“Just look at the origins of the festival – it was part of the European project” – Edinburgh International Festival director Fergus Linehan Photo Credit: Eoin Carey

In 1947 Edinburgh was still in a post-war haze. The city was craving colour, culture, and above all, fun. Then came the International Festival with a simple remit: to “provide a platform for the flowering of the human spirit.” Director Fergus Linehan laughs a little when he repeats this motto now. Seventy years on, he believes the world is in need of as much relief as it was back then. “When we started talking about this a few years ago, we thought that we really didn’t want to talk about the flowering of the human spirit in 1947, because it sounds nostalgic,” he says at EIF’s 2017 launch. But with Brexit, the resurfacing question of Scottish independence, and the constant discussion and debate surrounding migrants and refugees, a festival with its roots in internationalism is certainly in a unique position.

EIF opening event Bloom will take over an as-yet-unannounced “precinct” of the city – and will be produced by 59 Productions, who also worked on the Harmonium Project and Deep Time

Internationalism in the time of Brexit

“As the planning for this festival went on over the last couple of years,” Linehan says, “all of these questions came up – about Scottish identity, British identity and European identity. Once they were these abstract ideas, but now they’re things that we’ve got to make daily choices on. “I am an EU citizen living in Scotland – what’s that going to mean? These are tangible day-to-day things that are going to affect us.” Those things considered, he says, the festival’s nostalgia for their original motto “became much more pointed.” He describes the last 12 months as politically “gruelling”, and he wants to address that. But just like in 1947, he says, “it’s time for a party – there’s no doubt we’re due one.”

‘It’s very hard not to be political at the moment’

The party, as it were, is for everyone. This year, as always, the message is that the world is welcome in Edinburgh. There are definite political overtones, but as Linehan says, “it’s very hard not be political at the moment.” “Just look at the origins of the festival – it was part of the European project. It was part of the whole emergence of the need to think about Europe. Obviously, back then there had been huge migrations of people. It’s relevant.”

The festival’s founder Rudolf Bing was a refugee. An Austrian-born opera impresario, he worked in Germany before becoming a British citizen in 1946. He was knighted in 1971. The festival’s message of inclusiveness started with Bing and is being continued to this day. “Hopefully,” Linehan says, “the festival is more humanist than overtly political. We’re not specifically talking about Brexit. We’re talking about the rise of authoritarian behaviour and what that looks like. “Yes, it’s political. But it’s political in the human sense, rather than literally referring to things in today’s news.”

A programme that throws back to 1947

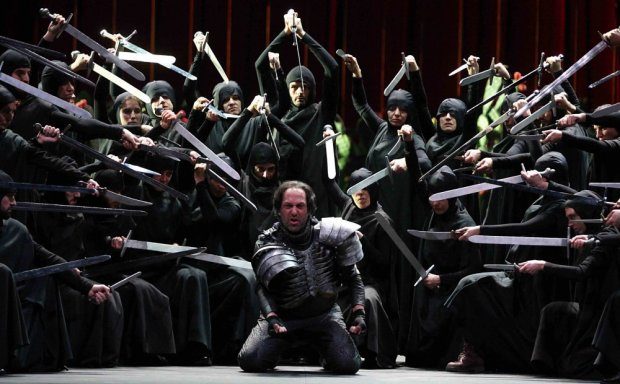

This year’s programming is a 70-year nostalgic bonanza, which highlights the origins of the event, as well as its current strengths. Since founder Bing was heavily involved in opera, this section of the programme is particularly well-supported. There are nine in total, and highlights include Verdi’s Macbeth and Puccini’s La Boheme. The Opening Concert, Haydn’s Symphony No 94 ‘Surprise’ is a nod to the fact that it was the first piece to ever be performed at the festival. And The Old Vic, so heavily involved in the theatre side of the programming throughout the festival’s history, is front and centre in the performance strand. Most notably, they are championing the world-premiere of The Divide, by renowned playwright Alan Ayckbourn.

‘A city of Edinburgh’s size shouldn’t have a festival like this’

That the festival can be so heavily nostalgic for its own programming is a testament to its strength. But the continued success of EIF, Linehan believes, is in part down to the city of Edinburgh itself. “Really, a city like Edinburgh of its size shouldn’t have a festival like this”, he says. “Most cities of this size have got a little thing where people put up some bunting. Edinburgh’s got the equivalent of the very best of New York, Paris or London. “We never forget for one minute that it’s the people of Edinburgh and Scotland that pay for this. I think Edinburgh’s always had that sense of being a relatively small city which perceives itself as being of international standard. “And if you’re living in Edinburgh and you’ve been out to the festival, then you’ve seen everyone. It creates this very sophisticated audience, and it puts Edinburgh on the world map.”

Every year, the festival finishes with the a fireworks concert in the centre of Edinburgh Photo Credit: EIF

As for the future, Linehan believes there will “absolutely” still be a festival in another 70 years – regardless of politics. “If you’ve got large numbers of Edinburgers who feel this is for them, who are excited about it, then it’ll be fine. Politics will always follow the concerns of people.”

This article was first published at www.inews.co.uk. Reposted with permission. Read the original here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Rebecca Monks.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.