Maša Ogrizek (1973), a university graduate in Sociology of Culture and a philosopher, has been self-employed in culture as a critic and writer since 2008. She has published book reviews, interviews, and articles in the field of sociology of everyday life in Delo’s Literary Lists, Bukla, Dnevnik’s Lenses, Views and Faces; He also writes book reviews for Radio Slovenia. He lives and works in Ljubljana. Bibliography (2018-2013): Koko Dajsa In The City, Mouse Publishing House; Lady with a Hat, Youth Book (Ranked among the 5 nominees for the 2017 Levstik Award); Great Story, Mouse Publishing House; Ko-Ko-Krishna, publishing with Trieste Press (2014); The Elephant on a Tree, Publishing House of the Trieste Press (listed among five nominees for the Kristina Brenkova Award for the Original Slovenian Picture Book); Sinjerdeča, publishing with Trieste press.

Ivanka Apostolova Baskar: Maša, who is the lady with a hat? Is she is your alter ego, or pseudonym, or it is just a playful creation?

Maša Ogrizek: This character is based on a real person – the old aunt of my two children. They share the same name and occupation: Ljudmila, and both of them were dressmakers, which they both hated, so they are happy to be retired. I also model the appearance of literary Ljudmila on the real one. But you are correct, in a way she is also my alter ego, because I give her a lot of characteristics that I value the most: curiosity, good-heartedness, comradeship, humor, optimism. In a way she also represents rebellion against social norms of any kind, including gender roles, so that is one of the reasons why she wears a hat. In one period of my life, I liked to wear one myself.

