Seven bodies, moving in silence, form a slowly transitioning human landscape. The change in their shapes is almost imperceptible, like seven individual rocks that the sea gradually transforms through the slow passage of time. In this heterogeneous group of individuals, unexpected similarities arise between their bodies as part of a score-based orchestration.

It is December 2019, and the award-winning Swiss choreographer Yasmine Hugonnet is invited to the Italian city of Palermo to present her work at Biennale Arcipelago Mediterraneo (BAM), a melting pot for artists-scientists-thinkers. Extensions to which the introductory short description belongs, Se Sentir Vivant and Le Rituel des Fausses Fleurs are three choreographic works by Hugonnet that have been presented at BAM and challenge our understanding of motion and time. Considering the ephemeral nature of dance and performing arts, writing about them with a six months delay is not an attempt to dig up something that disappeared. Neither is outdated considering the great shift that the world is going through during the last six months. It is because these works seen through the eyes of today seem more than relevant. Our world that took a short pause in the course of the last months from the irresistible desire to keep on moving frenetically, has been reflected and depicted almost prophetically in Hugonnet’s microcosmos. Our indoors confinement and limited productivity made us wonder if we are alive during a moment that death became an abstract number. “How do we exist in space, time and (hi)story?” Hugonnet seems to be wondering, proposing a slowing down of movement and examining the essence of motion in a moment of diminished freedom at a global level.

Yasmine Hugonnet in “Se Sentir Vivant” at Biennale Arcipelago Mediterraneo (December 2019). Spazio Tre Navate, Cantieri Culturali Alla Zisa in Palermo, Italy. © Iolanda Carollo.

Under the title Se Sentir Vivant (To Feel Alive), Hugonnet performs a motionless monologue with a speaking body. With her internal voice and a neutral face, Hugonnet recites an excerpt from the first canto of Hell from Dante’s Divine Comedy using ventriloquism. Her voice leaves the body almost untouched. The mouth remains disconnected from the voice and the eyes stay empty. Her breathing body, articulated gestures and facial expressions distinguish life from death.

In Extensions, partially based on the movement material of Se Sentir Vivant, and in Hugonnet’s sculptural choreography Le Rituel des Fausses Fleurs, body shapes are linked and melted into each other in a way that purposefully sharpens our attention. Holding this tension in the still body gives us the possibility to observe and to associate the seemingly abstract postures into specific meaningful images of silent bodies in a process of a ritual or of unusual acrobats that lost their purpose of entertainment but remain dedicated to refining their balance.

