Using the tools of the circus, performance art, modern dance, and puppetry, the French director and choreographer Raphaëlle Boitel has created a spectacular landscape in her marvelous production of When Angels Fall. This movement-based piece (there is no dialogue whatsoever) excites wonder and sadness, hope and despair, human beauty in a world of mechanization.

The story of the piece is ambiguous and made all the more resonant because of it. We are given very few clues as to who these people are, where they are, why they are there, and how they relate to one another. The answers to these questions are only suggested as we watch the ensemble participate as characters, dancers, technicians, and puppeteers throughout the piece’s mesmerizing seventy minutes. We get the sense of a post-apocalyptic realm. Are they humans? Are they angels? In either case, the characters are insistently lonely throughout the piece as they attempt to connect with one another, with machines, with the lights that track them throughout the piece. When Angels Fall pulses with an undeniable melancholy, but it is often lifted by moments of clown and circus, whimsy, and curiosity as well.

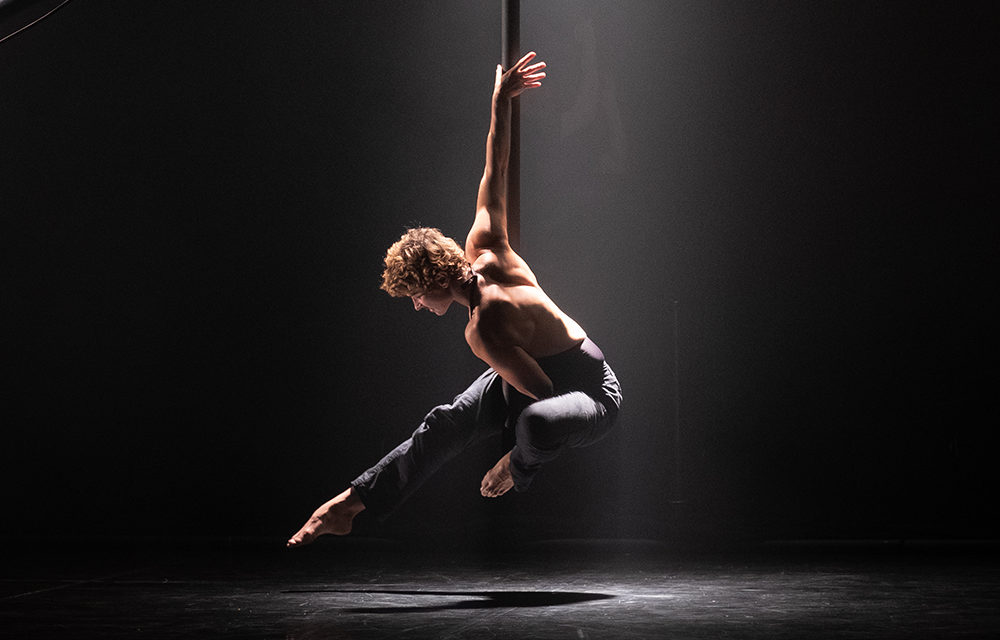

As mentioned in a recent interview with TheTheatreTimes.com, the ensemble is made up of circus performers, but When Angels Fall is not the circus. The performers are pushed “beyond their craft.” We witness human bodies complete amazing feats, climbing scaffolding and lifting themselves to the heavens. But they are also constrained by their bodies and, at times, completely grounded. They stomp and cling and writhe and gasp as limbs stretch and pull against the limits of the human frame. At one moment, three performers are trapped in over-sized trench coats that hang six inches above the stage. Their bodies dangle as their limbs jitter and shake. At another moment, a performer climbs a Chinese poll, scaling to the heights of the stage, only to fall and slide down to earth. Another performer is pushed past the proscenium frame and over the audience’s heads on a loose piece of scaffolding. The circus techniques are on display, but they employed at the service of the story and the poetic image.

There are also tremendously funny moments of clowning in When Angels Fall. With the same mildly concerned look and deadpan as Buster Keaton, a character futzes with a contraption that keeps falling apart piece by piece. Every attempt he makes to fix the contraption makes another piece of it go awry. The same character, upon encountering a gramophone, barks, and shrieks as he attempts to replicate the sounds. He ends up screaming into the gramophone, perhaps yearning for connection, hoping to hear some sort of response. At another moment, the characters find themselves in a shooshing match and, like a snake eating its own tale, each character attempts to silence the others as they, in turn, get shooshed. The lazzi heightens as the shooshes become more violent, more exasperated, and more frenetic.

Boitel’s close collaborator is set and lighting designer Tristan Baudoin, whose influence on the piece is vital. The lights become personified and characters in and of themselves, as they track the performers, leaning closer, bending towards them with an almost curious glint. Controlled and manipulated as if puppets by the ensemble, the lights trap the performers and seem to have a controlling effect on the characters. At times, the lights appear menacing as they survey and trace their movements. At other points, the lights provide a friendly presence, akin to Pixar’s lamp or its robot Wall-E. The lights also create vivid images as they cut a bare stage filled with dense, billowing smoke, catching the performers’ bodies as they dance, and climb, and move through the air. The lights shimmer on the performers’ bodies, creating a stunning chiaroscuro effect, as light and dark, human and machine complement one another.

When Angels Fall is another welcomed-entry among the many talented and compelling circus-based companies in ArtsEmerson’s repertoire, including Les 7 Doigts de le Main and Machine de Cirque. Boitel’s sensibilities have led to a marvelous piece that possesses all the poetry and tour de force acts of these other companies. It is also imbued with an existential quality, a dark and desolate landscape that is still lifted by an ever-present sense of play and wonder. The only downfall is the evanescence of the piece. I was sad when it was over, just as I was sad that Boitel and her company played in Boston for only a short amount of time.

Presented in co-production by Cie L’Oublié(e) and ArtsEmerson, Emerson Cutler Majestic Theatre, 219 Tremont Street, Feb. 20-24, www.artsemerson.org.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Matthew McMahan.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.