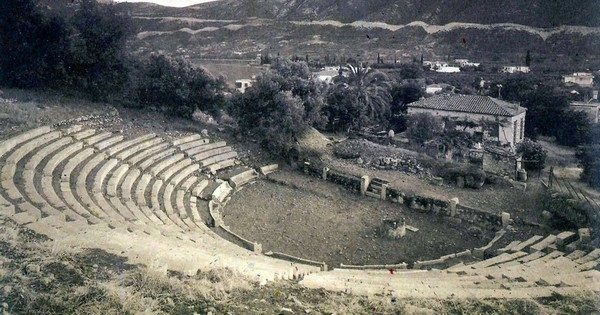

The Little Theatre of Epidaurus is placed near the port of Palea Epidaurus in the Argolis prefecture of the Peloponnese. It used to be the theatre of the ancient city-state and, apart from drama performances, it also hosted religious and political celebrations.

After several excavations and much restoration work performed over the last decades, the Epidaurus Little Theatre hosts today the annual Greek Festival, celebrated in summer with music, dance, and theatre performances. The performances are mostly held in Modern Greek with English supertitles.

In a retrospective of this year’s festival, what is intriguing in the performances held in The Little Theatre of Epidaurus is their experimental character. They are usually low-budget performances. One should not expect impressive costumes, rich theatre sets, or multimember casts. But they are actually rich in innovative ideas and invigorating perspectives about ancient drama.

This year’s program consisted of Aeschylus’, The Libation Bearers by the group VASISTAS–Argyro Chioti (July 6-7, 2018), Sophocles’ Antigone by Konstantinos Ntellas (July 20-21, 2018) and Aeschylus’ Prometheus Bound by Martha Frintzila (August 3-4, 2018).

Little Theatre of Ancient Epidaurus. Photo

The Libation Bearers by the group VASISTAS–Argyro Chioti

The Libation Bearers is the second part of Oresteia trilogy (Agamemnon is the first). The main character is Electra, mourning her murdered father and obsessing over the anticipated return of her brother, Orestes, with whom she plans to take revenge for Agamemnon. In the bleak opening, Electra mourns over her father’s grave. Her laments are added to those of the women of the Chorus, the Libation Bearers. There, she is reunited with her brother, who returns after many years abroad, together with his loyal friend, Pylades, both disguised into foreigners. Upon seeing her in mourning, Orestes realizes they will be allies and reveals himself to her in what is one of the most powerful scenes of recognition (anagnorisis) in ancient drama. With Electra’s aid, Orestes and Pylades pretend to be foreigners bringing the dead Orestes’ ashes home. After Clytemnestra welcomes Orestes, he reveals his identity to her and murders both her and her lover and accomplice, Aegisthus. The Furies arrive, relentlessly pursuing Orestes. The hero will eventually be acquitted at Areopagus at the third part of the trilogy, The Eumenides.

According to the director, Argyro Chioti, “The VASISTAS group approaches the play as a profound conflict between human instincts and social conformity, focusing on the chorus, this powerful voice that is constantly on stage, pushing things forward and inciting murder.”

The emblematic feature of this approach was the fact that the chorus and the heroes were a united group. The actors that performed the main characters became part of the chorus when they were not acting their roles. The presence of the chorus was dominant and actually persisting in vengeance and murder leaving no option to escaping. Another interesting fact of the performance was the dual nature of the main heroes. Electra, Orestes, Clytemnestra were divided into two; two actors complemented each other and the heroes’ obscure personality: a representation symbolizing the doubt, the uncertainty, the second thoughts, the discouragement, or the opposite feelings and thoughts felt and expressed by the protagonists. In this context, Clytemnestra was performed by a woman and a man. The latter impersonated the aspects of her character considered to belong to a male identity, such as audacity, cruelty, power, authority, lack of sensitivity, or motherhood. The director often challenged the idea of gender identity: the Chorus of the play is supposed to consist of women only, the Libation Bearers, but in this performance, men were members of the chorus as well. In fact, the Chorus leader that speaks to Electra at the beginning of the drama was acted by a man. Lament, suffering, social disapproval, and community control are not restricted by gender. On the contrary, feelings, expression of pain, anger, despair, wrath, violence, are aspects of our life that are often compressed inside our body, seeking an exit. Sometimes this exit becomes a corporal outburst of movements and spasms; on other occasions, it is urged or formed by social restrains that eliminate personal resistance or denial. This is the case of Orestes and Electra: their family heritage (or guilt), the social and ethical laws and control allow them no liberty of choice. These feelings of burden, of coming to a dead-end, of social pressure and expectancy exercised upon them were very eloquently expressed by the actors. It was obvious that they had worked hard and were dedicated to their roles and eventually, their mission was accomplished successfully.

