La Cubana have been making theatre for over 45 years – stagings that have reimagined popular genres while contemplating the dynamics of putting on a show from the perspectives of those working behind the scenes. Whether focusing on the backstage dramas of a large-scale staging of Aida in Una nit d’òpera (A Night of Opera, 2001), the characters bursting in and out of the cinema screen in Cegada de amor (Blinded by Love, 1994) or the happenings popping up in and around the streets of the Raval in Cubananas a la carta (Cubanadas on the Menu, 1988), La Cubana have offered highly accomplished and hugely entertaining performances that have often toured Spain for numerous years.

2025 sees La Cubana’s first new production since Adiós Arturo (Farewell Arturo) in 2019. L’amor venia amb taxi (Love Arrived By Taxi) has the company return to the Romea, the site of their hilarious reimagining of Shakespeare’s The Tempest (1986). La Tempestad had an (imaginary) storm raging outside the theatre, the performance halted in mid flow, and the audiences encouraged to take survival courses to help them deal with the likely flood. Their return to this legendary Catalan venue is with a very different kind of show — a homage to the amateur theatre tradition that has been so popular and so pervasive in Catalonia. Arguably some of Catalonia’s most important actors, including Margarita Xirgu, Núria Espert and Rosa Maria Sardà, have come from the amateur dramatics’ tradition and this is a show that recognises that this is a lineage with a professional quality that isn’t always recognised.

L’amor venia amb taxi sees an amateur dramatics company in Barcelona preparing a staging of Rafael Anglada’s play of the same name. It’s 1959, the year Anglada’s comedy of errors was first presented at the Romea, and the piece makes a series of references to the city, gearing up for the 1960s and the new apertura (opening) that came with new investment into Spain, a new tourist market and the sprawling urban expansion of the city under mayor Josep Maria Porcioles (1957-73) to accommodate the growing population arriving in search of work from other regions of Spain.

The piece is a homage to that production of Anglada’s play (as well as the amateur stagings that followed) and to the many businesses that supported and sustained the theatre industry in Catalonia. The narrative revolves around an amateur dramatics company in Barcelona that meet weekly on a Tuesday evening after work, at the church hall of Our Lady of the Light, from January to October to rehearse the play over many months. As with all La Cubana’s prior pieces, it maps the dynamics of the cast – the coy Maria Rosa is cast as the romantic lead, only her father, a high-ranking Lieutenant Colonel in the army, is not best pleased that she or her mother, Montserrat, are involved in theatre. Things get especially tense when she gets pregnant out of wedlock — the father to be is Eduardo, her love-interest in the show. The company are a motley group of aficionados — from the enthusiastic fishmonger Enric who doesn’t aways have time to clean up and change before rehearsals to the elderly and very religious Salvadora whose black veil announces her severity and her impeccable credentials as a voice of moral virtue.

The troupe’s veteran director, Antoni, takes rehearsals very seriously; newcomer Joan can’t explain why he does theatre “I come here because I like it” he announces shyly. The larger-than-life fishmonger Enric gives Joan lessons on projection and diction using his daily experience of selling fish. Technician Kiko is on hand to offer pragmatic help. Maria Rosa is hoping to follow in her mother’s footsteps and has secured a leading role. Rehearsals, however, are interrupted by Maria Rosa’s father, in full military uniform, who sees theatre as a hotbed of sedition and political activism. He makes noisy entrances through the aisle, accusing the company of promoting Lorca — the dramatist’s work still not staged at the time — and spreading communist propaganda, wanting them instead to do an Antonio Buero Vallejo play or something by the Álvarez Quintero brothers. The booming voice recalls that of the angry spectator Paco who interrupted Cegada de amor each time the cast spoke Catalan.

Indeed, there are many references to past shows by La Cubana. The rehearsal antics recall their TV series Teresiñas as well as their homage to travelling vaudeville companies, Cómeme el coco, negro (Nuts Coconuts, 1989). Rehearsals never run smoothly for the troupe, whether it’s Loreto’s bereavement, the frequent disruptions of the loud Lieutenant Colonel in search of his errant wife and daughter, or a double booking with a folk-dance group. Enterprise, generosity and pragmatic good sense see the locals through the trials and tribulations of putting on a show.

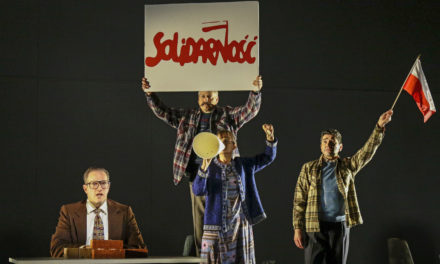

A musical tribute to the “tresillo” (three-piece suite). Photo: David Ruano, courtesy of La Cubana

There is the tale of a drunken company member falling into the prompter’s shell and the struggles to get the tresillo (three-piece living room suite) into the theatre: this episode is the focus of a very amusing musical number where the tresillo is identified as the only thing to escape the Caudillo’s (Franco’s) grasp.

