On January 8th, a group of artists and activists erected a large tent in Gwanghwamun Square and called it a theatre. Hundreds of thousands of demonstrators had gathered in this area of downtown Seoul every weekend since last October to demand the resignation of South Korean President Park Geun-Hye. This temporary structure symbolizes protest against censorship, operated by theatre artists blacklisted from government funding. It is also envisioned as a public theatre, even though its flapping canvas walls can’t keep out the noise of nearby traffic or the winter cold. Amid some the most oppressive measures leveled against the arts since the end of military dictatorship, Korean artists are currently attempting to reinstate the theatre as a public institution.

The first signs of widespread government censorship appeared in 2015. Park Geun-Hyung, a respected, award-winning playwright and director, was denied funding by Arts Council Korea at the last minute, and a production he was scheduled to direct for the National Gugak Center was abruptly canceled around the same time. Park had staged an adaptation of Aristophanes’ Birds in 2013 that caused a stir over several lines that poked fun at former President Park Chung-Hee and his daughter, who had won the presidential election earlier that year. Both President Parks had fanatic supporters—especially the father, who ruled South Korea as a military dictator for eighteen years from 1961 to 1979. Some of these groups picketed Birds for insulting Korea’s “national heroes,” while the conservative media denounced the Left’s predominance in the arts. But no one at the time imagined that the government would directly target an artist.

Park Chung-Hee’s regime ruthlessly went after anyone who spoke out against him, including theatre artists such as the late Pak Choyŏl, whose play O Chang-Gun’s Toenail (English translation available here), a satire of military culture and war, wasn’t performed until 1988, fourteen years after government officials blocked its intended premiere. As democracy stabilized in South Korea, freedom from censorship was taken for granted. This assumption melted away in late 2016 when it was shockingly revealed that the Ministry of Culture, Tourism, and Sports kept a secret list of artists to exclude from all public funding.

The immense scale and systematic execution of this blacklist, which includes the names and occupations of over nine thousand individuals, came to light during the extensive investigations into President Park and secret advisor Choi Soon-Sil’s illegal activities. The blacklist scandal made international headlines (for example, in the Economist and the New York Times) because of its relevance to the impeachment trials that are currently underway in the Constitutional Court. Since most of the artistic community opposed President Park since the election, the blacklist comprised virtually every social-minded theatre artist currently working in Korea, even including major figures with an international profile such as Lee Youn-Taek, not to mention celebrity actors such as Song Kang-Ho and Kim Hye-Soo. The Busan International Film Festival, one of the largest film festivals in Asia, lost roughly half of its subsidy in 2015 after it had screened the documentary Diving Bell against the government’s demands.

