“I’m being pillaged and raped. I’m being pillaged and I’m being raped. And I don’t like it,” says Anna on the verge of a breakdown, her life spun into utter turmoil by the dangerous, spontaneous appearance of an emotionally damaged man. Oh — but in his musky brokenness she sees her own reflection, realizes her own damage. “Oh damnit all. Did he leave?” she asks, her words dripping with a tortured longing. In Burn This, Lanford Wilson’s 1987 play revived on Broadway this year and opening Tuesday night, this is the stuff of sultry, forbidden romance.

And when it’s all over, that romance risen and fallen, given in to temptation and flowered into love, she wilts into the arms of her precariously tortured lover, her life changed by the attractiveness of a man who destroys and therefore shapes what he wills, and sighs dreamily: “I don’t want this…Oh, Lord, I didn’t want this.”

I shouldn’t have to tell you that this is not the kind of romantic fuel which lights a warming fire on the stage today, or kindles any flame in which I’d want to see the lustrous reflections of burning passion flicker. Directed by Michael Mayer and starring Adam Driver and Keri Russell, Burn This is a perplexing choice as the first posthumous Broadway production of a playwright who has, in works like the Pulitzer Prize-winning Talley’s Folly, manifested the simple, translucent beauty of true romance.

But, Burn This, like its name, is a play of fire and fury, marred by the darkness of grief and the uncertainty of reckless living; set in 1987, the AIDS crisis (though not explicitly addressed) and the cocaine epidemic hang gravely over the bohemian lives of its artistic characters. Underneath it all, Wilson divines a romance between a man and a woman hanging perilously off the cliffs of grief and loss, at the edge of social convention — a love defined merely and only by mutual destruction.

The story is fairly straightforward. Anna (Keri Russell) is a dancer and choreographer, fiercely dedicated to her work, who lives with Larry (Brandon Uranowitz) and Robbie, two gay men. When Robbie, Anna’s close dancing collaborator, dies in an accident, Anna and Larry are surprised by the fiery, spontaneous arrival of Robbie’s brother, Pale, (Adam Driver) who’s come to the apartment drunk, coked-up, and hopelessly in grief to collect Robbie’s things. Anna and Pale, bound by mutual mourning — he, a homophobe, grieving a brother he cared little to know, she, her closest friend — are immediately drawn into a capricious, volatile romance. Pale, erratic and furious, struggling to live within the conventional lines of a demanding job and nuclear family, plummets willfully into Anna and Larry’s modern lifestyle, and Anna, though fearful of Pale’s unpredictability and loosely tied to her steady (by comparison) partner Burton (David Furr), is ultimately bewitched by the exhilaration of a broken man.

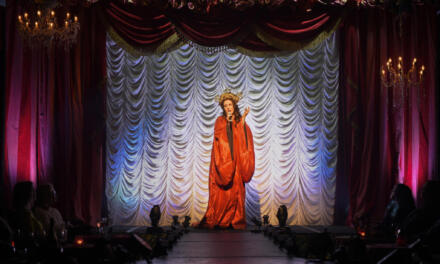

Michael Mayer’s revival wraps all this rage in a chic, neat and straightforward production that mines its explosive passion from a super-star cast, dripping with an appropriately modish swank for its mid-80s setting (costumed by Clint Ramos) and failing, inevitability, to fix the fatal flaws written into badly-aged characters.

“You have completely mastered half the art of conversation,” Anna says to Pale after she first meets him; the irony is that such a sentiment is also true for the structure of Wilson’s characters. Only the men in this play have any definition, and only they control Anna’s arc. Pale is a restaurant manager, neurotic and obsessive, and a homophobe prone to sudden and temperamental bursts of anger; he is destructively particular and manically controlling, but respectful and emotionally open to those he admires. We know some things about Larry, too. He works in advertising, is gay, Jewish, nearly a caricature, sexually adventurous (or, just lonely) and admirably loyal — a fixer. Even Burton, Anna’s lover, has dimension. He’s a talented screenwriter, passionate about the movie industry’s hypocrisy, born into substantial money, and hasn’t quite figured out his own sexuality or who he is outside of wealth.

