The second “Mandelshtam-Fest” took place at Voronezh Chamber Theatre on December 8–10, 2017.

“Mandelshtam-Fest” is a biennial of poetic and theatre art that was initiated by Mikhail Bychkov, the artistic director of Voronezh Chamber Theatre. Its program includes lectures, poetry evenings, performances, concerts, theatre showcases, and an exhibition. The festival is in honor of Osip Mandelshtam (January 3, 1891–December 27, 1938), one of the most famous Russian poets of the early twentieth century, who is also famous for his prose, critical articles, and translations. He was arrested in 1934 for critical verses on Stalin and was sent to a three-year exile in Cherdyn and later in Voronezh, in south-east Russia. In May 1938, after a short time in Moscow, he was arrested again and died in the prison camp “Second River” in Vladivostok. The Voronezh exile period was very important for his creative heritage.

Bychkov opened the festival with a speech about the actual situation in Russian art and culture, the gap in the society that we see in connection with the case of the “Seventh Studio”, the generation of people who do not understand the artist’s work, and the opposition of the artist and the state. He expressed support to Kirill Serebrennikov and Alexey Malobrodskiy and joined a poetic performance reading the verses of executed poets Osip Mandelshtam, Alexander Vvedenskiy, and many others.

Portraits of those poets could be found by visitors at “The Library of Murdered Poets,” an exhibition from St. Petersburg artist Grigory Katznelson. The exhibition, the way it was made and arranged, left one of the strongest impressions on me from the first day of the festival.

One of the specific features of “Mandelshtam-Fest” is that it commissioned two bright, outstanding young Russian directors to do experimental works devoted to the name, art, and times of Osip Mandelshtam.

The “Twilight of Freedom” work-in-progress by Anton Malikov was presented on December 8, during the first day of the festival. It was a figurative collage with musical and video inclusions that embraced emotions and thoughts based on the pre-revolutionary period of Mandelshtam’s life, which came to the end in 1918, and concluded with the creation of the poem “Sumerki svobody” (The Twilight of Freedom). This poem tells about the shift in the times and peoples’ lives, about hope for the better and inevitable loss before building something new; but at the same time it brings feeling of uncertain future, which can be terrifying as well.

Malikov mixed quotes from Mandelshtam’s letters and poetry with the quotes from “Nausea” (1938) by J.-P. Sartre. He put a Father, a Mother, and a Son into the semi-routine and semi-artificial world of a room with ordinary objects (sofa, table, chairs) and a linear labyrinth on the floor. All of that was made even more complicated by the sound design that included “Lonely Boy” by Benny Hill, “Stabat Mater” and “Der Doppelganger” by Franz Schubert, and “The Poem of Ecstasy” by Alexander Scriabin.

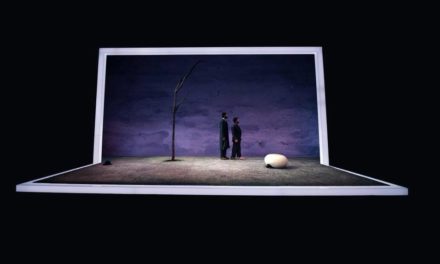

Dmitry Volkostrelov presented his “Stone by Osip” work-in-progress on December 9. He decided to create a structure out of the deconstructed text of Kamen (The Stone, a 1913 poetry collection by O. Mandelshtam); all poems were cut by line and mixed. Anton Hitrov mentions in his review that,

The work was divided into five parts, which differed one from another only by mise-en-scenes and were named “Denial,” “Anger,” “Bargaining,” “Depression,” and “Acceptance” (following the Five Stages of Grief by Elisabeth Kubler-Ross). Performers sat at the table in pairs and pronounced the deconstructed text, imitating a dialog. After each part there was projected on the wall instruction for those who would like to leave the hall. Four interludes included quotes from Ways of Looking: How to Experience Contemporary Art by Ossian Ward.

Volkostrelov’s work ended with a pure, beautiful, symbolic point – on the empty stage there was a table with glass ashtray and a lighted cigarette. The finale lasted as long as the cigarette smoldered. It reminded me the Pam Skelton video installation Burning Poems (2005).

I will not describe the whole festival program. However, I should note the composition of the festival days, in which some patterns began to appear while one was living through them.

The educational component, represented by two extraordinary lectures, was very important both for the festival design and for the audiences. One lecture by the poet, writer, researcher, and columnist Dmitriy Bykov was devoted to Sergey Rudakov – a close friend of Mandelshtam’s during his Voronezh exile, who left in his archive unique records of certain poems, comments on them, and biographical evidence.

The second lecture, by Dr. Elena Alexeeva, has opened once-inaccessible resources of the library of Princeton University, which stores the archives of Osim Mandelshtam and his wife Nadezhda.

Dr. Elena Alexeeva speaking at Mandelshtam-Fest, December 2017, Voronezh, Russia. Photo credit: www.facebook.com/chambervrn.

There were also live readings by Moscow poets Dmitriy Bykov and Evgeniya Lavut, who read their selected poems. Local Voronezh poets Galina Umyvakina, Valentin Nervin, and Elena Dudukina performed during the final festival day, reading poems covering the “Poet and State” and the “Poet and City” themes.

Galina Umyvakina as the curator selected three Voronezh poets of the Soviet period – Anatoly Zhigulin, Alexei Prasolov, and nearly forgotten Viktor Polyakov – to present their poems and remind the audience about them. The name of Anatoly Zhigulin is symbolic, as he was arrested in 1949, while a first-year student, accused of conspiracy to remove Stalin from power and of organizing the “Communist Party of Youth” and sentenced to ten years at a maximum-security camp. In 1955 he was granted amnesty and freed, and in 1956 he was fully rehabilitated. The prison camp memories made a significant part of Zhigulin’s prose and poetry.

Last but not least, I want to mention the concert of contemporary composer Alexander Manotskov, who performed with the “Courage Quartet” the “Psalms and Dances” program. This program is a brilliant combination of short songs, psalms, and dances based on verses of diverse Ukrainian poets, spiritual texts, and two poems of Osip Mandelshtam.

During his performance, Manotskov touched on the situation around the so-called “Seventh Studio” case and Kirill Serebrennikov, saying: “I think that in this country if any art event happens, every person who comes out to the stage should say something on the topic. It is even more true to me because they are my friends and partners. I hope everyone here understands that these people are absolutely innocent and that the accusations against them are meaningless. In any case, I as a person, who has a direct relationship to all Platform Project and Seventh Studio events, promise you that they are absolutely pure.”

Coming to a conclusion, I should say that bringing together such a program in the beyond-the-capitols environment in Voronezh is quite a brave step on the way of building and developing the intellectual audience in the city and around the Voronezh Chamber Theatre.

Mandelshtam-Fest is important as one of the few poetry/literature-driven art festivals in Russia. It creates the unique platform for experiencing diverse forms of interactions between poetry and other arts, society and contemporary media. It complements the cultural canvases formed by the International Platonov Festival, and I do hope that in two years we will be able to meet again during the Third Mandelshtam-Fest.

See the full program for the festival at the theatre’s website.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Maria Kroupnik.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.