Akhmatova. Poema Bez Geroia (Akhmatova. Poem Without A Hero) has been nominated for a 2017 Golden Mask award and is the third in a set of five plays in the Zvezda (“Star”) series at Moscow’s Gogol Center. The Zvezda project, announced by Kirill Serebrennikov in February 2016, features theatrical productions built around key works by some of the most important Russian poets of the 20th century: Pasternak, Mandelshtam, Akhmatova, Kuzmin, and Mayakovsky. The project, which spans the 2016-2017 seasons, includes Pasternak. My Sister Life, directed by Maksim Didenko and featuring Veniamin Smekhov as one of the actors who plays Pasternak; Anton Adasinskii’s Mandelshtam. The Wolfhound Age, featuring actress Chulpan Khamatova; and Kuzmin. Trout Breaks The Ice, directed by Vladislav Nastavshev. (Serebrennikov is supposed to direct the premiere of Mayakovsky. I Love in late 2017, although the fate of this production is unclear, given that the director is currently under house arrest and facing charges of embezzlement, accusations that many believe to be fabricated.)

Anna Akhmatova’s Poema Bez Geroia (Poem Without A Hero) is widely regarded as the poet’s most cryptic and enigmatic work. The long, polyphonic text was written over the course of two decades and is a poem that, perhaps more than any of Akhmatova’s other texts, resists interpretation. The Poema is structurally and thematically complex, a textual space haunted by the specters of a range of cultural figures, contemporaries of Akhmatova who were caught in the whirlwind of tragedy and tumult of what the poet refers to as the “Real Twentieth Century.” And yet in the hands of the inimitable Alla Demidova, together with co-director Kirill Serebrennikov, its staging at Gogol Center is a production that is enchanting and exhilarating and that offers a means for audiences of today to connect to the spirit and force of Akhmatova’s literary texts.

Akhmatova’s Poema Bez Geroia is a work of poetry, but it has strong performative roots; Akhmatova at one time conceived the work as part of a libretto for a ballet, and the text has aesthetic links to Meyerholdian theatre. (Indeed, Meyerhold’s photograph is a key image in the video art that so enriches this performance.) Despite these theatrical roots, it is a text that has rarely been staged in any way. Demidova, the director and leading actress for the production, was entrusted with the work of editing and performing Akhmatova’s Poema, but in fact, her performance draws heavily on other texts, weaving together sections of Poema with the poet’s more well-known poem, Requiem, and three additional lyrics from the collection Northern Elegies, including a poem on the nature of personal and historical memory, “Est’ tri epokhi u vospominanij” (“There are three epochs to our memories…”).

Demidova is to Akhmatova what Alisa Freindlikh is to Tsvetaeva: a theatrical reader who perhaps best interprets and conveys the spirit of a poet whose works she so often performs in concerts and staged readings. Demidova has said we should not see her as playing the role of Akhmatova so much as conveying the poet’s story by means of the poetic word. At the same time, she admits that, “when you know someone very well and you tell their story, you unwittingly begin to speak in their voice.” The vision for a fully embodied theatrical production of Poema started for Demidova in the 1970s, when she was part of an attempt to stage it with Dmitry Pokrovsky’s ensemble in Leningrad. The production never came to fruition (“It was too soon, people were not ready to hear Poema,” she writes in her book’s introduction), but she went on to perform staged recitations of Akhmatova’s works throughout her long and successful acting career. The year 2004 even saw the publication of Demidova’s book of commentaries to Poema Bez Geroia, entitled Akhmatovskie Zerkala (Akhmatova’s Mirrors). While this scholarly work was instrumental in deepening Demidova’s connection with the text, the staged production is not meant to explicate the text so much to provide a means of illuminating the work and to frame it within Akhmatova’s larger creative oeuvre during her mature period. As she explains in her book, Demidova is more interested in capturing the spirit of the times and helping a new generation of young people engage with the text on their own terms: “In Poema individual figures are not as important as the ‘aroma of the age.’ After all, in Poema, more than anything else there is a huge swath of the culture of the epoch, which for many of today’s young people has already become the distant past.”