Anna is a blank slate. She’s, well, a dancer, passionate about dancing who figures her emotional turmoil through dancing. We know nothing about who she is beyond her work with Robbie — and she doesn’t seem to know either. In Pale’s spontaneous and explosion intrusion her own emotional turmoil is reflected. His repeated arrival at her door, looking for sex and companionship, is what propels her plot. When mid-play she kicks him out for good, asserting her agency, she contradicts even her own desires, still in love. She cheats on Burton with Pale, but has not the emotional instrumentality to leave him; Burton closes the door behind him. While Pale rages, she stands, listens and has little to say. She is a barely realized character, defined only by the emotional heights of the men around her.

David Furr, Keri Russell, and Brandon Uranowitz in “Burn This.” Courtesy of Matthew Murphy.

And Keri Russell and Adam Driver, though they bring sexy, alluring star power to these flawed people, only seem to accentuate the issues of their characters’ composition.

Keri Russell is relatively green to stage acting, and her Anna is cool and collected, slight and sophisticated — believable, for sure, if not muted in the modernist way of charming impersonality. Very 80s. But it takes some time for Russell to warm up, and Anna only begins to feel like a breathing, flexible character half-way through the play. She’s easily mowed over by Adam Driver, ascended master of quirky, emotionally susceptible and anger-driven, fractured masculinity. Pale is a fairly similar paradox to Driver’s character of Adam in HBO’s Girls, and if you’ve seen the show, Pale feels awfully akin to Driver’s Adam. He flits from intense, laboriously human, emotional heights — from raging anger, to wailing, curdling screams of sorrow. His Pale is equal part hilarious and disturbing — perplexing always — and he holds the audience of the Hudson Theatre in the palm of his hand.

But I’m not sure what such bravado does for the play, already struggling with fatal imbalances between Pale and Anna. Whatever potent desire that broils between the two has Michael Mayer’s compelling, suspenseful stage direction to thank. With a directing record of shows like Spring Awakening, rich in story-telling through imaginative, physical tension, Mayer is a master of movement, of the choreography and careful, subtle dance of bodies on the stage. Anna and Pale move around one another, often physically in a counterpoint — standing at opposite ends of the stage, attached to either end of some carnal axel, slowly moving closer together as the play progresses. Mayer’s staging, armed with Derek McLane’s evocative scenic design of a mid-80s industrial loft — the sort of place you’d kill for or wouldn’t be caught dead in, Wilson instructs — is itself beautiful and self-consuming.

Only Brandon Uranowitz (curiously in his first role playing a gay actor in a Broadway play) as Larry hits a believable stride among his onstage peers, elevating his character above caricature — that gay, Jewish realist, plagued by sexual angst and urban neurosis ever a frequent archetype in plays of this era — and toward an important, integral personification of the fibers of a changing and modern gay life in the 1980s.

And, in fact, if anything is successful in this play it’s the messy, entangling seduction of that evolving social fabric. If Burn This is the story of a blazing, mercurial romance in the 1980s, then also is it an exploration of the singed, fraying nerves of the 20th century, bound for self-destruction in the urban gray of the late 1980s and daily in the process of re-negotiation into a distinct, modern identity. Anna lives (or lived) with two open gay men. Larry is unapologetically flamboyant, often goading Burton and Pale to indulge his desires. Anna and Burton embody the casual, open archetype of modern romance — in this iteration nearly a prototype of what is to come. Pale is the chewed-up image of what normative social life can do to someone who doesn’t fit within those restrictive boundaries, falling helplessly out of traditional life, inverting the illusion of artistic, urban elitism to find that they’re broken, too “What assholes. I thought you people was supposed to be with it, you’re supposed to swing, you know what’s coming down,” Pale agonizes.

These are the frayed ends of social life in the 20th century, ready to reborn into American modernity. Burn this — burn them, Mayer might implore us to do today — and make something new.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Michael Appler.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.