The cliché phrase that Buenos Aires was the Paris of South America exemplifies the exaggerated focus that elites placed on the French capital as they promoted and shaped the national identity of Argentina. Marcy E. Schwartz explains the fascination with Paris as follows: “Since the early independence period, criollo culture has had to confront and define itself with European urban models in its continuing attempt to determine political and aesthetic boundaries. The Paris written into Latin American cultural consciousness has emerged from this persistent confrontation.”

While all of Latin America’s elite were fascinated by Paris around this same time—indeed Porfirio Díaz of Mexico went into exile there on the cusp of that nation’s revolution—the link between Argentine elites and Parisian culture was especially strong. Buenos Aires served a particularly important role in connecting Paris to the rest of Latin America through publishing. Pascale Casanova’s The World Republic of Letters underscores the links between Paris as the world capital of literature and Buenos Aires, where Nicaraguan modernist writer, Rubén Dario, first published Prosas profanes in 1896. Casanova argues Dario, “rearranged the literary landscape of the Hispanic world” by importing the latest edition of modernity from Paris to Buenos Aires. Dario worked for and disseminated his work in the largest Latin American daily newspaper of the era, Buenos Aires’ La Nación.

In contrast to a large body of scholarship supporting a relationship between Paris and Buenos Aires, there is very little that discusses the relationship between Madrid, the Spanish capital, and Buenos Aires. In his study of Spanish immigration to Argentina, José Moya writes, “volumes on the ‘conquistadores’ fill shelves but not one scholarly book has been written about these more recent and more numerous [Spanish] newcomers to Buenos Aires.” In the Independence-era historiography, there is deliberate neglect of Buenos Aires’ connections to Madrid, or to Spain more generally, particularly in relation to culture. It makes sense that Argentina would distance itself from the country that had once colonized it. And that is largely what the elites did. Argentine elites looked for their national foundations outward to Paris or inward to the Pampas and the mythification of the disappearing gauchos.

Gaucho, 1868. Photo from the original article.

Julio Ramos explicitly links the writings of the Argentine elite after independence to modernity: “Beginning with the 1820s, the activity of writing became a response to the necessity of overcoming the catastrophe of war, the absence of discourse, and the annihilation of established structures in the war’s aftermath. To write, in such a world, was to forge the modernizing project; it was to civilize, to order the randomness of American ‘barbarism’.”

Domingo F. Sarmiento in his 1845 narrative Civilization and Barbarism bifurcated the political ideologies of his era into urban and rural and positioned the “civilized” city against the “barbaric” countryside: “The nineteenth century and the twelfth century coexist, the one in the cities; the other in the countryside.” Sarmiento and many of his like-minded brethren were influenced by French enlightenment thought. In particular, Sarmiento disparaged Argentina’s Spanish ancestry—absorbing the tendency in literature and history to demonize Spanish culture as uniquely backward and obscurantist. Sarmiento and other liberal elites, like Bernadino Rivadavia, advocated the de-Hispanicization of Argentina in the aftermath of independence. On the stages of Buenos Aires, however, an entirely different story might be reconstructed than the one told by the elites. This counter-narrative concerns the dominance of Spanish popular theater from the colonial era up until 1904—the first year that Argentine theatrical productions outnumbered Spanish zarzuelas.

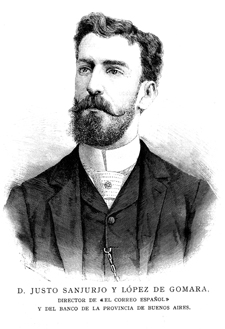

Justo López de Gomara, playwright of “De paseo en Buenos Aires”. Photo from the original article.

The main theatrical entertainment during the era of Argentine independence was a number of short musical genres that originated in Spain and which were performed by Spanish acting companies: loas, tonadillas, and sainetes. Oscar F. Urquiza Almandoz notes that in the colonial era Madrid and Lima set the standard most South American cities followed. In Madrid and Lima, a night at the theater would be loa, tonadilla, sainete, and then comedy. Loas were prologues from the Golden Era of Spanish theater that attempted to get the audience’s attention before a play began. Tonadillas was one of several small genres of music that gave rise to the zarzuela, a Spanish operetta with both sung and spoken dialogue. Sainetes (farces) were short one-act plays drawing characters from the urban working classes and employed their vernacular as well.

In 1817, the year after the nation declared independence at the Congreso de Tucumán, independence war hero Juan Martín de Pueyrredón formed La Sociedad de Buen Gusto [The Society of Good Taste] in order to harness and promote theater as a ‘civilizing’ tool. Promoting particular plays about the ‘American experience’ and about independence, the Society attempted to suppress popular theater, in particular, the Spanish tonadilla and its main instrumentation, the guitar. Audiences knew what they liked, however, and more than once demanded the return of tonadillas to the stage. The failure of the Society of Good Taste to achieve its mission speaks to the power of the ingrained customs and habits of audience members, who continued to demand Spanish tonadillas, sainetes, and zarzuelas, overdramatic or lyrical theater.

