Riel’s real purpose in the opera is not to stand up for his people as much as it is to transfer a kind of Indigeneity to Canadians, the medium through which Canada becomes Indigenous. In this sense, Louis Riel is a lot like a Canadian version of Henry Wadsworth’s Longfellow’s “The Song of Hiawatha,” a 1855 epic poem about a noble Indigenous leader who, before he and his people recede into the mists of history, he sits down with some strangers—representing Americans as a whole—to gift them his lands, his culture, and his primordial connection to the continent. (This mythic Hiawatha of course, should not be confused with the actual Hiawatha who was the founder of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, and predates Longfellow by centuries).

With its pretension to indigenize Americans by replacing those already there, the Song of Hiawatha is an indigenization fantasy, a tale for settlers by settlers that allows them to imagine themselves in possession of a continent that was “given to them,” instead of it being taken from others. Riel, like the mythic Hiawatha, is portrayed as making the same bequest to Canada—at the moment of his death Canadians with inherited Indigenous lands, culture, and, these new progressive made-in-Canada values of the 1960s that Riel is supposed to represent—bilingualism, multiculturalism, a voice for all people. Riel is the vessel through which this great inheritance occurs.

Riel is the classical tragic hero, he’s identifiable, sympathetic, but also doomed to fail for reasons outside of his control. It’s clear that the audience is meant to identify with Riel, and not their actual countrymen. The 19thcentury Ontario public—the real cultural ancestors of the Opera’s target audience—are depicted as riotous Organemen denouncing Riel and singing a song alluding to his lynching. Also contrasted to Riel’s sympathetic character, are the largely unrelatable nation-builders of Canada, Macdonald and Cartier, whose policies and vision had a much greater influence on modern Canada than any myth-making about Riel ever could. Nobody is cheering for Sir John A. He is scheming, duplicitous, sometimes drunk, and always sinister.

Perhaps the audience’s identification with Riel is why most Indigenous characters are silent, because if Indigenous characters were to more clearly articulate their political visions for ongoing Indigenous independence in their homelands, that their relatability to this mostly non-Indigenous audience would evaporate. Perhaps they are silent because of the audience, in the act of identifying with the Métis, are in essence taking their place, Métis are voiceless because the audience fills the void with their own internal monolog.

In some ways, the work is an indictment of Canada, at least a certain version of Canada. In no place is this more evident than in the third act, as Riel’s sham of a trial rams through a guilty verdict. The Parliamentary Chorus, joined by General Middleton and the judge, shout condemnations from their benches to Riel below. It is at this fever pitch, that Canadians are meant to identify with a romantic Métis resistance to old world conservative values.

As Riel is strung up and sings his last, the opera ends awkwardly. The crowd erupts, applauding his death, the final act before the curtain drops. I found this moment incredibly uncomfortable, as this is certainly a tragic day for the Métis, indeed we mark the occasion on its anniversary every year. But this is not only a tragedy for Canadians, it is a martyrdom that inspires a new vision for Canada.

In the opera, Canadians are invited to become Métis, struggling against powerful and unresponsive conservative political forces. Rejecting an old world political vision, the progressive values in which Riel’s struggle represents cement Canada as a “Métis” society, a mixture of old world and new, a theme I heard from many opera goers afterward.

It is clear from the outset that this story is not aimed at an Indigenous audience, after all not many Native people go to the opera. But this isn’t really a Métis story either. It’s a Canadian one. The biggest irony of the mythmaking of Louis Riel is that the opera flies in the face of what Riel actually fought for: an ongoing and independent Métis nation. He wanted his people to be respected as a political entity that would continue to live freely either inside of Canada (with a new province of Manitoba that never materialized for us) or as part of an independent Indigenous Confederacy when Canada proved unwilling to respect our sovereignty.

Riel’s actual vision is spelled out rather clearly in his Last Memoir from October 1885, in which he insists that Métis sovereignty persists, despite Canada’s claims otherwise. The Dominion, he writes, “laid its hands on the land of the Métis as if it were its own” and with armed force “even took away their right to use it.” He declares that according to the law of nations, only consent can lead to one people governing another, arguing that “the Canadian Government cannot become trustee [of the Métis nation] unless by the consent of the people. Because this consent had neither been asked nor given, the Council of the Métis … their Laws of the Prairie continued to be the true government and the true laws of that country, as they virtually still are today.”