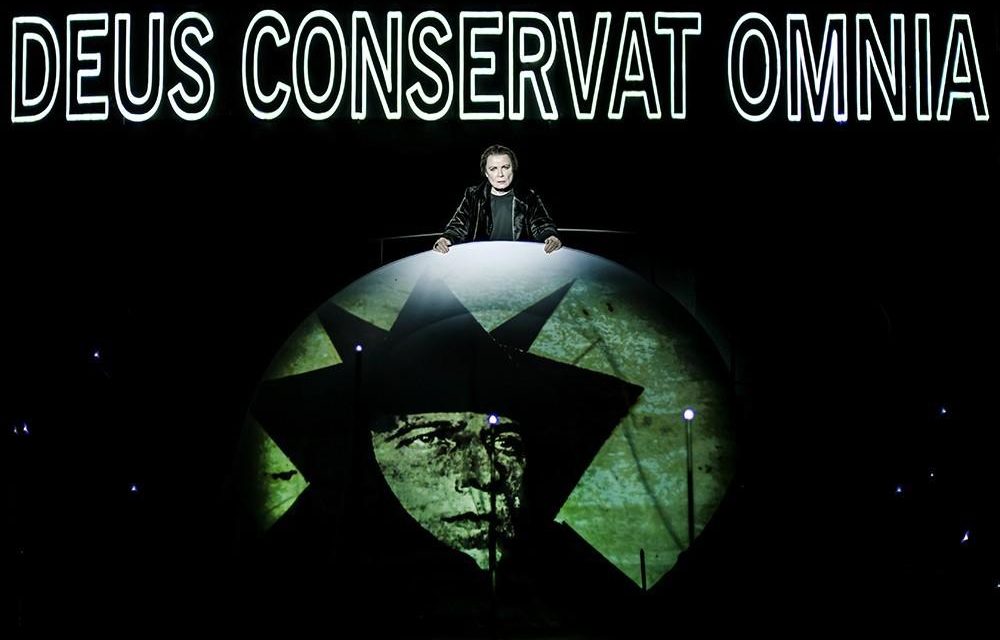

Emblazoned in lights above the stage when audiences enter the performance space is the Latin phrase Deus Conservat Omnia (God Preserves Everything). The Deus Conservat Omnia inscription—also the epigraph to Akhmatova’s Poema Bez Geroia—serves as a point of departure for the prologue to the production, a documentary prose monologue on the theme of loss and recovery that links the Latin phrase to two locations of significance in Akhmatova’s life and death in Leningrad. As she almost imperceptibly glides across the front of the stage, Demidova tells the story of Akhmatova’s death, of how Deus Conservat Omnia was inscribed not only on the Fountain House where the poet lived for many years but also on the Sheremetev Palace, the site of the hospital where her body was taken after she passed away. Demidova’s monologue also links the phrase to the story of documentary film footage of Akhmatova’s funeral that was widely believed to have been lost; Demidova happened to view the footage only much later, on television, while visiting the United States at the invitation of Joseph Brodsky. And so this prologue concludes with a mystical confirmation of “God preserves everything” in the context of the late 20th century. More broadly, of course, the Deus Conservat Omnia epigraph speaks to a larger faith in the power of the poetic word to bear witness to and endure amid the tragedies and tumult of Russia’s 20th century.

The subsequent sections of the performance take us through much of the text of Poema Bez Geroia, with its mirroring and masks, the shadows of dead poets, and the relationship of the ballerina Olga Glebova-Sudeikina and the spurned young poet Kniazev, who committed suicide in 1913. Kniazev’s tragedy is a key part of the opening of Poema and a troubling event for Akhmatova’s circle of friends in the immediate pre-WWI, pre-Revolutionary period. The next act of Demidova’s performance takes up the Poema’s concern with the spirit of tragedy in Russia’s “Real Twentieth Century.” The production features at its center a stunning work of video art by Aleksandr Zhitomirskii. A montage of the heroes of Poema flashes before our eyes: animated photographs of Blok, Meyerhold, Mandelshtam, Mayakovsky, and Esenin, as well as iconic images of Leningrad and of war. The visuals are accompanied by a powerful score by the talented young composer and musician Aleksander Boldachev, who, together with sound technician Daniil Zhuravlev, accompanies the more lyrical sections of the production with haunting atmospheric music for amplified harp, gusli, mouth harp, and piano.

The set design is minimalist, with vertical metal rods downstage standing in for funeral candles and a double staircase encircling a large circular disk. The disk is shrouded in a white cloth at the opening as if it is a mirror covered over for a funeral. Images are projected on this surface, and the shroud is later removed, revealing a large circular mirror—a dark, black hole of an image, used to great effect by supporting actress Svetlana Mamresheva, who plays a series of haunting female figures—Columbine, the ballerina Glebova-Sudeikina, shadows of Akhmatova’s former self, and the specter of death—that accompany Demidova’s commanding performance.

While the first act following the prologue centers on the text of Poema Bez Geroia, much of the remainder of the play, which thematically examines the experience of the Gulag and wartime Leningrad, is dominated by Requiem, Akhmatova’s poetic testament to the horror of prison lines and the experience of mothers whose sons and husbands—like Akhmatova’s own—were imprisoned in the camps. The performance closes with Akhmatova’s famous lines, echoing the poetry of Horace and Pushkin on the exegi monumentum theme, about the creation of an enduring monument that would attest to earthly suffering:

If someday in this country they decide

To raise a monument to me,I give my consent to this ceremony

But only on one condition: do not build itBy the sea where I was born,

I have severed my last ties with the sea;Nor in the Tsar’s Village by the hallowed stump

Where an inconsolable shadow looks for me;But here where I stood for three hundred hours

And where they did not open the bolt for me.For even in blissful death I fear

That I will forget the Black Marias,Forget how hatefully the door slammed

And an old woman howled like a wounded beast.May the thawing ice flow like tears

From my immovable bronze eyelidsAnd let the prison dove coo in the distance

While ships sail quietly along the river.*

These closing lines bring the Deus Conservat Omnia theme full circle, as we witness how Demidova’s own work exists as a living testament to the remembrance of suffering and tragedy that Akhmatova fought to preserve.

In drawing so heavily in its second half on Requiem, the production perhaps doesn’t take Poema Bez Geroia to its full theatrical potential. However, in weaving so much of this more accessible—and certainly equally important—narrative into the play, Akhmatova. Poem Without A Hero becomes a production more digestible for contemporary viewers. In this way, it fulfills its mission to bring the story of Akhmatova, indeed of the whole of Russia’s “Real Twentieth Century” of tragedy and triumph of the human spirit, into the consciousness of a new generation of audiences.

*Author’s translation

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Molly T. Blasing.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.