The nineteenth century was a turbulent one for Argentine nation-building and theatrical entertainment waxed and waned along with economic and political stability. Spanish-originating theater and actors remained a constant presence on Argentine stages, simmering on the back burner, so to speak until society transformed enough to sustain urban commercial theater. This would happen after 1880, the moment that the port city of Buenos Aires became designated as the federal capital, cementing its power over the provinces. Between 1879 and 1914, almost six million people came to Argentina with a little more than half of them permanently settling.

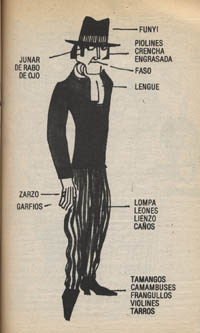

An illustration of El Comprarito. Photo from the original article.

The constancy of Spanish theatre and acting troupes in Buenos Aires throughout the nineteenth century provided a base from which the Spanish zarzuela would arise to dominate urban entertainment in the 1890s. Zarzuelas were written in Spain and often reproduced on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean in a few days. Playscripts were transmitted via the telegraph and acting companies arrived in Buenos Aires on a steamship. A touring company might leave the port city of Cádiz, Spain, arrive in Buenos Aires, rehearse, and perform in under three weeks time. Zarzuela performers were drawn to Buenos Aires for many reasons. The city had strong cultural ties to Spanish theatre and a large enough population to make a sojourn there profitable. The high season of theatre in Buenos Aires coincided with the off-season in Europe. In addition, the natural audience, Spaniards, comprised a large immigrant group in the 1880s, making up over 20 percent of the population, and could sustain upwards of ten zarzuela companies. In 1886, zarzuelas comprised 8 percent of the city’s indoor leisure time entertainment. By 1895, this number had jumped to over 60 percent.

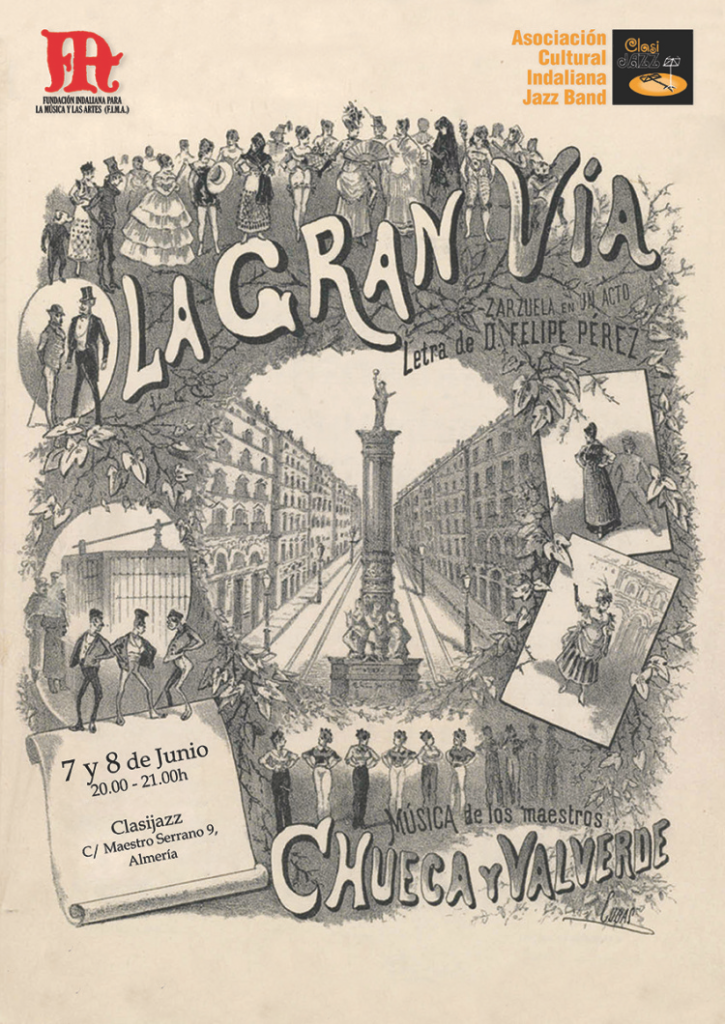

The zarzuela was an inherently urban form of theatre. Originating in Madrid, the topics of the zarzuelas were Spanish. Some of the titles centering on Madrid and the provinces of Spain: La verbena de la Paloma, de Madrid a Paris (From Madrid to Paris), La gran vía (The Great Thoroughfare), La Romeria de Miera (Miera’s Pilgrimage), Un gatito de Madrid (A Cat From Madrid), La Salamanquina (The Girl from Salamanca), and Olé Sevilla.

