After queuing outside the Cattle Depot Theatre, in the harsh yellow street light and hot weather of a Hong Kong July, to attend On and On Theatre Workshop’s production of Quai Ouest, the audience’s rushed entrance to the darkened performance space came as a relief. The cool darkness was only broken by two lights shining on the house seats. Once the capacity crowd had been hustled into their places, the two lights were killed and without a pre-show announcement, the performance began. As the audience’s eyes adjusted to the sudden change, figures materialized onstage.

The play, written by the French playwright Bernard-Marie Koltès, depicts the daily struggles of Charles and his immigrant family, who live in an abandoned warehouse near the harbor. Their life is disturbed when Koch, a wealthy man who has embezzled and lost lots of money, and Monique, his secretary, come to the pier. Koch wants to end his life, but his desire sets into motion events beyond his control that lead to dire consequences for Charles and his family.

The first twenty minutes of the show were performed with only the external yellow street light filtering through the windows to outline the actors and the set. Instead of platforms and painted flats, as one might expect the set to be constructed of, the audience was treated to the exposed walls of the Cattle Depot Theatre, a few pieces of old furniture, and scattered sand.

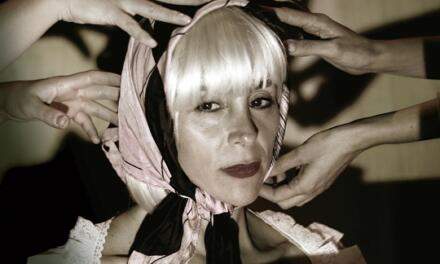

Quai Ouest. On & On Theatre Workshop and Le Theatre de Ajmer. Photo Credits: Carmen So

Lighting designer Sylvain Faye made use of light not only to denote the passage of time but also to create mood and space. A single, bare incandescent bulb defined the area of the stage where Charles’ family lived, suggesting their desperate poverty. A few semi-hidden lighting instruments activated as the show continued, painting minimal light on the sparse environment. Neither Chinese nor English surtitles were offered, thus the show lacked even the low glow of text. The absence of a discrete proscenium line separating audience and actors built the sense that the audience was crowded into a dilapidated warehouse on the harbor.

Ceci Chan played Cecile – Charles’ mother – with great control over her emotional expression. Cecile is written to be caught in an impossible position, on the verge of death throughout the play, and she managed to play her various outbursts (including slapping her child, Claire) with equal parts aplomb and agitation. In contrast to Ms. Chan’s nuanced performance, the actors who played Koch and Monique seemed to freeze their respective characters’ emotional arcs in the early scenes, perhaps as a metaphor for the emotional rut in which their lives are stuck. Only at the end of the show did we see their emotions thaw and their full arcs completed as they came to terms with their regret about the past.

The character of Fak was created primarily by channelling a tremendous amount of energy into the character’s physical movements. Fak seemed to always be in motion, as if constantly threatening to leave the warehouse. This constant movement was echoed by Charles’s younger sister Claire, but, in her, it seemed to be motivated by the restlessness of youth. A physical opposite of Fak, the mysterious character of Abad was slow-moving, and his eyes were covered for the entirety of the play. Abad’s silence was only broken for Charles, as he whispered to him in one scene. These contrasting characters served to keep the audience off-balance, not knowing what the result of these various human interactions would be.

Quai Ouest. On & On Theatre Workshop and Le Theatre de Ajmer. Photo Credits: Carmen So

A sparsely-used piano supplied live musical accompaniment, providing a perfectly timed underscore to dramatic moments. Director Franck Dimech avoided the potential pothole of excessive melodrama by limiting the use of music. The few notes plucked by the pianist mirrored the minimalist set and costumes – the piano itself looking as if it might have been discarded in the warehouse, like so much trash.

No stranger to staging violence (past credits of On and On Theatre Workshop include Sarah Kane’s Blasted, among other works) this production featured several shoves, slaps, and – most disturbingly – a rape. The moments of violence were respected with the seriousness they merited: violent actions were made more poignant by playing the gravity of the aftermath. For instance, instead of going to a blackout or the scene quickly shifting after Claire’s rape, the actress was directed to slowly walk upstage in a daze and lean against the counter, trying to make sense of the trauma she experienced. Subsequently, the audience had the option to focus on Claire or turn their attention to another scene that was starting stage left.

Quai Ouest. On & On Theatre Workshop and Le Theatre de Ajmer. Photo Credits: Carmen So

Several times the performance stumbled over the translation, which seemed to favor written Chinese phrases rather than colloquial spoken Cantonese. Monique’s multiple jarring “Jesus!” lines stood out as the only English used in the production, a choice that translator Chou Jung-Shih used to make this character distinct.

Except for the translation issues and a few well-meaning-but-odd acting choices, this production had a strong vision and communicated a message about the lengths to which a group of individuals welded together by poverty are willing to go to achieve their goals. The innovative usage of space and light in the Cattle Depot Theatre made the production stand out as a great example of how the creative use of technical elements can enhance the audience’s immersion.

Production Credits

Quai Ouest. An On & On Theatre Workshop and Le Theatre de Ajmer production. Written by: Bernard-Marie Koltès. Directed by: Franck Dimech. Translation by: Chou Jung-Shih.

Performed at the Cattle Depot Theatre from June 30-July 10th, 2017

Whit Emerson is a PhD student in the Department of Theatre, Drama, and Contemporary Dance at Indiana University. His research interests include Asian theatre and identity.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Whit Emerson.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.