On the first day of the Russian invasion, the ProEnglish Theatre in Kyiv, the only English-speaking theatre in Ukraine, transformed its premises into a bomb shelter for artists and locals. But they’re not just sheltering from the dangers of war, they’re continuing to make art for their community. Borisav Matić speaks to the director, actor, teacher and founder of the ProEnglish Theatre, Alex Borovenskiy about the current moment and the history of the theatre.

ProEnglish Theatre Transforms into Art Shelter

Like many Ukrainians on the 24th of February, Alex Borovenskiy awoke at 5 am from a call from his friend, telling him that the war started. Naturally, his first reaction was confusion and disbelief, no matter how much the talk of a potential war had been present in media in the days before. But when he heard explosions coming from the Sikorsky airport, he had little doubt left about what was going on.

Alex Borovenskiy knew that if he wanted to leave Kyiv, from a suburb on the left bank of the River Dnieper where he lived, he should have acted immediately and escaped the city while there was still no direct fighting on the ground. But then he sat down with his girlfriend and started thinking about what place he would like to be during the perilous moments of war. The answer was – ProEnglish Theatre, an independent venue that he runs in the center of Kyiv since 2018.

“Because to me, ProEnglish Theatre is my life, it’s the center of my personal universe. And plus, it’s the center of Kyiv. The decision kind of fell together like a puzzle, and we are in a basement. There is no way Ukraine would give away Kyiv,” Borovenskiy notes. “We came here by afternoon. And we stood here and some of the actors were already here. Because from the left bank it takes some time to get here.”

But it’s not just that actors of the ProEnglish Theatre came to the location, some residents from the neighborhood also came on the first day of the Russian invasion. The theatre’s premises were a bomb shelter during World War II and Borovenskiy and his colleagues rented the place because it was affordable, thus making it a safe spot from military assaults.

“On day one we hosted around 30 people and it was so strange. We felt like a refugee camp. We had families with kids, lots of cats, babushkas, these old people. And we tried to organize it somehow and make some order in this chaos, get some food, toilet and stuff as a rearranged theatre,” Alex Borovenskiy says. “We reused everything that we had, all the props. We actually had the double bed which we used for two performances, and there were kids who used this double bed.”

The decision was in a way made by itself – the ProEnglish Theatre would stay transformed as a safe haven, getting the name Art Shelter. These days there are 13 people that make the core of the shelter – like Jesus and the 12 apostles, as Borovenskiy jokes. They stay at the shelter all the time, except when some of them go out for food or medicine, also facing the bizarre wartime life on the city streets. On one hand, the residents of the shelter saw damaged buildings and even a missile being hit by Ukrainian air defenses; but on the other hand, Borovenskiy saw a place that still sells coffee and croissant. “It felt so surreal,” he says.

ProEnglish Theatre’s message concerning the Russian invasion

ProEnglish Theatre’s Rich Artistic Life before the War

Alex Borovenskiy walked me through the Art Shelter during our video call and he showed me the posters of ProEnglish Theatre’s past performances that hang on the walls of one room. Then he lead me into the performance room that would in peaceful times host an audience of 40 people, but now has 10 people living there – and cats, lots of them! The windows were nowhere to be seen, but on the theatre’s Instagram account there is a photo of a high and thick wall of English textbooks strengthening the few windows that exist there, in case any explosion happens nearby.

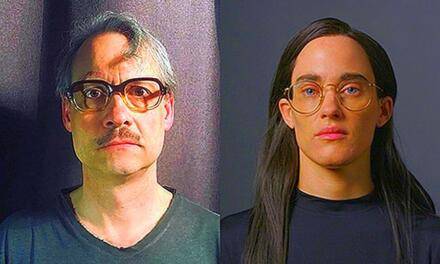

Resources at the shelter that are now utilized for safety and housing point to a rich artistic past of the theatre. Alex Borovenskiy, a director, actor and English teacher, founded the ProEnglish Theatre as the only English-speaking theatre in Ukraine. The theatre usually had 5 directors and around 20 actors working there at any given moment. It produced 15 performances, and 6 of them were on the repertoire before the war broke out. Some of the recent ones were Henrik Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler and a particularly relevant performance directed by Borovenskiy himself, Forgetting Othello.

Forgetting Othello at ProEnglish Theatre, directed by Alex Borovenskiy; photo by Joan Tian

“Forgetting Othello was a kind of a remake,” he notes. “We used the traditional textbook, William Shakespeare, and combined it with monologues of refugees from Syria and other different countries because to me, it was the question of how Europe takes these strangers in. If it does, if it doesn’t, and it was a year ago. And now, I believe, I should revive it because it’s very connected (to our current reality).”

But another significant segment of ProEnglish Theatre’s work was the drama school of acting, which also functioned completely in English. “My first education was the teacher of English and German,” Borovenskiy says. “When theatre hit me, I was already 28. So, I understood that theatre is basically what I want to do. And the only answer on which kind of theatre I’d like to do was the theatre in English. Because all my previous work was connected with something in English. I was working with multinational companies and NGOs. But I had some theatre studies as well, as an actor. Then when I started opening my own thing, English came in handy, because this is something nobody did in Ukraine.”

