Without an audience in the theatre, there’d be no drama. But audiences have been providing rather too much drama in UK theatres–if a couple of recent articles in the industry bible, The Stage, are anything to go by.

Eating can be noisy and distracting for the cast–especially when it comes to unwrapping boiled sweets and the like. According to theatre owner Nica Burns, when it comes to stopping people eating snacks during a performance altogether, the horse has bolted. But she told The Stage that there are limits (one audience member apparently tried to get away with bringing in takeaway pizza). Her company has been experimenting with non-intrusive packaging.

“A few of the very noisy packages have now been gracefully retired, and we’ve brought in similar ones that don’t make any noise,” she said, adding: “It’s a work in progress.”

More contentious by far is the use of mobile phones during performances. A theatergoer at the Old Vic was recently punched by the partner of a woman using a mobile phone throughout the first act after he remonstrated with them. Theatre critic Mark Shenton pointed out (also in The Stage) that in New York, since a city ordinance of 2013, mobile phone use is illegal–and urged UK theatres to consider doing the same.

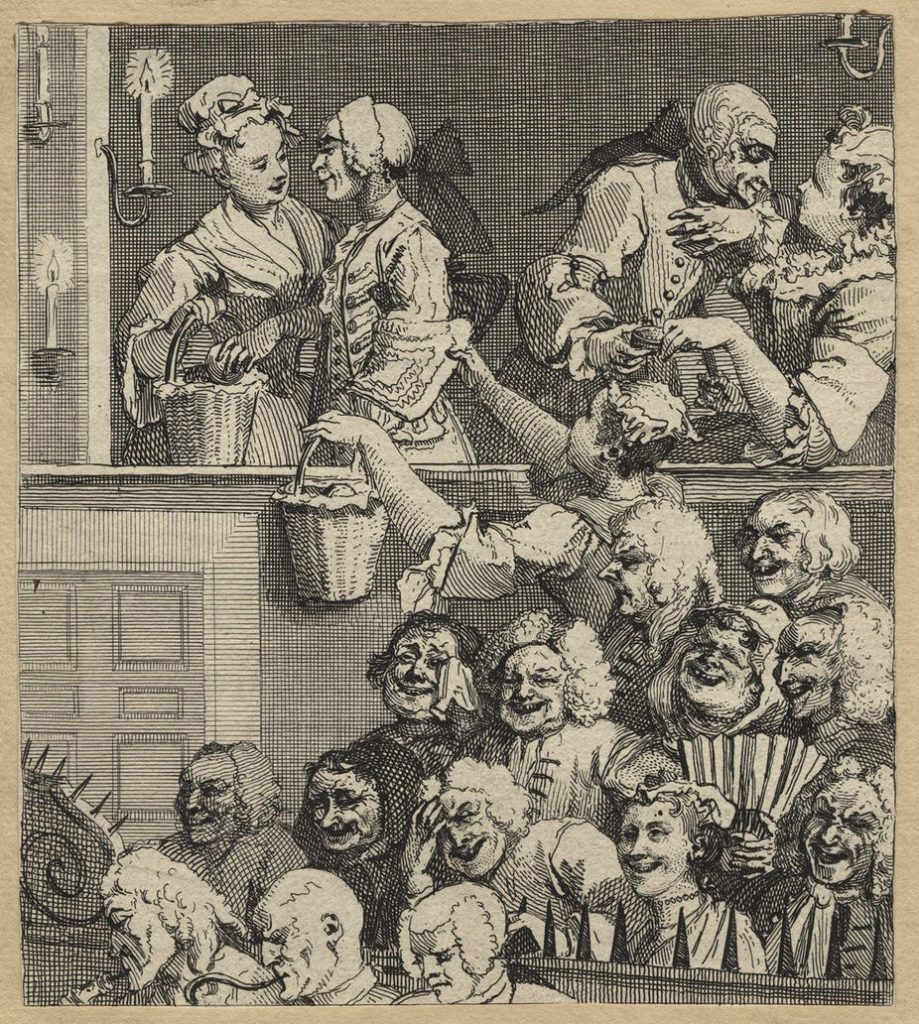

The Laughing Audience (or A Pleased Audience), by William Hogarth. National Portrait Gallery

But worse things have happened. In 2015, a man in the audience at the Tony Award-nominated play Hand To God on Broadway climbed on stage and attempted to charge his mobile phone by plugging it into a prop plug socket on the set. On another occasion, actors Tamsin Greig and Haydn Gwynne, stars of Women On The Verge Of A Nervous Breakdown had to intervene to stop a couple apparently having sex in the audience.

