An interview with Andrii Palatnyi, Dakh Theatre / Gogolfest in Ukraine

This year, Dakh Theatre and its festival counterpart, Gogolfest (ETC members since 2015), have become digital pioneers.

Their experiments with streaming and Zoom theatre have expanded audiences all over the globe—even winning awards from the Ukrainian Book of Records.

What’s interesting is that they learned almost everything from scratch during the pandemic.

Limited digital experience

Speaking to ETC, Andrii Palatnyi (actor, producer and festival curator at Dakh Theatre) set out the context.

Dakh did have some experience with live streaming on site-specific work, but it was partner organizations that had taken care of the digital work.

They also had a digital strategy, developed in 2019 after Andrii visited ArsElectronica and the Academia Digitlitat workshop at Theatre Dortmund (with support from ETC for travel grants!).

But when the lockdown was imposed, and they had to cancel everything, Dakh was faced with three big issues:

- The impossibility of realizing artistic events

- The inability to reach audiences in person, and

- A lack of experience and skills in using modern technologies for implementing theatre projects.

“The world said to us: if you want to continue to do theatre, you need to use a new instrument.”

Phase One: Designing projects

So under the direction of Dakh founder Vlad Troitskyi, the company began a period of adaptation, from the middle of March until the beginning of October, in which they designed digital projects for the new, Zoom-focused reality.

“This was the period when we realised that we needed something new—a format, a model. I call it Phase One, where we created the digital laboratory and prototypes to test a different way of doing things.”

Convincing actors to work online

Much like we’ve heard from other theatres at ETC conferences and events, the actors were initially resistant to working online. It was a combination of two things that won them over: transparency, and a clear vision for the future.

“We are an institution which is not subsidised. It means that if we don’t do things, we die,” he said. “That’s why the conversation was very short. The story is very simple. We had a big strategy, lots of festivals, international collaboration, and then everything fell down. We didn’t have anything. That’s why we lost offices—we lost most of the team honestly. With the actors ready to stay, as a manager, I explained the way of thinking and what we were looking for. I said what we know, and what we don’t know. We don’t know how long this situation will be—is it months or one year? We don’t know if new projects will come. We don’t know about grants. There was a real period when everything was frozen. We said: we need to continue.”

Once they had actors and creatives ready to accept that the new projects would be high-risk, with money coming in later, they started adapting to the new environment. For the first two months, Andrii developed what he lovingly calls, “The School of the New Type of Acting.”

Zoom Acting: An Explainer (Talk w/ Andrii Palatnyi, Dakh Theatre)

Three digital projects

As part of the laboratory, they worked on three digital projects: Alambari, Zoomtime, and Book Tasting. This has been joined by later projects, like the dubstep-infused traditional Ukrainian opera, PhD Opera.

Alambari, which had 135 participants from 47 cities in 18 countries, was a project to showcase the ‘social digital rituals’ shared by people around the world. People joined Zoom meetings and did the same things at exactly the same time—looked into the camera, showed the sky, had a conversation with a loved one, made a cup of tea.

Book Tasting was a mixture between staged readings and analysis of literary texts, and Zoomtime was the conversion of a pre-existing offline show into an online format using Zoom meetings.

Live and digital at the same time

Andrii and the team have stuck to one very important rule: digital work is not the opposite of live performance. The two concepts are complementary and equally valid vehicles for creation and reaching audiences.

They made these messages clear in marketing material:

“It’s live acting, and live viewing. You know as an audience that we’re doing it now. It’s not a recorded thing. And you know it because you are together with us in the meeting. It means that it’s true theatre as I create a character in exactly the same moment as you in a conference. That’s why it’s important that you see it now. If you see it later, in YouTube, it will be a recorded version and it will be a completely different feeling for you.”

Three ways for thinking about digital work

In addition, Andrii developed a three-part way for thinking about digital activity.

1) An online adaptation for an offline product. This could be classical streaming of a show, or online acting

2) A digital-only product, built specifically to exist in a digital space

3) A digital product that is created with the express strategy for later bringing it offline.

“For me these are three different ways of thinking, but all of them work if you agree with the concept that offline-online is a synergy. All three of the prototypes could be split in the three boxes.”

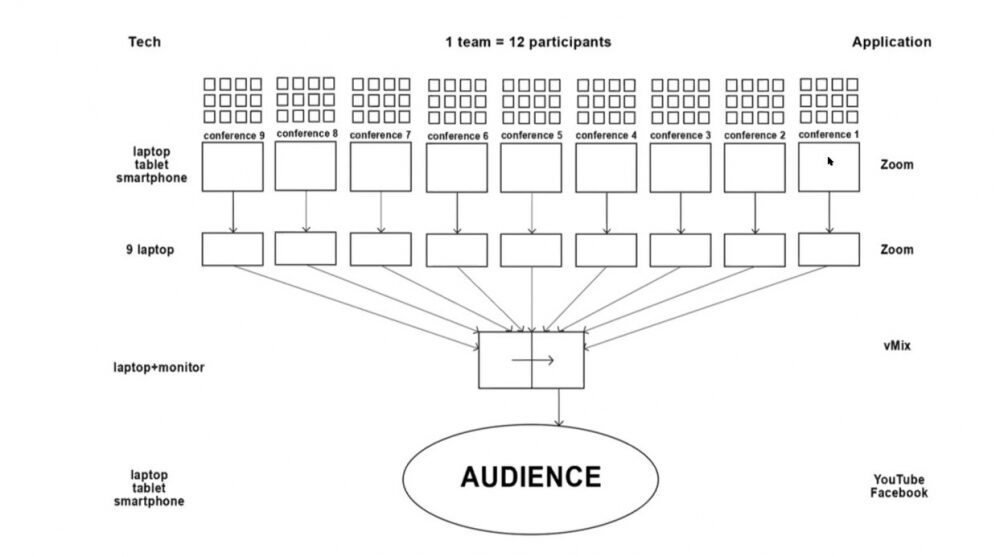

Alambari was done as a high-risk, live event, compiling multiple zoom screens into one and manipulating these in real-time.

