Mark Bly

Mark Bly is an American dramaturg, editor, and lecturer. He was the chair of the MFA Playwriting Program at the Yale School of Drama from 1992-2004 while being the associate artistic director at the Yale Rep. He taught dramaturgy at Yale and was the director of the MFA Playwriting Program at Hunter College from 2011-2013, and subsequently the MFA Playwriting Program at Fordham/Primary Stages. Over the past forty years, he has served as a dramaturg, director of new play development, and associate artistic director at venues such as the Arena Stage, the Alley Theatre, the Acting Company, the Guthrie Theater, the San Diego Rep, the Seattle Rep, the Yale Rep and on Broadway, dramaturging and producing over three hundred plays. In 1985, he became the first dramaturg to be credited on a Broadway production when he worked on Execution of Justice written and directed by Emily Mann. Bly has been the dramaturg for the world premieres of plays by Rajiv Joseph, Suzan-Lori Parks, Tim Blake Nelson, Sarah Ruhl, Jeffrey Hatcher, Kenneth Lin, and Moisés Kaufman. He is the Script Consultant for the new film Ecstasy by the Brazilian screenwriter and director Moara Passoni nominated for an Oscar for the political documentary Edge of Democracy (2019). Bly has written for Yale’sTheatre Magazine as contributing editor and advisory editor, Theatre Forum, American Theatre, LMDA Review, and contributed to Dramaturgy in American Theater: A Sourcebook (1996), Between the Lines: The Process of Dramaturgy (2002), and The Routledge Companion to Dramaturgy (2014). He is the editor of the still in print Production Notebooks: Theatre in Process (Vol I. 1996, Vol. II. 2001). In 2010 Bly received the Literary Managers and Dramaturgs of the Americas’ G.E. Lessing for Career Achievement Award. He established the Bly Literary Managers and Dramaturgs of the Americas Creative Capacity Grant and Fellowship Award to support projects that advance the practice of dramaturgy in innovative ways to other disciplines. In 2019 Bly was the recipient of The Kennedy Center Medallion of Excellence for his lifetime work in dramaturgy and playwriting.

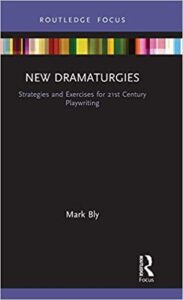

Mary Davies: Your latest book, New Dramaturgies: Strategies and Exercises for 21st Century Playwriting, published in 2019, is part of a series by Routledge titled Focus on Dramaturgy, edited by Magda Romanska. Where did the initial idea to write this book emerge from?

Mary Davies: Your latest book, New Dramaturgies: Strategies and Exercises for 21st Century Playwriting, published in 2019, is part of a series by Routledge titled Focus on Dramaturgy, edited by Magda Romanska. Where did the initial idea to write this book emerge from?

Mark Bly: It emerged largely from one source. It came from discovering the health of a long-time friend, María Irene Fornés (playwright, director), was declining. This news triggered many memories– my artistic collaborations with her as a dramaturg, but most directly her visitations to the Yale School of Drama, and the invaluable workshops she did with the playwrights when I was running the graduate program there. Irene helped me to understand the value of playwriting exercises. She did not offer prescriptive, diagnostic advice on the plays, but she helped the playwrights rediscover their voices in ways that I had never encountered before. The memory of her, the echo of her words, and the conduct of her life are in many ways the origins and inspiration for this book.

MD: How was the process of deciding which exercises to include in the book?

