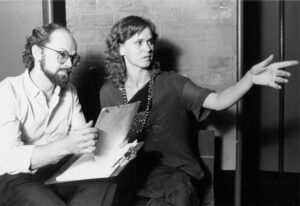

Tom Stoppard and André Previn around 1977-’78. Courtesy Mia Farrow.

Cooper Robb, an immensely knowledgeable and prolific American theater critic, who recently passed away, left behind many articles, especially in Backstage Magazine and TheaterMania, filled to the brim with facts and insights about contemporary theater. It includes a rare interview with Czech-born British playwright, Sir Tom Stoppard.

Below annotated highlights from Robb’s historic telephone interview with one of the most famous contemporary playwrights on international cooperation with André Previn—German-American pianist, composer, arranger, and conductor—about a Russian-themed production, which Robb titled “The Dissonance of Dissidents.”

The Zizkas, refugees from Czechoslovakia, bringing experimental European theater to the U.S.

A proud critic of theater in Philadelphia, a city that always lived in the shadow of New York, only two hours away, Robb points out that an important theater city like Philadelphia can trump even a major megalopolis like New York:

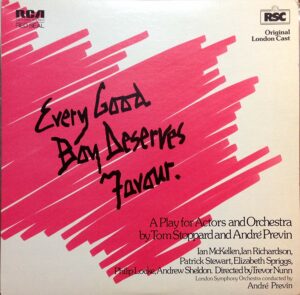

“Few theatres in America can boast a partnership as fruitful as the one between Philadelphia’s The Wilma Theater and playwright Tom Stoppard. Already a major producer of several Stoppard works, including the East Coast premiere of The Invention of Love, the Wilma and the Philadelphia Orchestra are now joining forces on a rare staging of Tom Stoppard and André Previn’s collaborative work, Every Good Boy Deserves Favor, a black comedy concerning a political prisoner and mental patient confined in a Russian insane asylum.”

Husband and wife team Blanka & Jiri Zizka, producers and directors, refugees from former Czechoslovakia, revolutionized theater in Philadelphia.

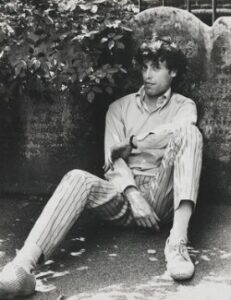

Tom Stoppard, aware of the conditions in Soviet mental asylums, in front of a gravestone. Photo by Lord Snowdon, 1966.

The Wilma, as it’s affectionately called in Philadelphia, brought more European and more experimental theater to the city of brotherly love than any other company, winning numerous Barrymore awards, the Philadelphia equivalent of the Tony awards in New York.

This husband and wife team, two theater producers and directors—refugees from (then) Czechoslovakia—stunned the city with one innovative production after another. They presented more Tom Stoppard plays than any other theater in the US, thanks to the friendship of the Zizkas with the playwright.

Below excerpts from the important interview with Tom Stoppard on international cooperation and his Russian-themed play Every Good Boy Deserves Favor:

“The Dissonance of Dissidents”

Every Good Boy Deserves Favor, Royal Shakespeare Company.

Cooper Robb: Was the script done simultaneously with the music or did the script come first?

Tom Stoppard: The script came first. I can’t read music; I can’t talk music; I can’t even hum. (Laughs) I met André [Previn] at the Greenwich Theatre where I was involved in a translation of The House of Bernarda Alba and André’s wife, Mia Farrow, was in it.

André said, “If you ever write anything with a symphony orchestra, then I’m your man.” “Oh, I’ll do that,” I said. But I didn’t have anything in mind. It took me well over a year before I actually I had an idea.

Robb: Once you talked to (Russian dissident) Victor Fainberg, it all sort of came together for you?

Stoppard: Yes, Victor and other people. I was marginally involved with various activities, which were concerned with the incarceration of Russian citizens in mental hospitals.

Former Soviet political prisoner, Viktor Fainberg, has joined Mustafa Dzhemiliev in demanding the release from a mental institution of Nadiya Savchenko as a Russian ‘court’ yet again refuses to release her from custody despite the real danger that she will die in detention.

As a matter of interest, I’ve just written a play about Russians in the 19th century (The Coast of Utopia) and, in researching that play, I’ve discovered that the practice of calling a dissident mad had this precedent in the 1830s and wasn’t invented by the Soviets. However, the Soviets put it into general use and that practice took on a much crueler form in the U.S.S.R. with quite a number of instances of people like Victor being put into asylums.

Robb: Did The Coast of Utopia change your perception of Every Good Boy?

Stoppard: Yes, in the sense it gives you a deeper understanding of where dissent came from. It’s interesting to follow the story of dissent right through to Lenin. I think Lenin was born the year that Alexander Herzen died, Herzen being the main character in The Coast of Utopia.

Robb: Every Good Boy features one of your most musical texts. Was that a conscious decision?

Stoppard: I can’t claim to have made a conscious effort to make it more musical. I write the way I write pretty much whatever I’m doing, though of course the subject and tone changes. I remember that it was very difficult to do it at all until I began, and then I did it quite quickly. André played me some piano parts, though I didn’t know essentially what (the music was) until the orchestra started rehearsing, and then it was, of course, very exciting for me.

Actors & orchestra on stage together. Every Good Boy Deserves Favor, National Theatre, 2010.

I also remember that the orchestra (the London Symphony) initially was not thrilled with these actors colonizing their space. They hadn’t been involved with anything like it. This was real theatre with three acting areas and a dramatic momentum involving half-a-dozen actors.

Trevor Nunn made this brilliant choice to begin (rehearsals) by letting the orchestra sit as an audience while the actors performed the play without music. The orchestra liked what the actors were doing, and from that moment they became wonderfully cooperative and enthusiastic. People who were formerly wondering if they could play the violin with three inches less space were suddenly volunteering to move chairs to help out an actor. It was very touching.

Robb: The play describes Alexander [Ivanov, a political dissenter, imprisoned in a Soviet mental hospital, who won’t be released until he admits that his (non-existent) mental disorder made him make accusations against the government] as a discordant note. Do you think there are too few discordant notes being heard in the United States and England?

Stoppard: I think it’s more important to note that discordant notes are part of the social and political system here [in the West]; it’s not something that gets you put in jail.

At the time I was writing Every Good Boy, I think the point I really wanted to make was that although things went wrong in the West and freedom was not perfect, and there were certainly abuses occurring, when you contrast them, you find that what is an abuse of the system in the West was a system in perfect order in the East. I would say that if I had a self-conscious message, that was it.

But the play conducts itself on the level of a black comedy, which is very frequently the response of the real dissidents, the ones who are getting it in the neck.

Robb: You obviously have a special rapport with the Wilma. Could you describe your relationship with the artistic directors, Jiri, and Blanka Zizka?

Stoppard: The Wilma is one of the very few theatres in America where I have a friendly, personal relationship. Essentially, from the time I met them at a theatre conference, I admired them. I admired the way they ran their theatre, their policy. I don’t mean doing the plays of Tom Stoppard, but I like their policy of doing new work.

And I like the fact that they’re successful, in the sense that they have a very dedicated constituency around them. And believe me, you have to earn that.

*For the complete interview, originally published by Backstage Magazine, click here.

**For the companion article about the work of an important American theater writer, click this link to “Perceptions of each other’s cultures: Open Letter to an American theater critic”

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Henrik Eger.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.