“I meant to do something about it, but I didn’t.” So goes the refrain when we, as flawed human beings, are faced with politically- and emotionally charged strife: “I meant to do something about it, but I didn’t,” we say in retrospect, looking at issues of human rights and civil liberties. “I meant to do something about it, but I didn’t,” says Marla in Lauren Ferebee’s newest play, Goods, the technological repetition provided by her recording device a haunting thought.

For humanity hasn’t changed much by the year 2100, not in Ferebee’s world. Livable land may be rapidly depleting and refugees may be foisted into the starry sky, but humanity’s qualms and problems have not shifted, not really. This world premiere of Ferebee’s Kennedy Center-winning piece, presented by Chicago’s Artemisia Theatre, bills itself as simply a conversation surrounding sustainability. It is so much more. Following two intergalactic trash collectors as they come upon their 20-year work anniversary, Goods is an exploration of survival, selfishness, altruism, familial love, and the humanization and personalization of what we so quickly brush off as “not my problem,” as “objects,” as “goods.”

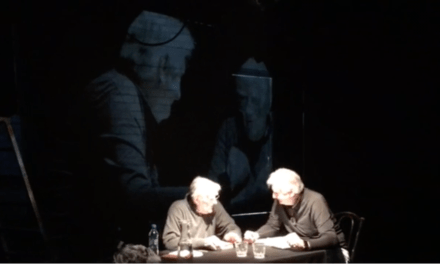

Considering how difficult remote green screen work can be, Artemisia does a wonderful job of communicating story and humanness within the confines of what we realistically know to be two separate rooms. Directed with the brilliantly light hand of E. Faye Butler, Goods is defined by the relationship between its two characters, an Odd Couple of sorts: Marla (Artemisia’s founder, Julie Proudfoot), a staid, paranoid older woman, seemingly representing right-wing conservatives; and Sam (Shariba Rivers), an outspoken, anxious adventurer, seemingly the show’s progressive parallel. The two have worked together for decades, and clearly “like each other enough to get the work done,” but could not have more polarized views. In one of the most obvious moments of conflict, Marla preaches the nativist view of “This land is our land,” adopted from her Border Patrol son, claiming a feeling of safety; Sam reproaches her with the query, “Who are you keeping it safe from?…It’s not about safety. It’s about [your] comfort versus [their] survival.” It is clearly a direct parallel to our contemporary world.

Parallels abound throughout the piece. Intergalactic “wait stations” are 2100’s version of keeping children in cages; young kids washing up on shore after their homes have fallen into the ocean is their version of the refugee crisis. Rising ocean and temperature levels have created a true international crisis, an image of what our world will become if we are not careful. Ferebee’s writing deftly navigates these parallels and moralistic lessons: nothing feels overly heavy-handed or like a soapbox monologue. Simply allowing the characters to live within their own opinion and life story gives Ferebee’s audience easeful, uncomfortable absorption.

Needless to say, though, Goods would not have worked without two actors skilled enough to take on a digital two-hander. It is in good hands with Proudfoot and Rivers. Rivers deserves special kudos: she remains grounded and genuine through every snap of Sam, an actor skilled in balancing the theatrical and the cinematic. Sam, in all her intricacies and mental struggles, becomes a vibrant, powerful character within Rivers’ expertise. She is truly luminous in this role. Rivers is well-matched with Proudfoot, whose acting style tends to float in the direction of cinematic Shakespearean, straight-forward and unwavering. The style variant is effective in showcasing this Odd Couple feel: at moments, I felt as if I were watching a classical actor and a contemporary actor attempt to find common ground, which, frankly, fits Marla and Sam to a T. Whether this was a fully intentional decision or not, it was a smart one. The audience immediately knows who these characters are as soon as the credits dissolve into the opening scene, even before the dialogue begins: Proudfoot sits tall and proud, lips in a stiff line, hands playing in a nervous tic; Sam’s feet are up on the hypothetical dash, slouched over, brows furrowed as she reads. Their individual personhood is made clear with immediacy.

The story and the actors that tell it are so engaging that it is easy to overlook minimal digital flaws. The green screen remains obvious the whole time, hands and faces occasionally disappearing into its abyss; several times, the visuals that Marla and Sam were supposed to be seeing in front of them appeared behind, instead. There are a few sound problems, too, balancing the actors’ voices with effects and dissolves; there were a few moments when the transitions were a bit too jarring for my taste, far louder than the dialogue preceding it. There arose several busywork questions, as well, largely surrounding drinks: if two gallons of water is $60, why are they constantly drinking coffee? And why does it take so long for the coffee to be finished? Is there actually anything in the kettle they’re pouring from, or is it just air?

These are small questions in the scheme of things, though. Largely, Artemisia’s production works well, green screen and sound issues and all. In fairness, I must mention the utilization of disembodied, staticky voices to represent PTSD and panic attacks: sound designer Willow James excelled in that facet, crafting aural experiences both disturbing and touching. For all the audio balance problems, that deserves a shoutout.

Goods is by far deserving of the praise coming its way. Ferebee’s skilled, compassionate pen, Proudfoot and Rivers’s grounding, Butler’s astute direction, and the editing of James and videographer Peter Sullivan combine to create a piece as uncomfortable as it is touching, as witty as it is heartfelt. In a world where cinematic staging has received a bad rap, this is an example of just how beautifully it can go.

Artemisia Theatre’s Goods, written by Lauren Ferebee, directed by E. Faye Butler, starring Julie Proudfoot and Shariba Rivers, and featuring costume design by LaVisa Williams, videography by Peter Sullivan, and sound design by Willow James, runs through May 30, 2021. For more information, and to obtain tickets, please click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Rhiannon Ling.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.