If the opera ended with these words, it would, of course, be incompatible with its own mythmaking, it would not aspire to new made-in-Canada values represented by a mythic (but not real) Riel. The opera does not ask the audience to realize Riel’s real vision, it asks them to adopt a thoroughly Canadianized vision of him. In true “Song of Hiawatha” fashion, the actual historical figure of Hiawatha is replaced with a mythologized version, reinforcing the dominance of these settler societies, rather than challenging them.

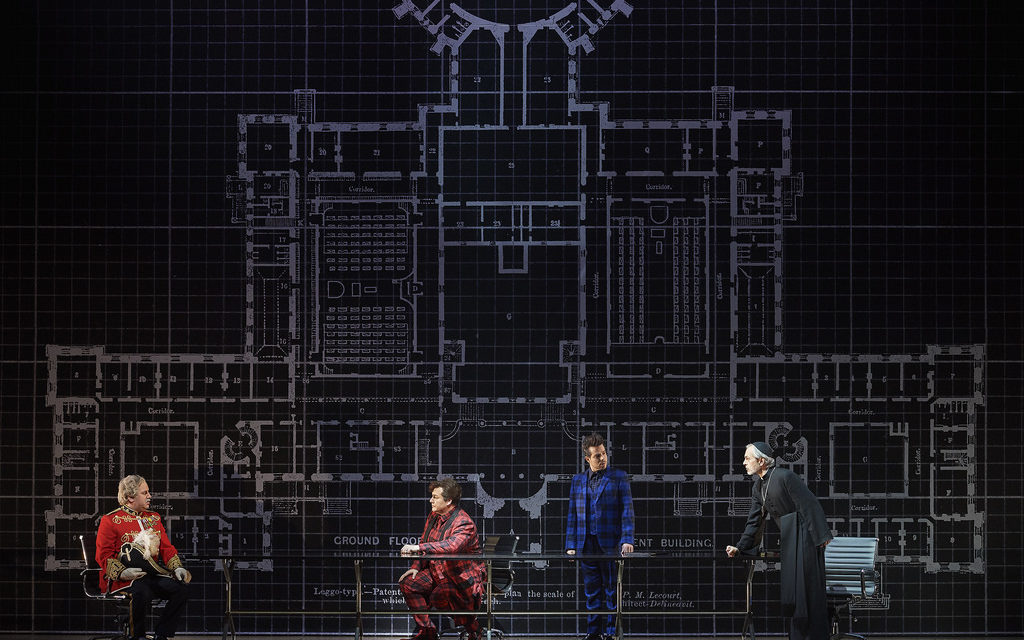

So who owns Riel? In this case, presumably, Canadians do, just as they own his slightly-altered public domain image used for the opera’s set. Just like the opera’s composer presumes to own a Nisga’a lament song that he appropriated from an anthropological study. In essence, the opera assumes to have inherited these things, symbolically at least, but also on a legal level. Much as Canada presumes to have inherited Indigenous lands.

The opera then is part fantasy, part declaration of sovereignty. It’s a work that features silent Indigenous people and vocal Canadians, and at its finale, Riel doesn’t really get the final word, even if he’s the last to sing. The real final word really goes to Macdonald, who as Riel’s world is crumbling proceeds to narrate the actual future of Canada, in this sense the opera allows Canada to have its cake and eat it too. Canada can at once benefit from the undeniable genocidal vision of Macdonald whose government sought to clear the West of the Indigenous nations, while also being Indigenized by Riel, identifying with a romanticized Indigenous struggle in which they are allied with the protagonist, not the inheritors of what was taken from us.

As Albert Braz notes, “If Riel becomes a Canadian patriot by opposing the federal government, what is the national status of the volunteers who battled him on behalf of that government—traitors? Indeed, it is probably not an accident that the 1885 volunteers have vanished from the consciousness of Canadians.” Indeed, this opera invites its audience to exorcise the inconvenient spectre of Canadian anti-indigenous violence and instead embrace a new set of made-in-Canada values, mixed European and Indigenous, as if they were all Métis through the martyrdom of Riel.

Adam Gaudry, Ph.D. is an assistant professor in the Faculty of Native Studies and Department of Political Science at the University of Alberta. His research focuses on Métis politics, history, and identity, and often writes about how these things are portrayed in Canadian arts and culture.

Originally published on adamgaudry.wordpress.com. Republished with kind permission of the author.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Adam Gaudry.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.