Eve Leigh is an experimental playwright who has tackled difficult issues for more than a decade. Yet most members of the public will know her, and her actor husband Tom Penn, as the neighbors who recorded an altercation between Boris Johnson and Carrie Symonds in June this year. At least, that’s what it says on the internet. But don’t let this distract you. Her new play, Midnight Movie, marks her proper debut at the Royal Court and takes as its subject the hypnotic attractions of the net. In particular, it explores the way that people with a disability can use the digital world for good as well as for ill. Since both Leigh and her director, Rachel Bagshaw, have disabilities, they know what they are talking about.

Leigh, whose previous work has included accounts of the trauma of neglect, loss and the use of mental institutions to punish dissidents, explores the experience of surfing the internet in the middle of the night when everyone else has gone to sleep. Being Extremely Online. For her, being sleepless is a battle: due to a medical condition, she’s in constant pain and the internet is a welcome distraction from discomfort. So she flips open her laptop. Hits a search engine. What does she find there? Oh, the usual: images, ideas, and stories. She likes weird. So she jumps from one weird thing to another, then presses a previous tab and repeats a previous image or sound or word meal.

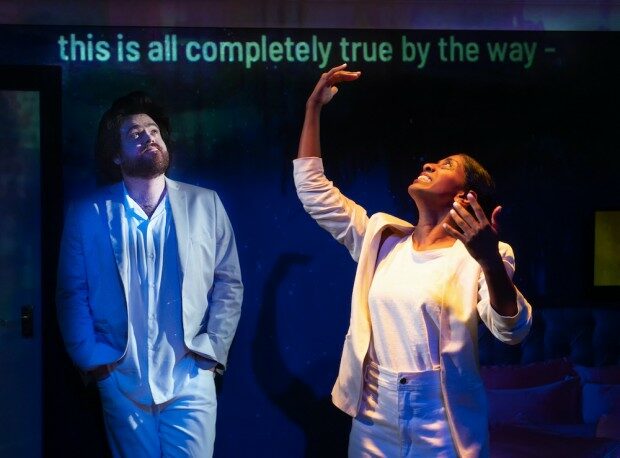

For about 75 minutes it feels as if we are in the middle of Leigh’s intimate experience of the digital world. As Joe Orton once joked, “It feels real, so it must be real.” But is it, er, really? Two performers play avatar versions of her, one a large bearded man and the other a deaf Asian woman, inviting us into the playwright’s head, but with a twist. Her words are communicated by alternative versions of herself, and maybe there’s a freedom in that. In a collage of vivid impressions of all kinds, she shows an avalanche of strange stories: a woman fights an invisible monster while trapped in an LA lift, a man takes a bath in a hotel room, silicone ants eat digital memories, a goddess from Delhi loses her power to hold water in her bare hands. It is mainly, as Leigh admits, “some wank on the internet”. Oh well.

The good news is that Leigh can really write. There is something so touching, so raw, about the pain that soaks through the show like night sweats drenching your T-shirt. Whatever the ethics of using autobiographical material for public display, putting yourself so disarmingly on the line, it’s hard to deny, or decry, the power of the core emotions on show here. Leigh comes across as an anguished spirit, but one capable of mocking herself and her obsessions; her physical pain is also mental pain; her loneliness is occasionally palpable. On a more cerebral level, there are two big ideas in the show.

One is the concept of the midnight movie and the other is the idea of the digital human, the digital body. The midnight movie is any piece of film that is so weird, so inexplicable, that you could never see it at the cinema or on television. It might be voyeuristic, sadistic, Big Brotherish or a murder mystery. Weird scenes inside the cold mine; terrible things you really don’t want to know about. Intimate moments caught online. A drive-in from hell. The digital body is our internet being: if you are unhappy with your real body, or if it has let you down, why not create an online persona: you can be anybody you like. This feels liberating, even when you are trapped into compulsively trawling through websites. Of such paradoxes is this play composed.

Of course, it is difficult to represent the cool life of the screen in three-dimensional sweaty reality. Leigh tries to break down the distinction between the two by saying that she has a visual disorder which means that she actually sees in 2-D. On stage, the play is set in an attic bedroom, designed by Cécile Trémolières, with a pink bed, and the two avatars are dressed in white suits. While Penn speaks the lines, Nadia Nadarajah performs by signing; at various moments, they play the drums, dance, and sing, and the play’s words are projected on the back of the stage. With its signing, audio description and captioning, this is an inclusive performance. At the same time, there is a service called The Digital Body, for all those who can’t make it to the theatre. You sign up to get random emails which have the same sensibility as the show. Go for it!

Fittingly, the press night took place on Unesco’s International Day of Persons with Disabilities, and Bagshaw’s production has moments of sly humor and, at its best, reminds us that sometimes we can never really know what even our nearest and dearest are thinking, are feeling. Penn and Nadarajah have a good onstage chemistry, but despite the intelligence and sensitivity of the writing — which is occasionally subjectively intense — the show is oddly unengaging. I wanted to love this Midnight Movie, but — like almost any screen experience — I couldn’t quite connect with it. Despite some disturbing passages, it feels like less than the sum of its parts.

This article was originally posted at Alex Sierz and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Aleks Sierz.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.