“We did it with all risks. Sometimes, it didn’t work. But it was our decision to go with all possible risks, even if we didn’t know how to manage it.”

The program began with four screens, then six, and grew to 9 screens. ETC members can see more information about this process here.

They received an award from the Ukrainian Book of Records for the project, as recognizable as the first prominent digital event in Ukraine. “It’s an example of how things could go if you are working in the right direction,” he said.

Transformation into ‘offline’ products

One of the key pieces of learning was that projects could be transformed from a digital-only experience into an ‘offline’ one.

“We created a digital product during quarantine. But when lockdown was finished, we went offline with this project and created an offline installation. This is one of the ways that we think: we believe that projects can be transformed afterwards. It’s not like you’re online and that’s all, or only offline. With Alambari we built a moveable installation, which has visited four cities and different site-specific spaces.

“It’s an example of how we get from digital content to physical content.”

An adventure for audiences

The show was projected in various interesting ways—on the ceiling, on pillars of a 100-year old building. There was also a strong interactive component, with in-person audiences being able to stand in front of cameras and see themselves projected onto the walls alongside recorded content.

“It was also a laboratory of behaviour, to see how audiences interact between technology and art. [One audience member] intuitively took his gadget and started to act with it.

“This is also what I say: Digital is not only an adventure for theatre makers, it’s also an adventure for audiences.”

New ways to approach creative projects

Andrii says Alamabri changed the way Dakh will approach creative projects in the future.

“We understand now that we create cultural projects not only for Ukraine, but for an international audience. That was when we first really understood it.

“Second, the organisation of Alambari and communication gave us an understanding that it’s really a new period for collaborating with partners and structures. A lot of institutions agreed to participate in it. I can’t imagine an earlier situation when this would have been possible. I think it changed the industry relationship between theatre makers.

“And third is the way you create the ideas. It’s no longer just local topics: you start to think bigger and the frame of the world, what to talk about.

Testing prices for digital activity

For Zoomtime, which was a digital series, Andrii and the team tested a three-tiered pricing model, as part of the push to reach some sort of financial sustainability.

The first was simply access to a YouTube link, in which the audience was a passive viewer for a live performance. The second level was access to the Zoom meeting for one of the shows, after which the audience would be able to talk to the actors and the creative team, and the top-level—in effect a donation—was to buy access to all of the series in one go.

“At first we tried to put the same prices, a little lower, than usual prices in the theatre. But then we understood that we were wrong because you can’t expect people to pay the same price when they go physically to the theatre.” In the end, they priced one ticket the same as a cup of coffee.

There is a parallel story to be learned from Det Norske Teatret, an ETC member theatre based in Oslo, Norway. ETC members can read about their experiences launching the paid streaming platform, Direktstroyming, here.

Reaching new audiences

In marketing Zoomtime, Andrii realized that even without subtitling or working in a more ‘international’ language like English, they had access to a whole new international audience.

“Our audience, in this case, changed totally. We understand that it’s dramatic material. We act in Ukrainian and Russian. You could ask in this case: how international is it, if the performance was done in your native language?…But we also realized the product became interesting for Ukrainians living abroad. The diaspora. This is something we never expected. When you do theatre you’re normally reliant on physical audiences that you can reach. Here, we understood that all people that speak Russian and Ukrainian are potential audiences for this product. We had Ukrainians in Canada, Austria—people that know our activities but never see it physically. They had time, and they spent it with us on Zoom.”

The aim is to have a systematic connection with the diaspora, and this push for a bigger audience has changed the way the organization operates.

“When we create a dramatic digital performance, we know that people who speak this language are not limited only to the country’s borders. You create for a much bigger audience from the beginning and then think about how to reach them.”

He adds that this is very important in the multi-linguistic, European context—particularly during lockdown when you can’t really invite people anyway, and we need to think about how we rebuild communication strategies.

Phase Two: Digital Repertoire

Dakh’s digital repertoire is now increasingly established. From November to December 2020, they hosted 44 digital events, which consisted of:

- 4 new premieres, including the PhD digital opera, pictured above (7 events).

- 3 international streams of productions abroad

- 2 book ‘tastings’ (live animation and reading)

- 7 lectures in GOGOLAB

- 24 series of international digital residency

- 1 online flashmob

Closing thoughts

“This is a story about changing. We lost a lot. We lost all of our repertoire. I’d worked on it for several years—it was my blood, my energy, and I lost it on the first day of lockdown. But I was ready to accept this pain and immediately try to look forward because I think theatre, in general, is much more important. Theatre as a value for society. Theatre as one of the oldest technologies to create a world and analyze the world.”

Andrii Palatnyi is an actor, producer, and festival curator at Dakh Theatre / Gogolfest.

This article originally appeared on EuropeanTheatre.eu on January 15, 2021, and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Christy Romer.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.