The quiet drone of a tanpura marks the meditative beginnings of a new solo performance that opened last week at New Delhi’s Max Mueller Bhavan. Muhnochini, directed and performed by Shardul Bhardwaj, is an excursion to the nation’s Hindu heart of darkness embodied by Tatha, a village priest who claims to have discovered the mythical river Saraswati. The play is part of a performance series called Refunction, a Goethe-Institut initiative that supports works by young, independent theatremakers, the grantees for which were selected via a Delhi-specific open call for applications. Muhnochini is one of this season’s three projects.

Caught in the middle

Over the span of roughly an hour, Bhardwaj attempts to get under the skin of the unsettling ideologue Tatha, who is ensconced in a sanctum sanctorum forged around an arrangement of rocks that provides access to a palaeochannel in which ancient water still gurgles. The priest’s demeanor and diction evoke a latter-day Maithili pandit, and his spiel is an odd mix of Vedic puritanism and contemporary rationale, especially when the principles of science must be disingenuously harnessed to further the half-truths of religious dogma. Tatha is a figure caught in the confluence of the feminine energies in his midst—the river itself, his own sister coming of age in the most parochial of settings, and the eponymous demoness wreaking havoc in the village. The eternal Indian paradox of worshipping the female as divinity while fearing women in the flesh is realized in his person, as we slowly move from petty superstitions and prejudices to a more chilling denouement.

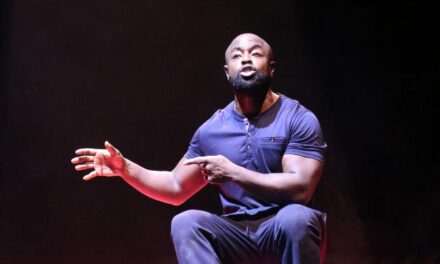

Clad in regulation maroon overalls—its sleeves filled with salt that occasionally spills on stage—Bhardwaj plays Tatha as a presence lost in his own moorings, whose composed veneer give us no indication of the depths to which he might plunge. With its oracular cadences in a minimalist setting, his performance demands unflinching attention almost without relief, mitigated only by the occasional but spurious interactive moment or when the visible technicality of grappling with a salt-filled costume pulls him out of character. Even at just arm’s length, the distance between Tatha and his observers is never entirely bridged.

The play was devised by Bhardwaj and a team of collaborators, including Siraj Sharma, Noel Sengupta, Palak Verma, and Afreen Sen Chatterjee. They appear to have struggled between the temptation to satirize Tatha’s conditioned fanaticism—through dialect comedy, for instance—and the need to probe the upper-caste radical psyche. What emerges is not so much a psychological portrait than a metaphor for the portents heralded by entrenched extremism. It is a construct that tells us more of the liberal anxieties of its makers and how they perceive the “other” as almost necessarily grotesque and terrifying. This ironically ties in with Tatha’s own fear of his sister’s burgeoning sexuality and firebrand spirit, as well as the attributing of the ghoulish happenings in the village to an obscure feminine power —the muhnochini who is never seen, only heard, who leaves young men with mauled faces and weakened dispositions in her wake.

Honor and shame

To place things in some perspective, Bhardwaj’s application to Refunction invoked the real-life event that sparked this exploration—the murder of Pakistani YouTube sensation Qandeel Baloch, whose provocative views and exhibitionist streak raised hackles with conservatives. Asphyxiated by her own brother, Baloch became a cautionary tale that held manifold lessons for society at large. In Muhnochini, the unraveling of Tatha’s soul is effected by an honor killing of similar purport. Fear unleashes the demon within, but when its agent is an oversimplified archetype, as Tatha undoubtedly is, it brings us no closer to examine the fissures in society or the fault lines along which modern tensions form. Focused on the idea of divine sanction and the pre-ordained primacy of men, Muhnochini sidesteps the tribalism and cultural norms that feeds patriarchal structures, without acknowledging that fundamentalism lies along a spectrum.

It is a narrative that places a man center stage as he wrestles with the feminine forces that take him almost to the edge of derangement. This inevitably and disconcertingly excises the female voice from the proceedings, which might be symptomatic of society at large but it does beggar the question of what such a reinforcement might achieve in reality. Muhnochini is ultimately a mirror with its own well-intentioned gaze, but its call for introspection is impeded by its own unfortunate short-sightedness.

Disclaimer: This writer was part of the jury that selected this year’s grantees for Refunction.

This article originally appeared in The Hindu on November 13, 2018, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Vikram Phukan.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.