There are red curtains to be sewed in the suffocating July heat, and replacements for missing performers to be found.

As in La Cubana’s previous work, audience members are roped in to help — auditioned for the Maria Rosa role, passed generous portions of Easter cake when some of the cast disappear after another of the Lieutenant Colonel’s outbursts, and thrown bags of peanuts during a refreshment break.

The cast making their way into the auditorium to share Easter cake with the audience. Photo: David Ruano, courtesy of La Cubana

Each rehearsal scene — the production features a monthly glimpse of the company at work — is followed by a vaudeville musical number from a production that could be seen in Barcelona in 1959. The audience are treated to the picturesque nocturnal landscape of “Bella Dorita” and the foxtrot of “La sombrilla” (The Parasol). “La reina ha relliscat” (The Queen has Slipped) is particularly funny, with actors dancing across the stage with cardboard cut-out costumes that they must manoeuvre as they try to move as a chorus. There are loving homages to the numbers presented at the legendary music hall venue El Molino and to popular performer Joan Capri. Painted sets by Germans Salvador (the Salvador brothers) and Castells Planas provide the backdrop for the numbers — a glorious homage to the Salvador brothers workshop in the nearby Carretes Street.

The play ends as the show is about to go on, with Montserrat and her daughter not leaving for Seville to join the newly promoted Colonel but rather staying to ensure the production opens with Montserrat taking on the role of Emilia that the heavily pregnant Maria Rosa can no longer play. Casting is not age-dependent, Loreto states, extolling a particular vision of repertory theatre that involves everyone mucking in. It is this vision of togetherness that the production extols. Reference is made to Néstor Luján’s negative criticism of Catalan theatre in the magazine Destino in 1959. The company galvanises around their own production just as the profession galvanised to prove Luján wrong; L’Escola d’Art Dramàtic Adrià Gual was established by Ricard Salvat and Maria Aurèlia Capmany, in 1960 as a training initiative to further professionalise Catalan theatre.

The production is generous in its nods to a whole ecosystem that sustained Catalan-language theatre during the difficult years of the Franco regime. There are references to the costume workshop of the Peris brothers that closed in 2004, the wigmakers Damaret on the Ramblas that produced headpieces for many theatre productions and the legendary publishing house Milla on Sant Pau Street. The latter, founded in 1901, only closed its doors in 2015 and was responsible for publishing a huge range of Catalan-language plays.

The script, written by director Jordi Milán with Toni Sans and Rubén Montañá, draws on tropes familiar to fans of La Cubana: audience participation; the focus on community; the ticking clock of rehearsals or the show that is underway with disruptions threatening successful completion; the dizzying array of characters played by the company of 20. There are company veterans like Toni Sans and Maria Garrido. Anna Barrachina (the precocious “child” actor Estrellita in Cegada de amor) is glorious as the pious Salvadora. But it would be churlish to single out performers when the whole ensemble is this terrific: Nuria Benet, Xavi Tena, Àlex Gonzàlez, Montse Amat, Bernat Cot, Oriol Burés, Laia Piró, Víctor G. Casademunt, Rubèn Montañà, and Albert Mora. All offer a terrific humanity to their roles: characters whose wigs begin to slip off, whose costumes that don’t fit as well as they might do; who might not have memorised all their moves or make a noticeably late entry in a musical number. Whatever goes wrong, the company fumble through with humour, hard work and good will; and it is glorious to watch.

The cast spill over into the auditorium and the actor-musicians are integrated into the action. Photo David Ruano, courtesy of La Cubana

Joan Vives and Xavier Mestres’s musical numbers are a delight — witty, smart and catchy with the final number “For the love of art” reinforcing the company’s commitment to an artisan ethos of making and mending. The actor-musicians are also part of the action — at times on the first-floor balcony, at times taking the stage: Xavier Mestres on the piano, Laia Ferrer Vila on the violin, Helena Capdevila on the accordion, Xavi Sánchez on double bass, Ferran Casanova on sax and clarinet and Jan Espinach Rota on percussion and drums. All are part of the action. For 145 minutes La Cubana transport the audience to their version of what the theatrical milieu of 1959 might have felt like. As the final credits roll and photographs of productions from 1959 recreated in the show are projected on the back screen, past and present fuse: a reminder that any piece of theatre will always reflect history through the lens of the present. Here La Cubana celebrate 45 years of making work by reminding each other and their audiences why it matters to work together with empathy and care while taking time to remember (and celebrate) those who made work during the difficult years of the Franco dictatorship.

L’amor venia amb taxi (Love Came By Taxi) plays at the Teatre Romea Barcelona from 17 September 2025 to 15 February 2026.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Maria Delgado.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.