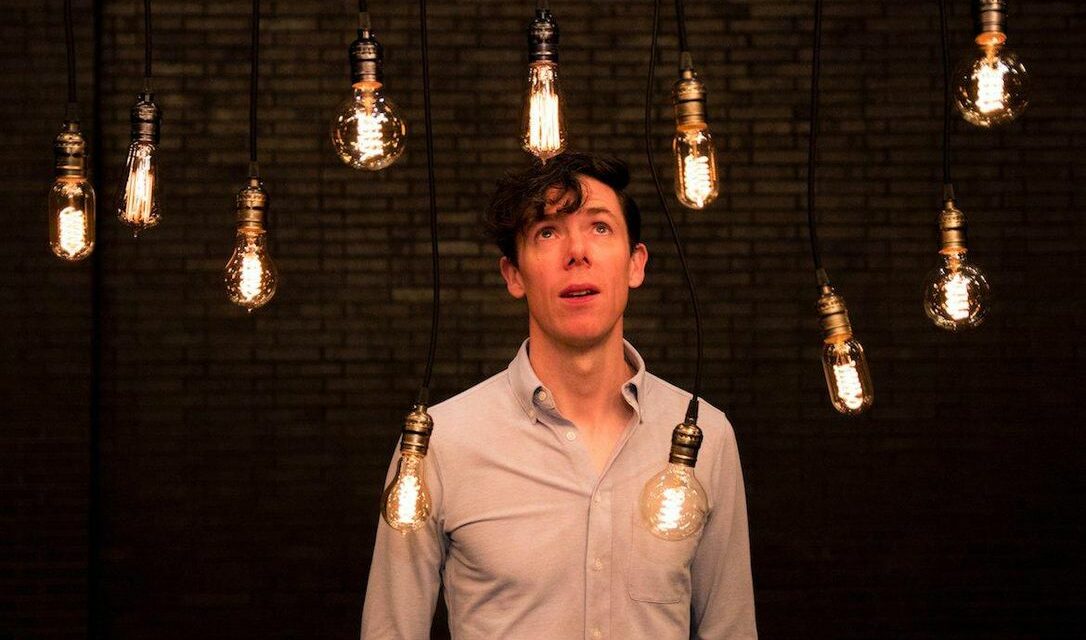

“I want to believe,” declared Agent Fox Mulder in the 1998 television pilot for The X-Files. Two decades later, the question of who gets to believe—in a world where not all testimonies are born equal—drives forth Damien Atkins’ We Are Not Alone. In this one-man show at Crow’s Theatre, writer and actor Atkins’ elastic performance gracefully brings the show to life, but his story fumbles towards a dangerously sweet conclusion.

We Are Not Alone directs a skylight towards the evolution of modern storytelling itself. Beginning with the alien craze of the 1950s and ending with Atkins’ writerly visit to a paranormal science convention, UFOS are merely the guiding star through which he takes us on a tour of what radio talkies, history books, and first-person accounts have to say about life on Earth and beyond. With his agile impersonations of interview subjects, he encourages the audience to empathize with UFO-spotters as a genre of storyteller, and he offers many a lens through which to look at the lookers: the humorous, the tragic, the academic, the digestive, and so on. Un-spotlighted perspectives hover uneasily above his comedic efforts, however.

Now, did Atkins write the one-man show equivalent of a “Trump County” sympathy piece? I’m not sure yet. His plot certainly echoes the troubling journalistic trope: a white northern-based ethnographer (himself) ventures to the American south and offers a platform for the folksy, lower-class, white-coded people to voice their “alternative” take on our universe and the “aliens” in it. In doing so, the show divorces the world of conspiracy theories from our present world of uglier historical contexts. For Atkins, these testimonies are deeply personal, quirky life-story fodder. This aversion to conventional evidence never registers onstage as a political dog-whistle-cum-kiln for kegs of “post-truth” ideology, which have their place in less savory parts of American history. In recent years, for example, critics have become cognizant of the overlap between those who fixate on intelligent life outside of Earth, and people who think that Egyptian pyramids must have been made by UFOs, rather than intelligent Africans. If We Are Not Alone suffers one galaxy-sized flaw, it’s the show’s hesitation to truly politicize the personal.

Audiences might be forgiven if they do not register the relationship between UFO conspiracy theories as adjacent to fringe cultures of white supremacy and imagined new world orders. Other audience members might be forgiven for not fully embracing the skeptics, however. Watching the play in an “alt-truth” and “Make America Great Again” mediascape, it’s hard to digest Atkins’s gleeful recreation of 1950s UFO testimonies. Why offer audience members a look at mid-20th century rural American spectatorship of the skies, only to not interrogate the overwhelming whiteness and maleness of this gaze?

Nevertheless, We Are Not Alone is capable of nuanced political engagement. For myself, the show’s emotional highlight is not when he meets the self-proclaimed half-alien, half-human hybrid whose reassurance that “You are not alone” gives the show its title. Without a doubt, this crown jewel is reserved for Atkins’ recreation of his sitting in a conference room of women believers. Taking on their voices, he reproduces their tales of aliens leaving beheading scars on bodies and the miscarriages of half-alien babies. Such stories serve as an “alternative” history to gendered traumas. On a planet where female testimony receives little confirmation, this circle of belief in the unbelievable is successfully reproduced as a sincere and necessary reprieve. With tears in his eyes, Atkins says as much and relieves the audiences of his masculine narrative authority as he sits surrounded by empty chairs for the women who aren’t there. To the Powers That Be, and implied by the hollow staging, these ladies might as well stay invisible. Perhaps some mistrust, then, in mainstream outlets of “truth” is well-placed.

These moments of self-awareness only serve to exacerbate the show’s rough case of empathy whiplash, however. As Atkins twangs his way through a series of southern UFO-spotter impersonations, the stories often bleed too well into each other and homogenize the action into a big blob of quirk. Thankfully, the distinction between scenes is possible due to lighting designer Kimberley Purtell’s subtle yet impactful transitions, in addition to the rich sound design of Thomas Ryder Payne. Their combined work with space enables audiences to imagine all the many worlds of Atkins’ script within the smaller world of his simple stage.

We Are Not Alone aims to unburden “humanity” from belief in their own exceptionality, and it concludes on its titular mantra as one of kinship and liberation. Under a less talented performer, the closing monologue would land as condescending; Atkins’ chameleonic stage presence lets him slide easily from other bodies and back into his own, laying bare his own humanity, full of his own narrative uncertainties and flaws.

Yet who but the most privileged of earthlings, in 2019, needs to be taught that they aren’t the center of the universe? For the past century (or five), there have lived specific colors and creeds of people who have been well-probed by this “inferiority” theory. Such earthlings apparently fall outside of Atkins’ dramatic ethnographic selection, and such earthlings might find themselves underwhelmed by the scope of this not-so-universal exploration

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Christine H. Tran.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.