A curved, declivitous, dark-grey hill, built from large, rectangular vinyl blocks–reminiscent of an earth-covered rubbish tip, a graveyard or even the lifeless surface of a planet–this layered, dead landscape is the set of the acclaimed Greek experimental choreographer-director Dimitris Papaioannou’s dance theatre performance The Great Tamer.

The title refers to a Greek proverb, according to which time is the great tamer, and in this 100-minute show, Papaioannou’s dancers explore this sloped landscape to reveal what lies beneath a human waste yard. At the center of the investigation is the human figure, the naked body, its identity, and cultural memory. Papaioannou’s fascination with the beauty of the nude, from skin tone to the shape of body parts, and his ergonomic but powerful compositions of colors for the stage recall his past as a painter.

The ensuing performance is a postmodern post-mortem, an absurd yet melancholy excavation of the remnants of a once powerful European culture.

The vinyl layers of the set are peeled off (set design: Tina Tzoka), and from below the hollows and hidden trapdoors, objects such as rocks, bones, water, and body parts are excavated. These found objects or torsos are then assembled into expressive, often grotesque “moving pictures,” many of them recalling (or playfully parodying) iconic paintings from European art (the works of Botticelli, Goya, El Greco, Rembrandt, and Magritte) or reminiscent of the iconography of Greek myths from the cradle of Europe (Demeter, Narcissus, Venus, Atlas, etc.).

Revealing and covering are the main motifs of the performance, from its comical entrée of two men’s conflicting aims of covering or uncovering with a white sheet a naked male body lying in the pose of Mantegna’s Lamentation Of Christ, whilst Johan Strauss’s popular Blue Danube waltz is played slowly and distortedly. The image offers multiple interpretations–and recalls a variety of cultural contexts, from Jesus to Everyman to even 20th-century performance-happenings–depending on the cultural memory of the viewer.

“If things are not carefully and very cautiously covered–they will never be discovered,” comes to mind Lorca’s line.

The boots that belonged to the naked man stand abandoned downstage. After the slapstick-style execution of the previous scene, they might even recall Chaplin’s boots. There is something vulnerable about them. A man approaches the boots, removes his shoes and puts his feet into the abandoned ones, but when he tries to walk away, it turns out, the boots are rooted to the ground. With some effort he frees the footwear, then makes a handstand and exits the scene upside down, walking on his hands, with the roots dangling off the boots. The associations which sprout from this scene are rich: from the notion of the (im)possibility of walking in someone else’s shoes to the metaphor of our rootedness in our history, heritage, and culture.

A retro-spaceman, wearing the Apollo astronauts’ iconic spacesuit, walks in slowly to center stage with heavy, wobbly steps; we can hear his labored breathing through the amplifying system. In the middle of the stage he stops, and with great effort, begins digging with his hands, until from the ground he unearths a Christ-like naked figure. His colleague appears, approaches the body, removes her helmet, opens her spacesuit and puts the naked young man on her breast.

Later in the show, in another scene, a bearded dancer re-enacts Goya’s painting Saturn Devouring His Son, but the figure in his hands this time is a puppet version of the spaceman we saw earlier. Saturn (or Kronos, in the original Greek version of the myth) is known to be the God of time–the great tamer, in whose hands we will all (bodies, artifacts, technical inventions, people, and countries) come to an inevitable end and decay.

Papaioannou’s dance theatre uses a visual, surreal, dreamlike language that is similar to the late Pina Bausch’s work–no surprise that earlier this year he was commissioned to create the Wuppertal Tanztheater’s New Piece I, the first full-length work for the company since the untimely death of their founder. Yet the similarity between these two artists is formal rather than substantial. It is certainly true that the set (the hill that takes up most of the stage and against which the dancers have to work, making every movement an effort), the style of the costumes (the formal attire: besuited men, women wearing black dresses and high heels), the grotesque humour, the handling of time (slow movements, repetitions), the marked performativity (reminiscent of a circus performance) and the turning away from the accepted vocabulary of dance are qualities that are so familiar from Bausch’s work.

