Continental drama, in this era of Brexit negotiations, seems to be rarer and rarer on British stages. But, luckily, there are some venues which buck this parochial trend. The Gate Theatre in Notting Hill, with its current production of Jean-Pierre Baro’s Suzy Storck, is one such; another is the Orange Tree Theatre in Richmond. This Off-West End theatre, led by its artistic director Paul Miller, has an exceptional record in welcoming voices from the rest of Europe. This year, there have been plays from Germany and France, and now from the Netherlands.

Lot Vekemans is an award-winning Dutch playwright and novelist who has had major successes there and in Germany. Her play Gif (Poison) premiered at NTGent in the Ghent, Flemish Belgium, in 2009. It is set in the waiting room of a completely nondescript cemetery, with only a water cooler and a coffee machine, all given a suitably bare and frosty feel in Simon Daw’s sensitive design. Here a nameless man and woman meet: they are the bereaved parents of a little boy who was killed by a car nine years ago. They have been separated for some seven years, ever since he walked out on her on New Year’s Eve, without giving any explanation or any way of contacting him.

Now, she has reached out to him, getting his address from his mother, ostensibly because the cemetery has had some problems with contaminated soil—hence the play’s title—and plans to rebury 200 of the bodies in its care. But the title is also metaphoric, and the encounter of two people, who were once intimate and now are completely detached, explores the way that an unexpected tragic event can have a venomous effect on a relationship, resulting in a toxic contamination of the best human qualities and a paralysis of the will to change. Following such an emotional disaster, can anyone ever really move on?

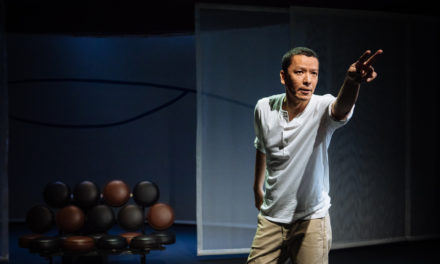

Starting with the couple’s uneasy meeting, their personalities familiar to each other, yet also tentative, the long years of separation imposing a wary quality to their interactions, the 80-minute two-hander circles around their different experiences of catastrophic loss and slow-burning sadness. In Miller’s deeply felt production, Zubin Varla and Claire Price show how their characters have dealt with the worst thing that could have happened to them. He is a journalist who has relocated to Normandy and remarried, and now plans to write a book about his experience of loss, dotting Is and crossing Ts, and finding a full stop to the mess of emotions. She has remained disabled by loss, unable to forget or move on, moving through life as in a dream, dependent on sleeping pills and a succession of therapists.

For a while, Vekemans seems to suggest that the differences between He and She are all to do with gender. Men are more cerebral, women more emotional; He is closed in; She is still raw to the touch. Men fix things; women feel them. Men can move on; women are trapped. Men can kick the habit of grief; women are addicted. But gradually, along with a surprising plot twist, the two emerge more as individuals, and it’s their increasingly engaged interaction that builds up during the play’s later stages. Moving on may or may not be possible, but it needs personal contact rather than distance and silence to move forward. In one brief moment, the couple shares cheese and wine, and it almost feels like a small communion, a temporary blessing.

The cool blue color of the set enhances the coolness of Vekeman’s text, translated by Rina Vergano, which has a detached flavor all of its own. It’s more of chilly philosophical meditation, in which ideas about grieving and bereavement are discussed, rather than a full-on clash of egos, and both the roar of vicious emotion and the laxative of laughter are absent here. It is a slightly frosty play rather than a red-hot one, but the acting brings it alive. Varla is totally convincing as the anxious, articulate, well-grounded and apparently self-sufficient He, while Price is at first more flighty, more distracted and more generous with her smiles. Her personality changes, however, during the performance, and we end up with two people who are very much two sides of the same human coin. They are linked forever, and they know it. This study of emotional damage offers a severe, but satisfying evening.

This post originally appeared in Aleks Sierz on November 13, 2017, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Aleks Sierz.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.