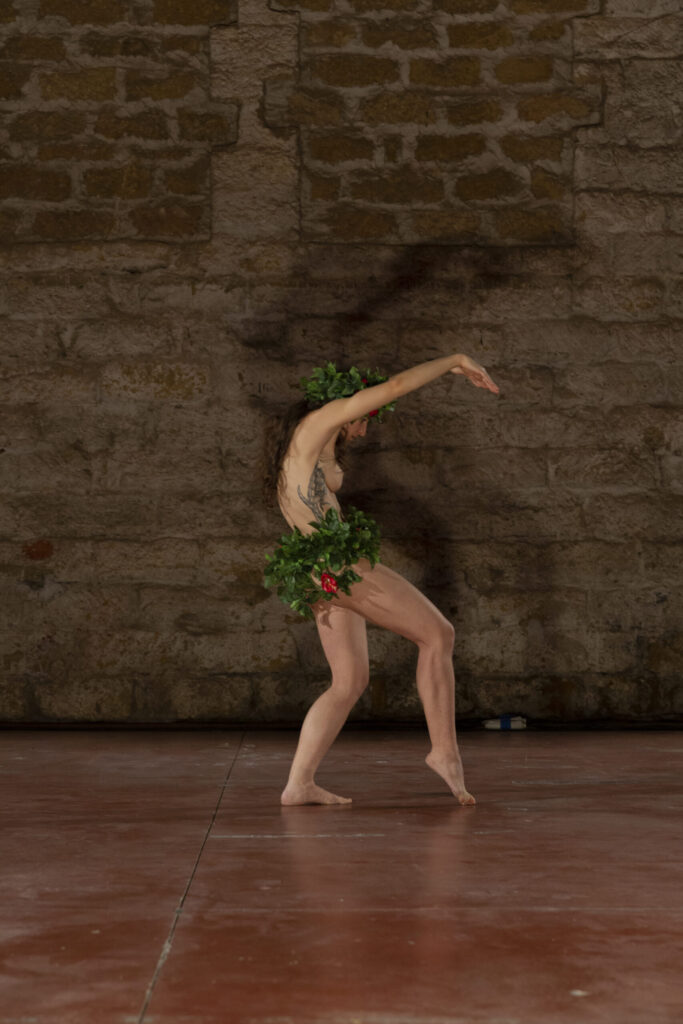

Hugonnet’s characteristic way of movement across the three works is the transitioning of the body between strenuous shapes that explore how long to linger and endure in these physically demanding human sculptures. The body has a contained dynamic. It resists moving in space and when it moves, it happens in a dense flow. Every little muscle is engaged in detail. Two-dimensional movements evoke ancient Greek bas-reliefs or even Vaslav Nijinsky in L’ Après-midi d’un faune. Body parts are magnetized, recalling a marionette controlled by its puppeteer. At the same time, they are separated in a passive-active and future-present duality while keeping whole-body connectivity. The body belongs to the dancer as well as at the space that gently supports it through distant coordinates. Time dilates and the slowness of movement almost dematerializes the body. Even if dressed only with a flower garland around the head and the waist, — as in the case of Ilaria Quaglia, the solo performer of Le Rituel des Fausses Fleurs — the controlled body becomes invisible. Although naked, it loses its gender specificity and its materiality. It becomes elastic, like rubber, before returning back to its sensuality and femininity.

Ilaria Quaglia in “Le Rituel des Fausses Fleurs” by Yasmine Hugonnet at Biennale Arcipelago Mediterraneo (December 2019). Spazio Tre Navate, Cantieri Culturali Alla Zisa in Palermo, Italy. © Iolanda Carollo.

As I go back to my notes, written in haste while watching Hugonnet’s work six months ago, I find myself in a mental state where memory and imagination blur with each other. I am reflecting on the past while experiencing the present, trying to understand what this evening was about beyond the poetic resistance of Hugonnet’s movement that now resonates stronger than before. It was the last live dance performance that I saw before the suspension of cultural production and dissemination in Italy and before a new era in which control, technology, freedom and mobility, social life and culture were, are, and will be questioned. As I sit in front of my screen, where I have watched a considerable amount of performances online, I recall what I was able to do and feel during that evening, and what I lost due to an extended mediated contact with live performance.

Performing a single task and activating more than two senses. I had the chance to dedicate myself to a specific and single event and activate very specific senses beyond the ocular.

Movement and perspective. After Hugonnet’s indication, I could move in the empty space where the performance took place; the non-theatrical space of Spazio Tre Navate in Cantieri Culturali Alla Zisa. I could change my position during the three performances (circulating around the performers, sitting at the stands and on the floor) and have a different point of view of each choreographic work. I could indulge in the atmosphere of the industrial environment and make a personal framing of the moving bodies in space.

Freedom of view. I could choose where to look. I could rest my eyes in the surrounding space and then go back to the performance and to the details of the body. I could choose where to focus my attention, when to sharpen and when to loosen it.

Meeting with strangers. I could give my congratulations face to face to the choreographer. I had the possibility to chat with people during the breaks, the end or the beginning of the performance — even though I chose not to do it.

Space sharing. I was in one space: a space to share with strangers and potentially accept their differences, their otherness. I could sense and anticipate how the others were feeling about the performance by listening to their breath and sensing the frequency of their movement in their seat.

Space and architecture. The dense flow of Hugonnet’s and the rest of the dancers’ movement emphasized the negative space, the architectural details and the aura of space. The performance happened in a non-theatrical place, which was a confirmation and a reminder that theatre and performing arts can occur almost everywhere.

Theatre and ritual. The architecture of the theatrical experience is designed as an invitation to participate in a transformation process, to momentarily disconnect ourselves from everyday life and return back to it different and hopefully better than before. The theatre, as an umbrella term for the performing arts, is a ritual, and, at its best, it transforms us. From the moment that I prepare myself to attend a performance (mentally and physically) until the moment that the performance stops resonating inside me, I am participating in the theatrical ritual. I am changing who I am. Six months later, this dance performance still stays with me and influences my way of thinking.

This list, open to additions, offers a reminder of the irreplaceable values of live dance and theatre performance as digitalization brings art into our home, as we reinvent and adapt the theatrical places to aggregate in 1 to 2 meters apart and as we get prepared to perform choreographies of discipline regarding how to cross the private and public spheres and vice versa during the phase 2 of the lockdown. Although informed by the specific experience of attending Hugonnet’s performance at BAM, most of these points apply almost to every theatrical event. Considering their universality, I hope that these observations will constitute our return to a kind of familiar normality that, as Bruno Latour suggests, connects critically with “the chains (of the past) we are ready to reconstruct” and at the same time is ready to reject “what we have decided to interrupt.”

Yasmine Hugonnet in “Se Sentir Vivant” at Biennale Arcipelago Mediterraneo (December 2019). Spazio Tre Navate, Cantieri Culturali Alla Zisa in Palermo, Italy. © Iolanda Carollo .

GENERAL INFO

The art residency of Yasmine Hugonnet in Palermo was supported by the Swiss Institution in Italy. The choreographic work Extensions has been performed by dancers from Sicily who participated in the three-day workshop given by Hugonnet in Palermo.

Biennale Arcipelago Mediterraneo (BAM), directed by Andrea Cusumano, is a collaborative project between Fondazione Merz, Transeuropa Festival and the local institutions of Palermo.

The final quote comes from Bruno Latour’s essay What protective measures can you think of so we don’t go back to the pre-crisis production model? (2020).

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Ariadne Mikou.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.