Paula Vogel’s How I Learned to Drive is, famously, the play that blew the lid off the subject of pedophilia in the theater. At its premiere in 1997 it was startlingly fresh and shocking—not because most people had never heard of such abuse but because the play painted such a uniquely detailed picture of exactly how it occurred, and was abetted and perpetuated, within an ostensibly ordinary and loving family. My most vivid memory of Mark Brokaw’s searing original production is of the knot in my stomach walking out. The play was so plausible in every nuance it made me grasp for the first time just how common such scenarios are in real life.

Now Brokaw, 25 years later, has restaged the play on Broadway with the same extraordinary lead actors—Mary-Louise Parker and David Morse—and watching it makes me realize how much water has passed under this particular bridge in the meantime. An avalanche of other plays about pedophilia followed How I Learned to Drive, from Frozen and Doubt to Blackbird, The Nether, Downstate and many, many others, examining the subject from myriad different viewpoints. This surge of stories left us wiser and also a little jaded, especially after the rash of #MeToo-driven scandals involving famous predatory men and the hundreds of testimonies, books and documentaries that followed. The upshot is that Vogel’s play can’t shock in the same way anymore. It still has power, but of a different sort.

Drive is a fractured memory-play that jumps back and forth in time. In the opening scene, set in 1969, 17-year-old Li’l Bit (Parker) sits in a parked car with an older man (Morse) who talks her into taking off her top. He turns out to be her uncle Peck, a reveal that felt like a bombshell in 1997. Today, most people know who he is going in (the play is that famous), so we watch for the subtleties of how all his inappropriate encounters with his niece play out. Sessions of driving instruction-cum-sexual grooming alternate with family scenes showing the willful obliviousness, even passive complicity, of Li’l Bit’s aunt and grandmother. The predation, we learn, began as early as age 11, and Li’l Bit’s memories of her flirtatiousness make clear that she believes she shares blame.

Perhaps the most original and disturbing aspect of Drive was always the sympathy with which Vogel wrote Peck. Refusing to demonize him, she gave him qualities anyone might admire—courtesy, thoughtfulness, kindness, and most important, sympathy for Li’l Bit’s intellectual ambitions (“You’ve got a ‘fire’ in the head”) that no one else in her crude, lowbrow family offered. In 1997, when Morse was 44 and Parker was 33, part of the play’s creepiness was that their relationship was truly charming onstage despite being despicable. The actors, after all, were age-appropriate for romance and had steamy chemistry, and the “reality” of childhood and adolescence in the play was evoked solely by Parker’s virtuosic acting—an astonishing repertoire of slouches, pouts, hip sways and foot shuffles that felt themselves like extraordinarily acts of memory.

Looking back, it seems to me that that double dimension of the acting actually put the audience in a comparable dissociative state to Li’l Bit, who says that she retreated “above the neck” to process her story’s horror:

That day [of her most difficult memory, from age 11] was the last day I lived in my body. I retreated above the neck, and I’ve lived inside the “fire” in my head ever since.

That, I think, is where the knot in my stomach came from—an uncomfortably complicated visceral reaction to the horrific truth in front of me that my head strongly wanted to deny. It was a devastatingly sly Brechtian distancing effect that sharpened everyone’s feelings of complicity with a crime most of us (I presume) would not have owned.

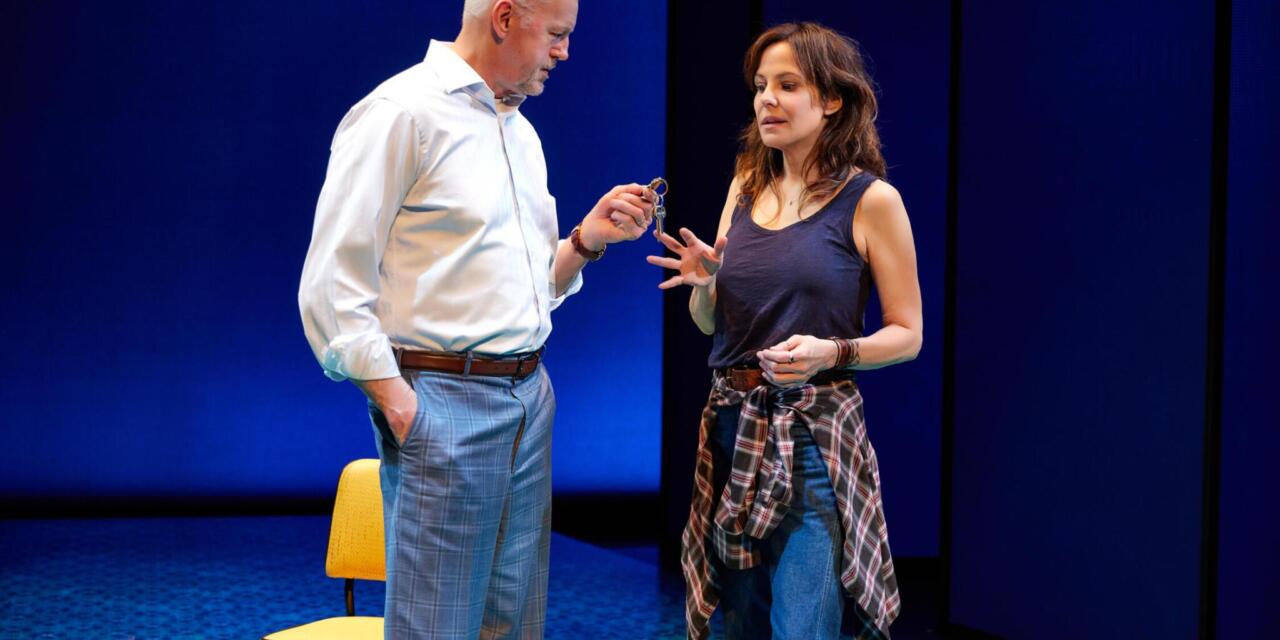

That is not the way the play feels today. At age 57, Parker’s easy access to all those physical evocations of girlhood is, if anything, more amazing than before. And yet there is no heat between her and Morse now. He, at 68, is grizzled and brittle, more like a grandpa than an uncle (made more evident by casting the very young-looking Chris Myers as the family’s actual grandpa). All Morse and Parker’s interactions seem sleazy from the outset even though both actors are reproducing their gestures and mannerisms from years ago with chilling accuracy. The play’s Brechtian distancing effects, in other words—which also include announced scene titles and a 3-member “Greek Chorus” (Myers, Johanna Day, and Alyssa May Gold) performing many other roles against type—are no longer muted or couched in an erotically charged, soft-focus memory blanket. They now assert themselves as the play’s main point, making it feel more like documentary or advocacy than poetic revelation.

PC: Jeremy Daniel

Let me be clear that the production is worth seeing, if only for Parker’s inspired performance. My wife pointed out that, given the play’s cooler, more factually oriented profile now, Manhattan Theatre Club could do a world of good by making the show available free or steeply discounted to teenagers. They are the ones, after all, who still truly need to hear this appallingly true story in all its detail, despite whatever they think they know about sleaze and predation.

By Paula Vogel

Directed by Mark Brokaw

Manhattan Theatre Club at The Samuel J. Friedman Theatre

This article was originally published by Jonathan Kalb on Apr 23, 2022, and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Jonathan Kalb.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.