Since the theatre was founded in a multicultural and internationally connected city such as Kyiv, its strategy gained enough support and popularity among Ukrainians, so they continued working in both realms of theatre and drama school. “Every year we had about 100 students acting in English who eventually made performances,” Alex Borovenskiy says. “Originally, those were the kind of graduation performances of drama school, but then we run out of students and we started inviting Ukrainian professional actors who could speak English on a decent level. Right now, the theatre is about 60 percent of the best graduates of drama school and 40 percent professional actors that we get by our auditioning and casting.”

Hedda Gabler at ProEnglish Theatre, directed by Anabel Ramirez; photo by Andrii Kubrack

Although the ProEnglish Theatre is unique in being the only theatre working completely in English, it’s part of a wide and strong independent scene. “Ukraine has a very rich history of theatres, different ones. And since the 90s, when Ukraine got its independence, we have had a rich history of independent theatre which means a lot of studios, lots of drama schools, and it gets even bigger in the last couple of years,” Borovenskiy notes. “Many actors started sharing their knowledge privately, so there were a lot of drama schools opening. You could get financed not via state financing, which is very minimum, but by making money with teaching acting.”

Is There a Place for Art during War?

But now the artists of the ProEnglish Theatre are all scattered all over Ukraine, and some even farther. At the very moment, two of the directors and three actors are at the shelter, while others are at different places – some of them left Kyiv, others joined territorial defenses; some are already abroad, while others are doing volunteer work such as cooking. But the artistic team at the shelter is also keeping the artistic life at the theatre alive, as much as the situation allows. They are not only recording messages to the world but also organizing poetry readings and working on new performances.

“Right now, in Kyiv and other towns of Ukraine, there is need for basic things. Like the Maslow pyramid, first the food and shelter, then anything else. So, it feels sometimes inappropriate – when we try to do art, people talk about which house has been destroyed and who of the people you knew died,” Alex Borovenskiy notes. “But art works on an inspiring perspective. There is no pure art right now, any art is connected with war. My performance is connected with war.”

A Town in Ukraine – ProEnglish Theatre’s war remake of The House of the Rising Sun

Borovenskiy’s performance that he’s working on right now, under the working title The Sound of Cuckoo, is based on the novel The Book Thief by the Australian writer Markus Zusak. “I wrote a theatrical adaptation of it, a mono-performance. And it’s all about the small German town of Molching during World War II, and how it was bombed for three years by the Allied forces, and eventually how all the people of this town got bombed and died. And the only person who didn’t die was the little girl Liesel because at the very moment on the night of the bombing, she went downstairs to the basement to secretly read.”

Borovenskiy notes that he had never thought before of dramatizing and staging The Book Thief, but on the second day of the Russian invasion he knew this was the material he wanted to work on. “First of all, because it’s happening in Germany. Now, it’s the history in reverse. Russia pretty much does what Germany did in those times. And because there was no difference between a small town anywhere being bombed, every time is the same and people died the same way. But it’s also very humanistic because it’s about reading. And the only props we use – because we are in the shelter – are the cans of meat and the books.”

“I think it’s very important that art doesn’t stop,” Boronovskiy continues. “And it was very strange because it’s a mono-performance with a female actress, Anabel Ramirez, and we were working on the scene and it didn’t work out. But then the sirens went and it worked out just immediately. And the fun part about it – she didn’t hear the sirens. She was so much in her character, she didn’t hear it. And I did as a director, I was like, okay – it’s very strange.”

It is very hard to concretely plan any artistic events for the future during the war, and they all depend on whether there will be a full-blown attack on Kyiv. But if the situation remains similar, artists at the shelter are planning a premiere of the performance Borovenkiy is working on and they intend to continue with poetry evenings that are organized both at the shelter and online. The latest such event was on the 16th of March when people from all over Ukraine and even from the world could join and read their favorite poems.

The ProEnglish Theatre also started another poetry initiative calling on people around the world to make videos of themselves while reciting Taras Shevchenko’s poems in their local languages. Since he’s one of the most important poets in Ukrainian history, reciting Shevchenko’s poetry would show symbolic support for the Ukrainian people and their culture. The ProEnglish Theatre calls on volunteers to post their recordings on their social media profiles and send them to the theatre.

Shevchenko’s poetry is available online in Ukrainian and English, but also in German and Spanish. Nevertheless, the ProEnglish Theatre invites people to translate the poems into their local languages as means of raising awareness of the importance of Ukrainian culture in this difficult moment.

As Borovenkiy says: “Ukraine is not only the place of war, but a place of people and a place of art, and that’s important to remember.”

You can support the ProEnglish Theatre via Patreon, and follow them on Facebook and Instagram.

Related reading: Musical Theatre Actors of Ukraine in War and Mariana Bodnar from Ukrainian Musical Theatre: We Woke Up in the New Reality.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Borisav Matić.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.