italian audience, it was a not-understood occasion of contact with another fascinating culture.

Puccini was booed, but tried to find a remedy, saving the situation: he promptly rewrote the opera, making some relevant changes and creating a third act. On 28 May 1904, three months after the defeat in Milan, the new version of Madame Butterfly was staged at Teatro Grande in Brescia, and the revision resulted in a great success. The conductor Cleofonte Campanini (1860–1919) and the tenor Giovanni Zenatello (1876–1949), in the role of Pinkerton, were confirmed; the soprano Rosina Storchio (1876–1945), in the role of the geisha Cio-Cio-San, was replaced with Solomiya Krushelnytska (1872–1952)—a beautiful Slavic-born singer, who had married the town mayor of Viareggio, Cesare Riccioni.

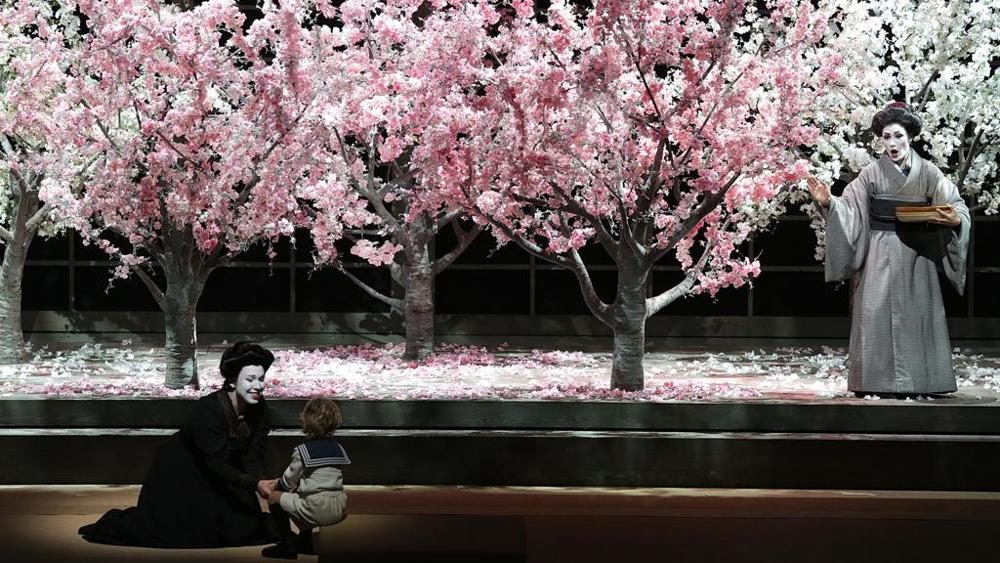

In recent years, the Italian conductor Riccardo Chailly—who is also music director at the Teatro alla Scala—has begun a critical reinterpretation of the works of Puccini. After Turandot and La Fanciulla del West (The Girl of the West), with this staging of the original version of Madame Butterfly he has paid real tribute to Puccini, expressing the hidden quality of the opera. The two-act structure is more audacious and intimate, especially in the tragic impact of the finale: probably, for the audience of the world premiere in February 1904, this dramaturgical solution—culminating in suicide through a Japanese ritual, in the presence of a blindfolded child—was excessive. After a century, we can see the experimental level of Puccini’s work, with his desire to offer a not-conventional and ambitious opera. The narrative is also cruel in its fatal development as a love story.

On the evening of 7 December, Riccardo Chailly, with the director Alvis Hermanis and the soprano Maria José Siri, received a quarter hour of applause. This staging opens an important chapter in the fortunes of Puccini in the new millennium.

Very interesting, as a related event, is the documentary exhibition at the Museum of the Teatro alla Scala (director Dr. Donatella Brunazzi) entitled Madama Butterfly, l’Oriente ritrovato (Madame Butterfly, the Discovered Orient), from 22 November 2016 to 28 February 2017 (curator Dr. Vittoria Crespi Morbio). It is an occasion for learning about the performance history of Madame Butterfly in the 20th century. Moreover, it celebrates 150 years of diplomatic relations between Italy and Japan. Finally, Puccini’s interest in Oriental culture is beginning to be appreciated and satisfied.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Maria Pia Pagani.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.