“The object of terrorism is terrorism. The object of oppression is oppression. The object of torture is torture. The object of murder is murder. The object of power is power. Now do you begin to understand me?” – George Orwell, 1984

A play that echoes trouble even before it premieres, will be remembered. The longer it is remembered, the better the chances of discussing the oppressed issues. To give it a scientific connotation, here’s Paulo Friere’s quote from his ‘Pedagogy of the Oppressed’:

“Looking at the past must only be a means of understanding more clearly of what and who they are so that they can more wisely build the future.”

I would only like to change this ‘they’ into ‘we.’

Last night, the National Theater of Kosova was packed by viewers, mostly theater artists who more than came to see the premiere of the latest play by Jeton Neziraj (who I seem to keep writing about due to being provoked by), came to make a statement: ‘we are not afraid!’ -although I bet everyone had a slight benefit of a doubt of hearing potential gunshots or maybe even being kidnapped! The premiere of the play was put at risk by a group of members of War Veterans of the Kosova Liberation Army who a day before the premiere threatened to prevent the premiere of Bordel Ballkan (Balkan Brothel) because the word had come to their ears that it was denigrating to their war and cause. Jeton’s response, as well as the response of the whole artistic community which rarely gets unified and mobilized like this time, was that a work of art can not be stopped from being produced, it can only be liked or disliked once it was viewed, in a case by case situation. A lot of people present had shown their social responsibility of opposing violence more than censorship, just by being physically present at the premiere.

I fastened my theater-seatbelt and was ready to jump into a journey full of expectations.

This time, Jeton takes the myth of Orestes who’s father Agamemnon (aka ‘The Commander’), returns to Greece after having defeated Troy. He returns as a proud winner, only to fall into the trap that his wife Clytemnestra, portrayed as a nude hiding inside a burka and her lover Aegisthus, the unpublished poet at ‘Balkan Bridges,’ have built for him.

It is hard to even believe the genius coincidence of having this play staged two days after the release of the leader of one of the biggest political parties in Kosova who had been detained in France by an extradition request from Serbia.

The subject matter of the play is the post-war period. The post-war period in ancient Greece, the post-war period in Kosova (after 1999) and a parallel between these two significantly divergent historical moments is drawn to remind us of the resemblance of ‘war’ as a concept, as a machinery of destruction that brings power to those who speak loudest. Agamemnon’s welcome anthem is a very popular Kosovar Albanian patriotic song with lyrics changed into unveiling In-Yer-Face, sharply piercing words that stigmatise the glorification of a pure war.

Both Greece and Kosova have been transformed into a Sex-Motel where the ‘hairy-boys’ who brought victory and acclaim to the country can empty out their accumulated lust and rest their fatigued bodies on Esma’s tits (a reference name to a Roma woman) that look like two snowballs.

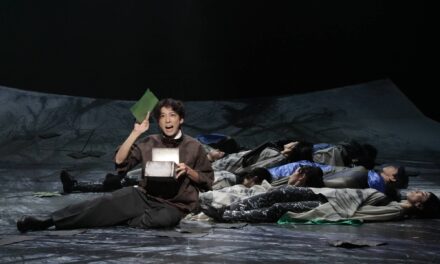

The actors deliver engulfed anger in monologues which are both tools to distance from the linear storyline and actualisations of the myth. Clytemnestra despises her husband’s ego which she believes must have duplicated after returning home with a triumph and in collaboration with her lover, Aegisthus, she kills him, only to continue being maltreated and raped by her lover this time.

Despite holding their ears with their hands due to the incredibly loud and intense performance of the actors, the viewers related to the recent history of the exaltation of power, the abuse of patriotism for profit and the trade of goods conducted between the warriors and the international ‘peace building/keeping’ community, all facts which spurred familiarity, hence a lot of laughter. Jeton’s take on his female characters is a severely double-edged sword. Clytemnestra removes her burka to reveal her almost complete nudity which shocks in the first few seconds but becomes normal thanks to actress Majlinda Kosumovic’s natural acting. So do the rape scenes which are vast. The overexposure to these situations is neutralised very fast as is our take on horrors happening in the world once we swipe down our Facebook feed pages.

Orestes, brilliantly performed by actor Armend Baloku appears towards the last quarter of the play, transformed into a very gay man who has come back from the west, to follow up on the recent death of his father (very similarly to Hamlet), accompanied by his lover. Induced by Electra who’s in a wheelchair despite being able to walk, obviously hiding her motives and seeking for her father’s affection (remember Electra’s complex?), Orestes kills his pregnant mother and her lover and the bloodshed continues. Electra who has thus far been passive and withdrawn, carrying her father’s heart on a card-box, reveals utmost tyrannical traits and her hunger for power is easily viewed in her eyes whilst Orestes falls into his well-renowned madness and hallucinates the ghosts of all the powerful figures now fallen dead. This is the beginning of his moral deterioration and it seems that he may be the only one to have any of.

Now, the weakened and confused Orestes who had been left in the shadow becomes the center of the story and brings to the table another level of abuse, this time by his lover who’s sole goals seem to be to open a dance school and promote western values. This puts a question to the form that the LGBTQ community rights in Kosova are promoted and enforced. Besides a massive amount of text emanated with tremendous stamina, the music is spontaneously merged to also entail the Balkan connotation of singing and dancing to wash away difficult situations. Jeton and director Andras Urban have brought out the best of the actors in a joint effort, strongly motivated by the political interference which gave meaning to everyone involved in making this play as well as receiving it.

Bordel Balkan is Jeton’s most compactly written play after Yue Madeleine Yue, but this time the music and the dance are organically incorporated. We unbuckle our seats from the steep roller-coaster ride to get out into the world a bit dizzy but with a sense of recognition, because we have seen everyone we recognize, maybe even ourselves on the stage. The play screams ‘We are all impure’ and unless we deal with that as the character representing the hipster on the play declares (played by Ylber Bardhi): ‘an even bigger and bloodier war will be knocking on our doors.’

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Fjolla Hoxha.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.