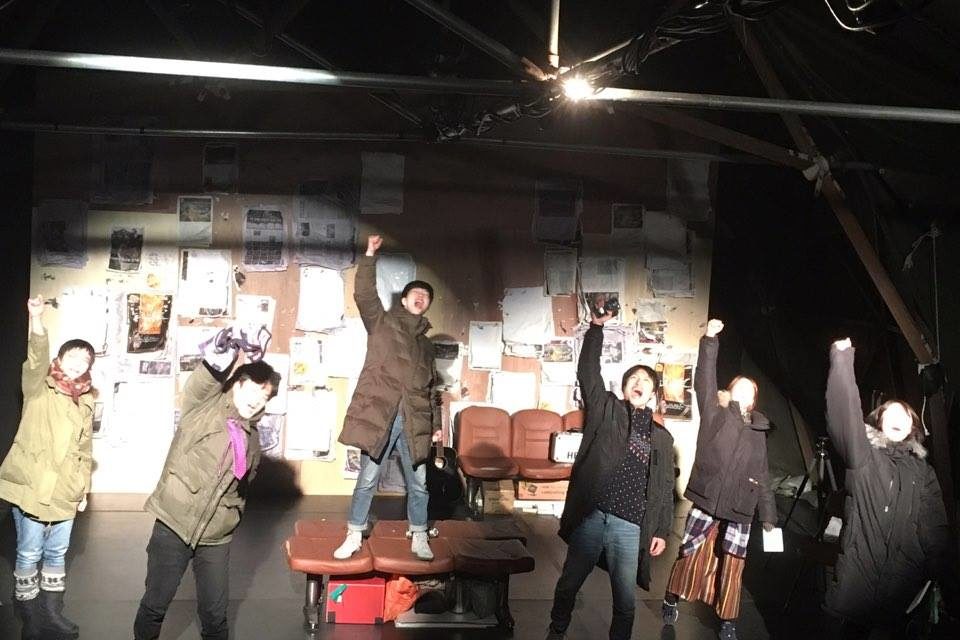

Protestors decried this insidious return of censorship and state surveillance. A group of artists continues to camp out in Gwanghwamun Square, displaying political art on the streets. However, the most significant theatrical response to the blacklisting scandal is the Black Tent project. Lee Hae-Sung from Theatre Company Gorae serves as the artistic director of Korea’s newest theatre, which will only exist until the President resigns. Artists of all disciplines and labor activists helped pitch the large, metal-frame tent that was donated by Namoodak Movement Lab, a theatre company based hours away from Seoul. On each side of the entrance sits caricature busts of two government officials chiefly responsible for overseeing the blacklist. (Both have been arrested since Black Tent was founded.) Performances are free—there is a donation basket on the way out.

Productions run at Black Tent for one week. The inaugural production was Gorae’s Red Poem, which had just ended a successful run. It was followed by plays that were noticeably more political than what people were used to seeing in Seoul’s many government funded theatres over the past few years. The Politics of Censorship: Two Citizens by the theatre company DreamPlayThese21 was actually created before details of the blacklist made the news. The piece examines the Birds controversy and its fallout from multiple angles, using the statements of government officials and politicians as part of its text. His and Her Closet was developed in collaboration with the bereaved parents of the Sewol ferry disaster that killed over three hundred people, mostly high school students. The government’s attempts to suppress bad publicity after the horrific incident and inept rescue operations (which is the subject of Diving Bell) eventually led to the blacklist’s inception. As such, His and Her Closet represents the silenced voices of both theatre artists and the families of Sewol victims demanding a clear explanation for the disaster.

Many of the companies that make up Black Tent’s open-ended season survived hand to mouth over the past few years, relying on private donations and crowdfunding, as Park’s regime tried to stamp out dissenting voices. Despite the government’s economic choke strategy, however, Black Tent had no trouble scheduling the first month’s lineup on very short notice; if anything, censorship only provoked theatre artists to work harder and resist more fiercely. Because so many artists were blacklisted, an overwhelming majority of the Korean theatre community celebrate and support the establishment of Black Tent. Indeed, this battered tent has instantly become the most important theatre in Korea right now.

Lee Hae-Sung emphasizes that Black Tent is a public theatre. It boldly claims that mantle because national theatres in President Park’s government have largely failed to fulfill their public role: to provide a space where people can tell the most important and urgent stories of the time. “Theatre should reveal truth, whether aesthetic or social. And it should be the taxpaying public that judges whether these truths are appropriate,” says Lee. This is his definition of the “publicness” that Black Tent seeks to restore. Furthermore, Lee believes that artists should pay special attention to marginalized voices in society. That is why Black Tent mentions the victims of the Sewol ferry disaster, the “comfort women,” ex-workers of massive layoffs, and the unjustly incarcerated directly in its mission statement. “We want to erect a theatre in this public square and bring back silenced voices and banished stories,” the statement reads.

In addition to hosting previously censored theatre, Black Tent also holds forums to talk to the public about how the theatre should be run. Although Lee is wary of presenting Black Tent itself as a model for a renovated public theatre, he accedes that this short-term project can be a step along the way. Playwright and director Lee Yang-Gu of Theatre Company Haein noted during one of these forums: “While this theatre may only stand in Gwanghwamun Square for the moment, the questions about public institutions that Black Tent raises are not limited to this physical space. They may linger for a very long time, since these efforts will continue when we reestablish national and public theatres in the new society we will create.”

Black Tent will be dismantled when President Park resigns, which may be as early as March if the impeachment goes through. Lee Hae-Sung and other representatives of this grand experiment are already planning their next move. They are working on a “censorship whitepaper” that will document the government’s illegal activities and the artistic community’s resistance. It is one way that the Black Tent initiative is trying to make lasting changes. “Eventually, we want the idea of Black Tent to enter Daehangro,” says Lee, referring to Seoul’s historical theatre district. In the meantime, Black Tent is at its seating capacity almost every night, giving audiences a glimpse of what the theatre could become in the near future.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Kee-Yoon Nahm.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.