Another important element of VASSISTAS’ version of the tragedy was the sound and the music. During the whole performance, the actors carried simple musical instruments, two pieces of wood, or “lyras”(a plain wood with a few strings attached to it), producing sounds and a kind of music referring to mourning. The Chorus as the dominant of the tragedy was highly supported by the sounds and the music enhancing the rhythm and the poetic nature of the drama.

Scenography, as well as costumes, was plain. A neutral, empty orchestra covered in sand. The costumes were almost identical with slight differences in colors or details. Theatrical objects were restricted to the musical instruments. The lighting organized the space by designing a (light-) corridor or focused on the speaking persons when needed.

Sophocles’ Antigone by Konstantinos Ntellas

Arguably Sophocles’ most popular tragedy, Antigone is set in Thebes, shortly after the civil war that resulted in the mutual killing of the two brothers, Eteocles and Polynices. King Creon orders Eteocles’ honorable burial. At Creon’s behest, Polynices is to remain unburied, being an enemy of Thebes. The two men’s sister, Antigone, refuses to obey the order. After arguing with her sister, Ismene, who originally refuses to help her, Antigone decides to bury Polynices on her own. Subsequently, she is arrested and sentenced to death. Creon stubbornly insists on his decision and does not yield to the appeals of his son, the lovelorn Aemon. He finally relents and changes his mind after the clairvoyant Teiresias makes him see that this decision will seal his doom. Too late, though: Antigone has already committed suicide inside her tomb. Refusing to come to terms with her death, Aemon also takes his life, followed by his mother, Eurydice, who hangs herself after hearing of her son’s death. At the end of the play, Creon is left behind, a tragic figure, one of the most harrowing characters in the entire cannon of ancient drama.

Konstantinos Ntellas’ directing focused on the human, on turning the tragic heroes into everyday people. How would a tyrant-father react to his children’s impertinence? Wouldn’t he be furious? Would he exercise corporal punishment? How would somebody react to his/her sibling heading for a self-destructive step? Ntellas’ heroes act and react not as tragic figures, distant and aloof, isolated in their own inner world, but as ordinary people who express their feelings, verbally and physically, touch or assail each other, try to communicate, suffer and collapse after the belated realization of self-destructive decisions.

Antigone by K. Ntellas, Little Thetre of Epidaurus, Athens & Epidaurus Festival 2018. Photo: Evi Fylaktou

But it was not only the heroes-actors that referred to everyday life; it was the atmosphere, the paraphernalia of the performance that linked it to its rural surroundings: the repetitive sound of the church bell calling to a burial, the voices of the animals and the presence of the people of Lygourio (the village next to Ancient Epidaurus) as part of the performance, as the people of the “polis” (=city) attending the acts and speeches of their leaders, while the village girls, after having carried an epitaph in the opening of the play, were decorating it with flowers. The epitaph is an Easter tradition of the Christian- Orthodox Church, a clear relation here to the deaths and burials at the end of the drama.

Heroes turned into Chorus’ members in this performance as well, singing the lyric parts accompanied by a small orchestra into the rhythms of Balkan folklore music. The Chorus parts were also integrated into and mixed with traditional Greek music culture (for example, with “moirologia,” traditional mourning songs).

Antigone was presented in clear relation to today, with the place–Epidaurus–and its people, their tradition (religion, customs, music) and their environment (scenery, sounds). The acting aimed at expressing and communicating thoughts, feelings, instincts, psychological swifts, and intimate relations. Very interesting was the idea of Teiresias impersonation: a compilation of two actors, a man, and a woman, in permanent, slow movement, alternating their voices as the blind clairvoyant. The implication referred either to his attached-boy-guide and/or to his double nature: the only human who lived as a man and as a woman. The constant movement of the two actors and the change in voices and tones mastered skilfully Teiresias’ turnarounds of temperament. Generally, the cast was very loyal to the principles of immediate and expressive acting, with the exception of Antigone whose speech in a number of cases seemed to recite rimes.

Scenography was simple as well. Only some grass and small plants here and there, among the small stones, repeating the natural environment. Costumes followed the same idea: one color, simple midi dresses for the women, shirts, and trousers for the men that turned them into everyday-villagers.

