Review: The Smallest Stage, by Kim Crotty for Perth Festival

A small, white rectangle taped onto the wide, open expanse of the Studio Underground playing space is a literal representation of one of the small stages evoked by the play’s title. But The Smallest Stage goes way beyond the literal to recreate its primary focus: the space between a parent telling a child a story.

Ostensibly a one-man show, actor Ben Mortley actually shares the stage with a cast of 20 others: ten children with one parent each.

These volunteers, experiencing the performance for the first time, receive their instructions (unheard by the rest of the audience) via headphones that direct their entrances and exits from the front row and stage choreography. They move props, play multiple roles, and recreate key moments referenced in the storytelling.

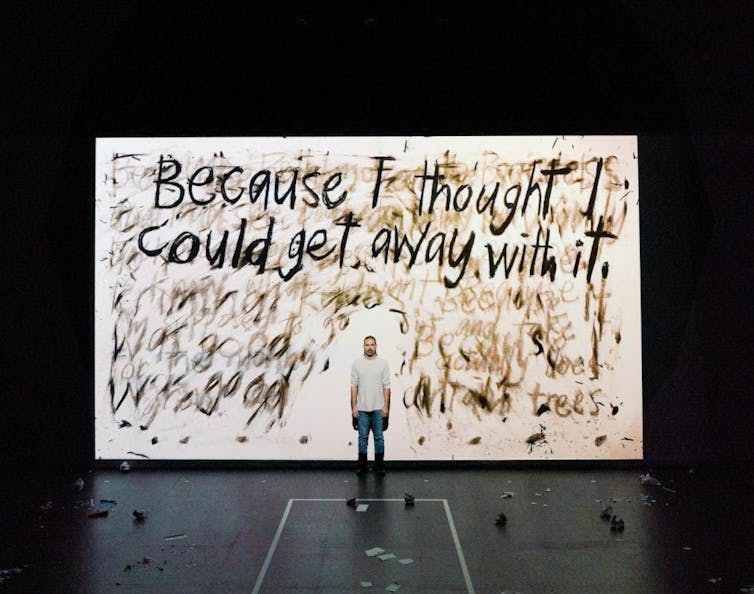

Mortley plays the character of West Australian writer and co-creator of this production, Kim Crotty, who was sentenced to two years in Dartmoor prison in the UK for growing cannabis, separating him from his partner and two sons.

In this autobiographical retelling, Mortley moves seamlessly between present-day Crotty as narrator, Crotty in the past dealing with the reality of his situation, and the characters he meets along the way.

With the white rectangle now serving as his prison cell, Crotty realizes the fleeting phone calls and visits with his children are only deepening the trauma of his absence. This drives him to do what most parents do to settle their children: tell stories.

And so, Crotty becomes both writer and illustrator, as he desperately seeks to maintain his connection with his family.

Stories as Lifebuoys

Running the gamut of children’s storytelling genres, Crotty’s stories include gross-out humor featuring unforgettable characters like Snot Man and Tissue Monster, what he calls “alternate superheroes” and old-fashioned morality tales.

All in all, he wrote and illustrated 47 stories for his sons.

Although some of them could work as children’s books or theatre in their own right, The Smallest Stage is about more than the stories themselves. It is about a father rising above his current circumstances to create new worlds to inhabit with his sons, seeking to gain a sense of control in fictional worlds that might eventually transfer to the real world.

The Smallest Stage is about a father rising above his current circumstances to create new worlds to inhabit with his sons. Perth Festival/Ben Yew.

Crotty’s stories are lifebuoys cast by a drowning man. By adding the story behind them, The Smallest Stage casts a much wider net

Even with children in the audience, The Smallest Stage doesn’t avoid serious themes. The ugly remnants of family violence, incarceration, and misogyny are faced squarely. The vestiges of what we inherit from our parents and what we pass on play out in the storytelling. Reckoning with what Crotty describes as his own “father-shaped hole,” the work tracks his journey to be a better father than the one he had.

The simple paper of the original storytelling is very much in evidence. The work brilliantly stages the transformative capacity of storytelling via live drawing segueing into animation, projection, puppetry, and a pop-up book simply lit by a hand-held torch. One extended animated story of Ghost Girl Elise is beautifully realized.

But while the stories draw us in on their own merits, the focus remains on how the stories bridge the gap between the father and his sons.

Live drawing segues into animation, projection, puppetry, and pop-up books. Perth Festival/Ben Yew.

Everyone Has a Story

This focus is also present in the presence of the audio-guided participant children and parents. Witnessing this layer of the performance illuminates the work’s premise: everyone has a story.

It also extends and expands the specificities of Crotty’s story. The choreography that accompanies the moment when Crotty is reunited with his sons when he is finally released and deported back to Australia creates a simple but emotional release. There is no acting required here.

Crotty’s decision to not hide the truth of his mistakes and failings from his children is one challenge most parents would understand. The Smallest Stage shows by finding “the words to name the ache” Crotty creates a pathway towards a more open, honest, and loving relationship with his sons, ultimately forming a lifetime habit of love and storytelling.

The Smallest Stage doesn’t hide the hard parts of the story from its young audience. Perth Festival/Ben Yew.

Mortley’s performance is an emotional slow-burn. While the work itself is expertly crafted to accommodate all the variables at play, Mortley remains at the mercy of chance created by the presence of the other participants. Retaining and calibrating the emotional arc of the work, while remaining open to the variability of their input, he is the heart and soul of The Smallest Stage’s aches and joys.

Mortley, director Matt Edgerton and designer Zoë Atkinson worked with Crotty to co-create this world premiere performance. As theatre makers, they followed Crotty’s principle of using everything at their disposal to create.

A superb collaborative effort, The Smallest Stage is a real triumph of form emerging from content, a powerful example of the originality that can emerge from a group of artists given time, money, and support to work towards one purpose.

It also reminds us of theatre’s communal roots and its capacity to activate and uplift an audience.

The Smallest Stage is at Perth Festival until February 27.

This article was originally posted to The Conversation on February 24, 2022, and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Leah Mercer.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.