The opera, which is based on a short story by Colombian writer Gabriel García Márquez, finally premiered in Budapest. This winter, the Hungarian State Opera presented the opera, composed by Péter Eötvös as the first production of the new year.

Love and Other Demons, which is Péter Eötvös’s fifth opera, was commissioned by the Glyndebourne Festival Opera, was composed in cooperation with Kornél Hamvai, whose multilingual libretto (constructed with elements of Yoruba, Latin, and Spanish, in addition to English) is based on Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s short story of the same name.

Although the opera is based on Márquez’s story, and the story has been fully adapted to the stage, the events of the opera may lead the audience to ask “where is the love?” during the show. Eötvös represents the writer’s brand of magical realism, involving superstition, magic, and rituals (even human sacrifice) through its arresting visual life and stories that deal with the mixing of cultures. The opera is not a boring love story, and it focuses on many things other than love, such as taboos, racism, social hierarchy, demonic possession, loneliness, religious self-confidence, intolerance, and insanity, but also speaks of love as well. In truth, if you don’t know the original story, you may have a hard time understanding the love scenes or the role that the concept of love plays in the opera; nevertheless, it is there, hiding beneath the patina of fear and possession, of racism and religion.

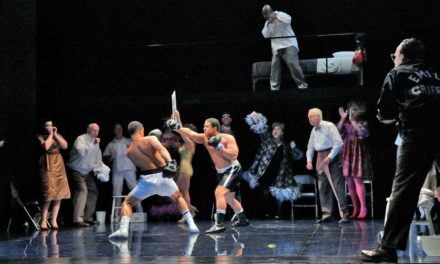

The opera is brought to life with an amazing technical support and onstage visual effects. Sometimes, operas can be too slow and drawn-out, but watching Eötvös’s show on the stage we feel as if we were in a cinema watching a movie. It is hard work to speak—or rather sing—about exorcism and to transmit that fear and thrill that demons may cause. Although the atmosphere is heavily laden with constantly lurking evil, the brilliant fireworks generated onstage by soprano Tatiana Zhuravel helps to dissolve the pressure and the stress. The video scenes in the background sometimes helped the line of the story, and sometimes also increased the thrill and pressure.

The music is confusing and carries its hearers with it. The opera begins with magical celesta and xylophone tinkling that goes on for quite a while, and that makes it feel both creepy and like random exploration by a child at the same time. From then on, Eötvös’ musical foreshadowing of what real or unreal monsters lurk is generally too ubiquitous, but his underscoring of the singers is masterful—only one or two instruments often gently accompany a vocal line instead of a thick orchestration. His instrumental effects are spare and purposeful, and fortissimo tuttis only come when necessary for the drama. His solo vocal writing is comfortably wide-ranged for every voice and his frequent tone-painting according to the words is spot-on and vocally conceived. His best compositional moments, though, are the intriguing tone-cluster women’s choruses that waft through the score like haunting mantras.

“This is my first opera about love, and also my first quasi-bel canto piece that allows the singers to show off the beauty of their voices,” said the composer. Ultimately, his opera has all the makings for an exciting theatrical experience, including a story full of operatic elements, and Eötvös himself has stated that this is his most melodic music, while critics have called it magical.

This article was originally published on Hungary Today. Reposted with permission. Read the original article.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by The Theatre Times.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.