Aeschylus’ Prometheus Bound by Martha Frintzila

The last performance, Prometheus Bound, was the only one differentiating in elaborate scenography, costumes, and in the autonomous Chorus as well.

Prometheus is punished by Zeus for giving fire to humanity. Hephaestus chains Prometheus on steep mountain rocks, with Cratus and Bia keeping watch. Oceanus’ daughters, the Oceanids, lament the hero’s torment. Prometheus and Oceanus discuss Zeus’ cruelty. Enter another being who has suffered the wrath of the gods: Io, Zeus’ mistress. He once transformed her into a heifer to save her from Hera’s jealousy. Hera then dispatched a gadfly to mercilessly follow Io around to the end of the world. Prometheus recounts her past travails and predicts her fate, interlinked with his own, since a distant descendant of Io is destined to set Prometheus free several years in the future. Prometheus also foresees the fall of Zeus. However, he refuses to disclose the exact circumstances of Zeus’ fall to Hermes, the messenger god. The tragedy ends with a raging Zeus unleashing his thunders against Prometheus, the still-resisting prisoner who retains his free will.

Promitheus Bound by Martha Frintzila, Little Theatre of Epidaurus, Athens & Epidaurus Festival 2018. Photo: Evi Fylaktou.

Prometheus is a Titan, immortal, equal to Zeus and older than the twelve gods of Olympus. But he is exiled, tortured, and suffering from the new divine hegemony. In Frintzila’s performance, Prometheus is set in a very high seat with a huge, gold-plated square in the back that reflected light. Although he is supposed to be bound, he actually retains freedom of moves: he stands, sits, turns around. He never leaves his “cursed throne,” though. From his position he watches everything and everyone moving on earth, people or minor gods, like Cratus, Bia, Oceanus, Io, and discusses with them. Next to him, but at a lower level, stands the Chorus of Oceanids. They are compensating to him.

The Chorus set out to be the other protagonist of the drama. The ethereal voices of the Chorus singers that accompanied Prometheus in the greatest part of the play, and their subtle gestures, as well as the movement of their long white dresses, were persuasive of being the light, unearthly creatures flying in the air around him. The Chorus consisted of the music group “Fonέs” coached by Marina Satti and was absolutely impressive as a well-tuned ensemble. The authentic live music of Vassilis Mantzoukis enforced the melodious impact.

Two big metal and iron constructions covered the orchestra. In the middle, there was a table made of long iron bars that were moving producing a wavelike effect, reminiscent of the sea lying in front of Caucasus, of the clouds floating in the sky or/and of the time flying (?)… On the left, there was another metallic construction like a table with metallic logs underneath that were moving, too. It served as the podium and carriage of Oceanus. On the right, a lying high seat was set upright, on proper time, for Hermes to stand and talk to Prometheus. Scenography and scenic objects were austere and harsh reinforcing the ambiance of cruelty, severity, and dissertation that surrounds the tragic hero.

The costumes of the gods (Hephaestus, Oceanus, and Hermes) were voluptuous: big round hats with gold plates hanging on them, and very long dresses with embellished textiles. Io was quite sexy dressed in a cow skin body walking on too high platforms that made walking hard, often forcing the actress to bow or crawl. On the contrary, Prometheus was dressed in simple black clothes and barefoot, while the Chorus in plain long white dresses carrying masks on the top of their heads.

The director stated that “In this performance we will focus on the power of language and spoken words, reciting the text in a rhythmical and melodious manner.”

The truth is that the outcome verified the above statement. The words of the tragic play were transmitted fluently and clearly by all the actors while the music and the choreographed movement refined the aesthetic effect of the drama.

Overview

Looking back, all three performances focused on the role of the Chorus; through different means of musical and theatrical expression, they tried to highlight its prominent presence in the Greek tragedy. It displays the unity, the unanimity and the power of the people of the “polis,” mourning, pressing the heroes for revenge and action and, at the same time, it functions as a vocal and singing escort emphasizing the poetic nature of the tragic speech. Furthermore, they all refrained from the old-fashioned, dramatic but excessive and distant manners of tragic acting, even though they didn’t lack passion or tension. They stayed close to the text and its poetic character. The directors focused on the speech in order to deliver clearly its meanings and ideas, on the sounds, on the music, and on scenic simplicity.

Apart from these elements in common, the audience enjoyed three different in aesthetic outcome, but very interesting approaches of how an Ancient Greek Tragedy can be interpreted today.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Katerina Leoudi.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.