MB: I wish I could say it had been simple. I have created many exercises over the past 25 years for gifted writers from The Kennedy Center, the Yale School of Drama, the University of California San Diego, the University of Texas at Austin, Hunter College, Fordham/Primary Stages, Columbia University, NYU, and the University of Iowa, to name a few. Many exercises emerged from a direct response to playwrights’ needs in the moment. They were in response to some existing crisis, either in an individual playwright’s writing, a writing community that I was working with then, or to expand a writer’s voice. When I committed to writing the book, I was drawn to exercises that had generated scenes or new plays time and again and have continued to matter. That was my starting point for making a decision. There are exercises such as “Einstein’s Dream Exercise”, “The Kafka’s Train Exercise” or “The Sensory Writing Exercise” by me that are 15-25 years old. Yet they remain inventive, vital and alive. For example, Sunil Kuruvilla, whose work has been performed at the Yale Rep and Stratford Ontario Canada, wrote Minus 1 in response to “The Sensory Writing Exercise.” In his commentary for my book, Sunil shared, “Years later, I love this exercise… And when writing, I try to use all the senses… Mark’s instructions to write from the inside, not the outside, always lead to discoveries. Tom, a character in the play Minus 1, makes an observation in his logbook that ‘people don’t always have to be smaller than their imagination.’ This exercise still helps me write larger than I otherwise would.”[1]

I always wanted my exercises to create surprise, with challenging limitations, and shifting unexpected perspectives: ones that ask, “What if?”. Just when the writers felt they had nothing more to say, felt trapped or lost, these sparked a new story within them or helped them think about what they were working on in a new, unexpected way.

The writers I have worked with realized that “The Kafka’s Train Exercise” is such an exercise. It has generated over 250-300 short scenes and plays alone at The Kennedy Center. There is something unique about it. Writers encounter the exercise and initially think it is a ‘throwaway’, filled with limitations and parameters, but they go away and realize it is deeper. It always mysteriously connects to the plays they are working on or triggers a new play that has nothing to do with a train or Kafka. They discover that limitations can surprisingly trigger creativity. Lindsey Ferrentino, whose play Ugly Lies the BoneI ‘ghost dramaturged’ before it was first produced at Fordham University (2014), then at Roundabout Theatre Company (2015), and later at The National Theatre (2017) in London, described her response to my “Kafka’s Train” exercise and its impact: “I remember the “Kafka’s Train Exercise” in particular because of the lengthy eight-step list of requirements for the scene, which at first glance seems overwhelming. But in focusing on these rules, and on something else aside from your own writer’s block, inadequacy, or fear of writing poorly, you have no other choice but to write.”

MD: Not only does your book include your ideas on playwriting, but it also contains lively commentary and short plays or scenes from former students of yours who have gone on to the prominent stage and television careers. What is so beneficial about hearing their perspective?

MB: There are many playwriting books, but I wanted to offer unique elements typically not found in them. In each of the nine chapters, I share the origin of the exercise – why and how it came to be – along with supplementary reading, and visual art that create a context for the exercise. But what makes this book unique is the “commentary”, stories by the playwrights on when they first encountered the exercise, how it continues to have a major impact on their writing today, followed by the original scenes and short plays the exercises first generated. This is rare in playwriting texts. These multiple perspectives and a demonstration of one outcome of the exercise by a playwright are beneficial. The book is our book, not simply my book.

MD: Some playwrights in the book share they developed their responses into a full-length play, but what happens if the writing generated in response to an exercise doesn’t progress beyond a scene?

MB: The exercises are there to address a crisis during the writer’s process or to expand the writer’s voice. The writer’s response at first may only be a scene. It may when read be judged “minor” by others but the writer knows something we do not know; a character in it will solve something, may move into another play and become a major character there or be the seeds, or engine, of a new play. Or, these exercises can become ‘tools’ for the writer to store away in their playwright’s toolkit to solve future playwriting mysteries. I included Marcus Gardley’s commentary and a scene he had written in response to the “Character’s Greatest Pleasure Exercise,” at a time when he was writing the third part of a trilogy on the migration of Black Seminoles from Florida to Oklahoma. He deployed the exercise to help unlock a key scene in the play, but equally important, Marcus learned to trust the exercise as he mentions in his commentary: “…if I ever experienced writer’s block or if I lost sight of my focus, I always had a way back in through the exercise of pleasure. It’s like losing your way in the woods and finding your way back home through your own unconscious”.

