Avataar, staged by Nireeksha Women’s Theatre, delves into a virtual world of shifting identities, trivialized emotions and inane conversations.

However hard she tries, the woman finds it impossible to get to her past to rebuild her lost identity. Did she ever have one, she wonders.

History is replete with tales of domination and conquests, but all of men’s. About women, it remains strangely silent. Desperate she returns and loses herself in a virtual world, frenziedly swapping profiles and sifting through chat rooms to see whether she could catch a whiff of her essence, perhaps scattered and caught inside those meaningless chats in social media.

The eternal search continues…

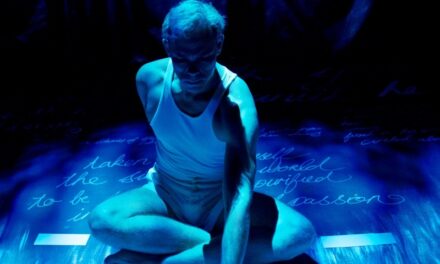

Nireeksha Women’s Theatre’s new play Avataar, which was staged at Vyloppilly Samskriti Bhavan in the capital city last week, is a searing exploration of the identity of woman and relationships in the virtual world – its razor-thin affairs, soulless social media posts, floating profiles, shifting identities – that has made a dent in the real world too.

The loneliness to which the hero Navin is condemned to, as he works on an oil rig abroad with the ‘weight of the blue’ inconsolably eating into his thoughts and dreams, represents the plight of all men who try to reach out from their island selves. His only contact with the mainland is occasional chats with his lover, Siji. He skims the surface of that relationship, never wanting to go beyond what he gets from Siji’s profile page. Her social media posts dripping with love, which are all poetic quotes Siji has lifted from elsewhere, were enough for Navin to project on to her an image of an ideal lover who could ease his sufferings.

A real woman with her own wishes would probably have terrified him. After all, only projections, reflections and echoes matter in social media.

The fragile world would have held on if the real woman had not shaken off the chimera and announced that she wanted to get real – a grave sin that shatters the glass walls of social media etiquette.

The defaulter must suffer.

The viewers follow the agonies of Siji who now sets out to find her past, her lost identity. Her last name Kottoor might have taken her to the house where she was born, but Siji realizes, that such real places, soaked in the earthy odours of soil and blood that lie unmapped by search engines, have long lost their moorings and drifted away to unreachable distances, a grim pointer to the future. She must once again get back to the virtual world, from where she began, for the search to continue.

Meanwhile, the heroine finds in Deepa, her online friend, a woman who has learned the skill of living in the new world. Love can exist only if there is a distance between the participants, Siji learns from her, and virtual media offers that aloofness. Come close only at the risk of falling apart. “Three minutes,” she tells Siji, with the pain of her experiences thrumming behind the sarcasm, “three minutes is all it takes for any relation between man and woman to decide between bed and violence.” Deepa has already seen enough violence in her life.

Whenever the viewer loses his bearing in the ever-shifting dunes of the virtual world, the character Troll weaves into the story on roller skates, with his scathing but enlightening comments. His uneasy questions can either be dodged or confronted head on. But don’t think he offers any resolution.

E. Rajarajeswari’s brilliant script etches the life of a woman, any woman, her search for identity and her frustrations in the virtual world. Men are not portrayed in a bleak, one-sided light; they also get caught in the roiling waves of fast-shuffling identities of the virtual world. Yet, at least, they have an identity and a history of conquests to fall back on. For a woman, it is a post-modern play of surfaces, without any roots or essence.

“It took nearly five years for this story to evolve,” says Rajarajeswari. To find visual tropes to a story that deals with the virtual world, where all action revolves around social media chats, is a tall order for any director. Here is where Sudhi Devayani excels. “The theme was challenging, and its resonances were many,” says Sudhi.

“The decision to bring in the trampoline as a platform was a key moment during our research. Everything else suddenly fell into place.” In the play, whenever tension mounts we see the characters go bouncing on the trampoline. “It requires immense balance and skill to stay afloat in the virtual world,” Rajarajeswari says.

Aswathy Chand Kishore’s Siji and Sarat Sabha’s Navin sizzle as the main characters.

Prasoon V.T., Biresh Krishnan, Molamma K and Neena Gireesh also put in good performances. Brilliant scenography and subtle lighting by Shibu S. Kottaram takes the play to another sublime level.

This article was originally published on the TheHindu.com. Reposted with permission. Read the original article.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Manu Remakant.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.