Spanish zarzuela companies dominated urban culture in Buenos Aires in the 1890s. They quickly began to adapt Madrid-centered themes to Argentine ones. For example, La gran vía, written by Federico Chueca (1846–1908) and Joaquín Valverde Durán (1846–1910) and first performed in Madrid in 1886, was performed in and adapted to Buenos Aires as well as Havana, Cuba and Santiago, Chile. It was even adapted and performed in the United States. The first scene of La gran vía opens with performers personifying Madrid’s streets and plazas, lamenting their fate in the face of urban renovation where a new Grand Boulevard will result in their destruction.

Photo from the original article.

Justo López de Gomara, a Spaniard by birth and prominent Spanish journalist and playwright in Argentina, debuted his play De paseo en Buenos Aires [Strolling Through Buenos Aires] as a loose adaptation of La gran vía in 1890.

De paseo travels through the quintessential institutions of Buenos Aires, from the San Martin Theatre, to the police commissary, the Plaza Victoria (later the Plaza de Mayo), the Immigrants’ Hotel, La Boca del Riachuelo, a fruit market, the port, the stock exchange, and the Avenida de Mayo [May Avenue]. It also includes local character types, like compadritos, gauchos, and Italian and Spanish immigrants, and borrows from La gran vía several allegorical representations of urban life: squabbling street sweepers and cooks, boys selling newspapers, an Italian opera singer, French chorus girls, and [yes, apparently the porteño infatuation with dogs dates back to the nineteenth century] a professional dog walker.

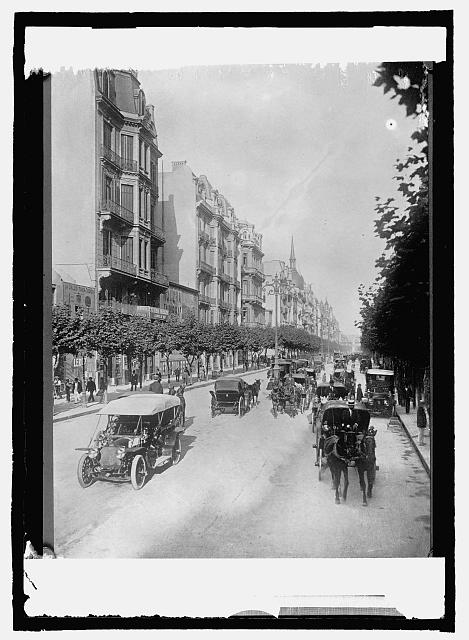

Avenida de Mayo, Buenos Aires, between 1908 and 1919, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

If in the early 1890s there was a demand for zarzuela performances to be exact replicas of those in Spain, by the decade’s end audience members were increasingly contesting performances that they viewed as inauthentic, especially in regards to the presentation of national themes and character types. The zarzuela resulted in collaborations between Argentine playwrights and Spanish actors who set the template for Argentine national theatre. It also fostered a network of intellectuals and performers who unified their work with political activism during moments of democratic openings. The genre also generated conversation and debate about what it meant to be ‘Argentine,’ as Spanish performers and Argentine playwrights colluded to create a hybrid genre known as the zarzuela criolla where Argentines wrote the plays and Spaniards performed them.

If zarzuela performers tended to integrate themselves smoothly with Argentine audiences most of the year, twice a year it was impossible to forget the historical relationship between the two countries: May 25 and July 9, Argentina’s two days celebrating important moments in their independence from Spain. During independence days, theatres were decked out in the national colors of whichever nation was being celebrated. Streamers were hung, national anthems were sung. As such, theatres were arenas where patriotic gestures and national traditions were embraced and displayed. In addition, theatres were largely masculine spaces and young elite men went there to enact their own sense of manhood by protecting (and over-interpreting) slights to Argentine national identity. The fact that Spanish performers were required to sing the Argentine national anthem, which included lyrics derogatory against Spain also assured that theatres would be loaded affairs on these days.

El Comprarito. Photo from original article.

The preponderance of Spanish performers on Argentine stages resulted in the curious case of the first actor to dance the tango on the stages of Buenos Aires: a Spaniard that performed in blackface. Ezequiel Soria’s Justicia criolla[Creole Justice] (1897) is a Spanish zarzuela that focuses on Benito, an Afro-Argentine doorman for the national congress who peppers his dialogue with political commentary and who also attempts to seduce Juanita, a white Argentine woman. Benito’s primary characteristics are his flirtatiousness, verbosity, and musicality. Benito is famously remembered for being the character credited with introducing the tango to the stages of Buenos Aires. Enrique Gil, an actor from Spain, who directed theater in Buenos Aires, first played Benito.

It was inevitable that the Spanish zarzuela would decline as Argentine theatre matured. 1904 was the last year that the zarzuela genre dominated in Buenos Aires. After the passage of a law that gave Argentine writers a guaranteed 10% of the box office for their plays, something which Spanish writers had secured in 1890, the Argentine national theatre became a relatively lucrative business. While Buenos Aires has often been referred to as the Paris of South America, throughout the nineteenth century in matters of popular culture, Buenos Aires looked towards Madrid.

This article was originally published by The Metropole and has been republished with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Kirsten McCleary.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.