Welcome back, John Boyega. Less than a decade ago, he was an unknown budding British stage actor, then he took off as a global film star thanks to his role as Finn in Star Wars: The Force Awakens, and after his debut in Attack the Block, the comedy sci-fi flick. Following these extraterrestrial excursions, Boyega is now back on earth, his light sabre put away, and playing the lead at the Old Vic in Georg Büchner’s 1837 classic, Woyzeck, translated this time by Jack Thorne, the playwright who wrote London’s two-part super-hit, Harry Potter and the Cursed Child.

It’s a radical rewrite. Gone is a lot of the mystery and the poetry of the original. In their place is a contemporary, accessible version which emphasises realistic psychology (a lot of backstory detail) and social realism (a lot of childcare detail). The rewrite is justified by Büchner’s text, which is famously incomplete and fragmentary. Thorne includes some heightened passages from the original, which stick out a bit like bruised thumbs from the pervading ordinariness of the surrounding text. The result is an uneasy coexistence of elements, which might (at a pinch) be seen as mirroring the central conceit of the play, which is set around a British military base in Berlin in May 1981.

Stuck in the pervading Cold War stalemate, Frank Woyzeck is a British soldier who lives with his common-law wife, Marie, above a halal abattoir in this divided city. Having disgraced himself while on active service in Northern Ireland, he has few friends and is not helped by the fact that the love of his life is an Irish Catholic. Talk about sleeping with the enemy. With a newborn baby, the couple is poor (they can’t afford a buggy), but initially happy. Frank has one mate, Andrews, whose sexual exploits provide some much-needed humour in what can be a depressing tale.

Despite the boredom of their routine (Frank and Andrews do a lot of guard duty), Woyzeck is not completely unpopular. His commanding officer, Captain Thompson, favours him, and, to raise money, he manages to persuade a German doctor, Martens, to let him participate in a drugs trial. But a combination of factors — the psychoactive drugs, his abusive foster mother, worries about his child, his need to be loved by Marie, Andrews’s raging affair with Maggie, the Captain’s wife — gradually pushes Frank to the edge of a breakdown.

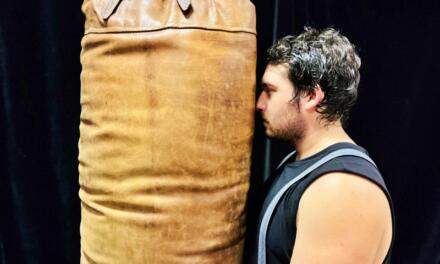

If the text of the play is sometimes over-explicit, Joe Murphy’s production is coherent and extremely powerful. Tom Scutt’s brooding design uses huge padded-cell screens that trap the characters into darkened constrained spaces, while nightmarish imagery, from bright red exposed entrails to a redcoat evocation of the British Empire, illustrate Woyzeck’s descent into a mental hell. Boyega displays a great deal of muscular versatility in his journey from naïve low self-esteem, aware of his character’s shortcomings, through a dangerous anger to his final collapse. His physique is impressive; his expressivity covers the bases. He dominates the stage, using some pumped-up gestures (frequently slapping his own head), and the play is very much seen through his eyes. At the end, he achieves an Othello-like dignity in suffering.

At times all of the acting feels like it’s on steroids, and a sense of hyperactivity energises the whole cast. As Marie, Sarah Greene gets a lot out of a much-expanded role and convincingly shows a woman driven into a corner, while the crowd-pleasing sex scenes between Ben Batt and Nancy Carroll (the vigorous Andrews and the snobby Maggie) are proud, almost excessively vulgar. Steffan Rhodri and Darrell D’Silva steer the Captain and the Doctor away from cartoonish exaggeration and towards a fractured humanity. As a picture of working-class men, this Woyzeck is powerful and effective; what gets lost is some of the poetry and much of the subtlety of the original.

This review was originally posted at sierz.co.uk. Reposted with permission of the author. To read the original review, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Aleks Sierz.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.