However, there are significant differences between the two choreographers’ work. While both use simultaneous actions on stage, Bausch decidedly did not differentiate between these synchronized events, whereas Papaioannou’s dramaturgy is much more linear and focused. In Papaioannou’s compositions, there is a hierarchy between the simultaneous events; and Papaioannou is clearly directing the audience’s gaze in a more controlled way, almost insisting on a narrative that he intends to tell. Perhaps this direct decisiveness also contributes to the show’s more masculine and virile atmosphere. (The performance featured seven male and three female dancers.)

Another substantial difference is the approach to dance of the two director-choreographers. In collaborating with her ensemble, Bausch worked from the inside, using the inner experience of the dancers as a starting point, exploring (as she famously said) “what makes people move.” Papaioannou’s dance theatre, however, seems to operate from the outside: the dancers on the stage are not expressive personalities but rather vehicles, bodies to explore kinetically a vocabulary built from an existing iconography of famous European artworks, and to help create a dynamic collage from them. Papaioannou’s work is a moving panopticon of archetypical yet fragmented images, composed from the decayed building blocks of our common cultural heritage.

Perhaps because of his use of these familiar and visually captivating images from our common cultural subconscious, the show feels like a blockbuster in contemporary dance theatre, selling out Sadler’s Wells to the very last seat. It is to Papaioannou’s credit that he can make important contemporary work that speaks to the masses. However, once the message of the performance “lands,” the rest of the show feels slightly overindulgent, a baroque proliferation of variations on the same topic. As fascinating and original as these images are, and as much as the world of Papaioannou’s piece is truly unique, the show felt 15 to 20 minutes too long.

An important consequence of this aestheticized, fine-art-driven approach to dance theatre is that the dancers’ personalities seem negligible in Papaioannou’s ensemble work; the emphasis is rather on the images which he creates on stage with the help of their bodies, their movements, object puppetry or finely coordinated group work. Therefore, the dancers are more or less replaceable or interchangeable–there isn’t one who would stand out from this clockwork-like, finely tuned ensemble work: regretfully, there are no dancers’ personalities or names we remember. This is certainly a choreographer’s prerogative; however, I found it disconcerting in the case of the three female dancers, who played more decorative roles, and whose stage presences seemed almost interchangeable.

From all these stunningly choreographed, slowly unfolding, “dynamic tableaus” and physical trompe-l’oeils with which Papaioannou stunned and enchanted his London audience, perhaps the “vogue” solo of one of the male dancers–his fast and intricate, contorted hand and arm movements gave a short but stunning insight into how technically accomplished these dancers are.

The show ends on a melancholy vanitas image: a skull is placed on a codex downstage, next to it are an orange and its peeled skin. Behind it, centre stage, a man is blowing a piece of light golden foil, trying to keep it up in the air–as if to show the vulnerability and futility of the common cultural heritage of Europe, this “graceful, unexpected and heroic folly” (to quote essayist Antal Szerb), before it disappears forever through the trapdoor of history.

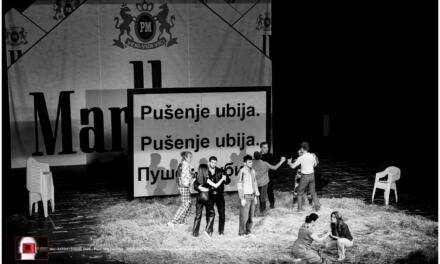

The Great Tamer, by Dimitris Papaioannou. Photo by Julian Mommert.

The Great Tamer, by Dimitris Papaioannou

Conceived, Visualized, and Directed by Dimitris Papaioannou

With: Pavlina Andriopoulou, Costas Chrysafidis, Dimitris Kitsos, Ioannis Michos, Evangelia Randou, Kalliopi Simou, Drossos Skotis, Christos Strinopoulos, Yorgos Tsiantoulas, Alex Vangelis

Set design and Art Direction: Tina Tzoka

Costumes: Aggelos Mendis

Lighting: Evina Vassilakopolou

Sound: Kostas Michopoulos

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Katalin Trencsényi.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.