Early on I decided I would depart from the existing model of sharing only scenes written in past workshops. For one chapter I commissioned former student Ken Lin, known for House of Cards (HBO), Warrior (HBO), and Kleptocracy, to write a new response to the “Nashville Film Exercise,” through a lens he had acquired as a writer for both the stage and other media. His commentary at a distance of 15 years from first doing the exercise and then revisiting it is revelatory: “I have not done a writing exercise in a long time, and since writing this scene, I’m resolved to make exercise-writing a part of my process. Once you start working in the world, and your projects begin to have many masters (in the form of commissions and assignments), characters and stories can languish in the mind while you focus on other responsibilities. This creates a certain kind of artistic tension that can steal focus and creative energy… When that happens, the impulse gets suspended in a way. It was very useful to just get something out on the page here to release that creative energy.”

MD: Your book “offers dramaturgical strategies and tools for confronting and overcoming obstacles that all playwrights face.” Can this book be utilized by actors and directors too?

MB: It has been thrilling for me to discover the growing range in which these exercises have been deployed. I learned recently that my “Character’s Greatest Fear Exercise,” or a variation on it, was being used by former students for shows such as Hell on Wheels (AMC) and NOS4A2 (AMC). This makes perfect sense because when I spoke to the playwrights about this exercise or “The Character’s Greatest Pleasure Exercise”, I always talked about it in relation to the character’s secrets, actor’s challenges, and the pressures the character is feeling. When that pressure explodes to the surface, it can drive the momentum of the play forward. These are important issues for directors, actors and showrunners to grapple with in the work, so, naturally, these exercises can be invaluable tools.

Perhaps the best example of how the exercises can be utilized by actors and directors is shared by Moisés Kaufman, the founder of the Tectonic Theater Project and co-creator of the revolutionary devising process Moment Work. Molly Smith, the Artistic Director of the Arena Stage of Washington D.C. where I worked, was chosen to do the world premiere of 33 Variations by Moisés. 33 Variations explored why Beethoven, became obsessed with a ‘cobbler’s patch’ of a waltz, and instead of composing a single waltz in response to a commission by a Viennese publisher, he created thirty-three variations. For nearly five years, I worked beside Moisés as his dramaturg, integrating Tectonic Theater Project’s Moment Work, actor and design work, and my exercises wherever possible. We ached to know this mystery of Beethoven’s 33 Variations as we did over 15 weeks of rigorous workshops, East and West Coast premieres, and finally a Broadway production. In his Foreword to my book, Moisés shares that he and his company had immersed themselves in Beethoven research and interviews with experts. These were all deployed in rehearsal toward their Moment Work. In rehearsals, however, they hit a “roadblock” and all the research and ideas were overwhelming, and not easily translated for the stage.

It was my exercises, recollects Moisés in the Foreword, that broke up the “roadblock”: “As the dramaturg of the play, Mark asked questions, questioned our assumptions, and gave us exercises to discover the truth at the heart of the play […] Because of his inquiries and exercises, the characters became richer and deeper, the story more thrilling, and the ideas at the core of the play more clearly articulated.”

The Moment Work, because it seeks to reinvent the way plays are made, is a natural partner to my exercises and I have been lucky to continue to work with Moisés’s Company over the years as a dramaturg.

Mary Davies is a Ph.D. student co-supervised by the Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC) and the Shakespeare Institute, University of Birmingham. Her current research focuses on the intentions behind the 2016 re-opening of The Other Place (TOP), the RSC’s studio theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon. Mary is also a dramaturg and was the 2018 Early Career Dramaturgs’ Representative on the Executive Committee of the Dramaturgs’ Network. Mary was awarded a Master of Arts degree in Text and Performance from the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art and Birkbeck College, University of London.

[1]All quotations by Sunil Kuruvilla, Lindsey Ferrentino, Sarah Treem, Rolin Jones, Marcus Gardley, Ken Lin, and Moisés Kaufman are taken from Mark Bly’s book, New Dramaturgies: Strategies and Exercises for 21st Century Playwriting, Routledge, Abingdon, 2019.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Mary Davies.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.