Oi, you in the cheap seats

What are things coming to? As it happens, the concept of a quiet, polite and well-behaved audience is rather a modern phenomenon in Britain (as it is in America). Charles II restored the English stage in 1660–after it had been banned by Oliver Cromwell during the Protectorate–and from then on, theatre audiences were anything but quiet and polite, expressing their opinions, vocally and physically, on the production and on the performers. And what took place on stage was not exactly designed to promote quiet.

Nell Gwynn, Charles II’s favourite actress.

Gerard Valck, via National Portrait Gallery

These were licentious times–theatre auditoriums were also used for the commercial exchange between client and prostitute. In 1698, Bishop Jeremy Collier was outraged by such activities and published a monograph on the topic –A Short View Of The Immorality And Profaneness Of The English Stage, making a serious accusation against the theatre–which included mocking the Bible and lewdness. For the first time on English stages, women were permitted to act in productions, causing scandal by sometimes displaying a promiscuous and provocative leg in what became known as “breeches roles.” The most famous breeches star of the era was former orange seller Nell Gwynn (or Gwyn, Gwynne) who parlayed her popularity as the leading commedienne of her age into a more lucrative role as the mistress of King Charles II.

The boisterousness of the theatre as well as its potential subversiveness (mocking the Bible was frequently accompanied by satires against the government of the day) led to the Theatre Licencing Act of 1737, which stipulated that all scripts had to be vetted by the Lord Chamberlain and only two theatres, Drury Lane and Covent Garden, which operated under Royal Patent, could stage spoken dramas.

Nuts and other criticism

While the two patent theatres established a degree of control over audience behaviour, it would be several decades before British audiences would become relatively silent witnesses in the auditoria. Charles Dickens satirised theatre’s noisy atmosphere in Great Expectations (1860/1861), exposing amateur “roscian” Mr. Wopsle to the taunting humour of the “debating society” in the gallery, whose “general indignation” at the performance took “the form of nuts.” The throwing of food, among other choice objects, was a risk that actors frequently faced. Dickens’ satire here is aimed at poor performances as much as the audience in the cheap seats (at this time, housed in the gallery).

Mr. Wopsle as Hamlet, from Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations. Harry Furniss

The Theatre Regulation Act of 1843 disaggregated the power of the Royal Patent theatre houses, and other theatres were permitted to stage serious drama, which coincided with a change in approach by theatre owners and managers, whose focus became increasingly fixed on attracting a wider audience through their doors. Styles of auditoria with more open spaces and better viewing were designed to attract a wealthier (and therefore assumed to be less rowdy) audience. But, by the mid-19th century, the concept of theatre had changed. Instead of being seen a potentially riotous assembly, it was increasingly viewed as a potential harbinger of aesthetic integrity. Ultimately Dickens’ caricature of theatre audiences was ideologically constructed and he consolidated a mythology that it was the working classes (a diverse group that included seasoned and serious theatergoers) that brought noisy disruption to theatres.

Additionally, by the mid-19th century, capaciously emotive and sometimes explosive melodramas–with scenes of danger, derring-do, and despair–held sway across major theatres. Featuring heroes and heroines, these productions appealed to audience sympathies from across a spectrum of economic positions and class groups. Any sound in the auditoria at this point was as likely to be sweeping approbation as discontent.

Through a combination of these and other factors, a system of regulation emerged around audience behavior, and though we think audiences are or should be quieter than they were, reports of displeasure expressed in the auditoria have continued throughout the 20th and into the 21st centuries.

![]() So, this current disruptive use of mobile phones is the latest in a long line of audience misbehavior. We can never know what inspires our fellow playgoers to engage in potentially disruptive activity–but we know for certain that it has always happened and, likely, will continue to do so.

So, this current disruptive use of mobile phones is the latest in a long line of audience misbehavior. We can never know what inspires our fellow playgoers to engage in potentially disruptive activity–but we know for certain that it has always happened and, likely, will continue to do so.

Advertising card for The Streets of London, Princess Theatre, 1864.

This post originally appeared in The Conversation on December 20, 2017, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Theresa Saxon.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.