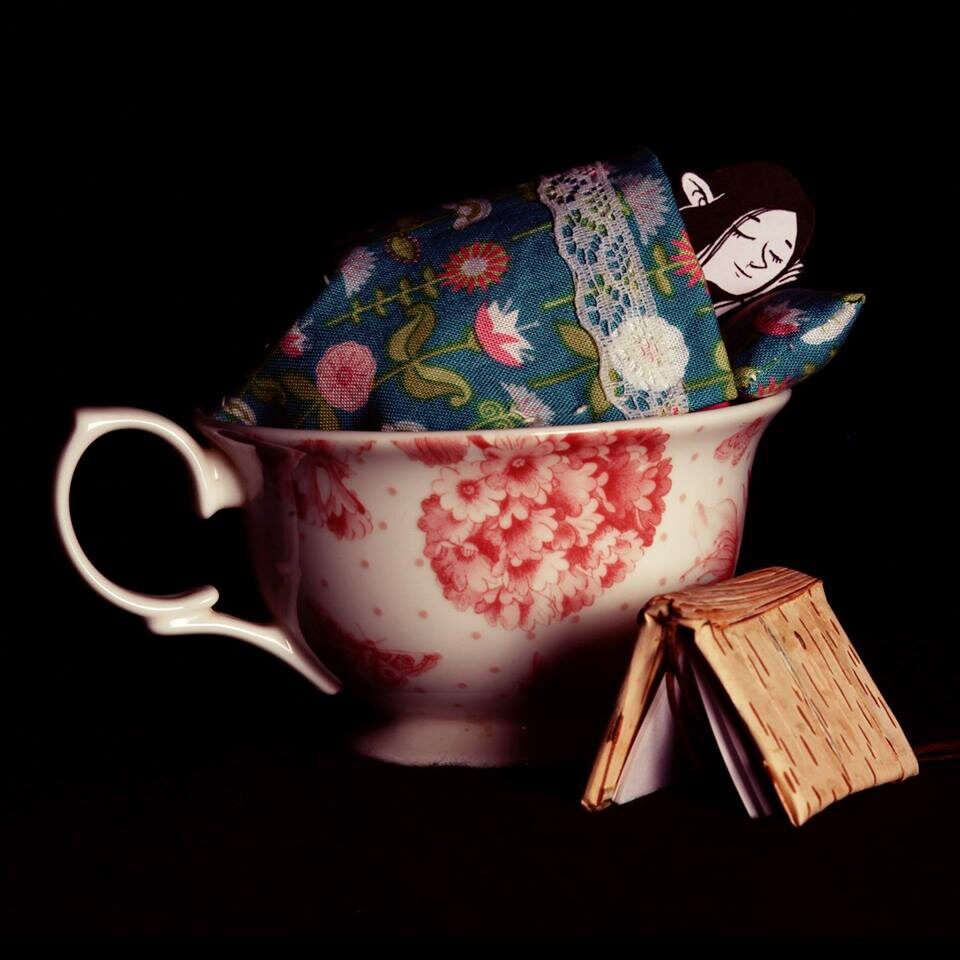

“Lady with a Hat”. Photo courtesy of Masa Ogrizek.

IAB: How and where do you detect potential for a good story? How do you create and build your characters – what is the secret of your art and craft?

MO: I always start with the main characters, they just visit me. Some writers claim that they hear their characters speak to them. I have a strong visual imagination, so I see them in my head. I spend some time with them, so I get to know them: what they like to do, what their passions are, what they hate or are afraid of, how they interact with other people, etc. Then I slowly build the story around them; ideas for stories emerge coincidentally, sometimes from my subconscious, sometimes from bits of reality. When I began writing the creative flow carried me and I just surrendered. Now, I have a bit more “control” over the writing process, but I still reject starting from a “big idea” of what the book will be about. In my opinion, this must be told between the lines. It is like an elusive mist that wraps around the narrative flow. I really hate a didactic tone of voice and I think readers, especially children, don’t like it either.

IAB: What are your criteria and creative needs for choosing the right illustrator – are they a visual collaborator and co-creator in your stories and books?

MO: You put it nicely: co-creator. I like to collaborate with illustrators very closely. Usually, I include them in the process at the very beginning – we discuss plot and characters together. Sometimes the process goes in both directions and I subsequently include some things from the illustrations in the text. I think, in a way, I am quite demanding because I want that the illustrator to share the same passion and enthusiasm for my story. But on the other hand, I highly value creative freedom and autonomy. I think mutual trust is essential. That is why I like to collaborate with the same illustrator more than once. Apart from that, it is important that I like the aesthetic itself, of course. I like warmth, gentleness and tender humor radiating from the illustrations.

Masa Ogrizek’s work. Photo courtesy of Masa Ogrizek.

IAB: You mix books and performance in a lovely manner – you are adding lots of theatrical references, charming details in your public performances. What do you think are the really necessary, performance tools to be used and implemented in your analogue and digital promotion, lectures and discussion to attract the attention of and interactions with young audiences and readers?

MO: I think that my work isn’t over when the book is published. I find it very important that I walk it to the readers. And I like to do it in my own inventive way, not with aggressive self-promotion. Before I became the writer I earned money by organizing creative workshops for children, so I know a lot of talented people I can use – animators, street performers, puppeteers, etc. I want to attract the attention of the young audience, that is true, but on the other hand, I don’t want to get bored. So it is a challenge to promote each book in a unique way that reflects its spirit.

Masa Ogrizek’s work. Photo courtesy of Masa Ogrizek.

IAB: Is it difficult to write for children and youth today, in the present time of lots of aggression, brutal external influences, the rising educational power of parents, and free will on the Internet?

MO: To tell you the truth, I don’t think about that when I write. I really enjoy writing; this is very special state of mind. It is very peaceful, and playful at the same time. I hope readers of my books can feel both of these while reading. The times are rough, I agree. That is why I try to put some grace and some light into my work and show young readers what the world could or should be like: full of friendship, solidarity, courage, and adventure. My books are full of bizarre characters; that is one way to fight uniformity, which is one of the consequences of consumerism despite its infinite choices.

IAB: On one occasion you stated something that holds my attention strongly – that it is better to start and develop a professional career as an author when you are an older person, a mature one with certain amounts of experience behind you, like being a parent and having a partner. Can you share more about this attitude toward starting a career at an older age?

MO: I think that one of the most important things in the creative process is authenticity. And for most of us, is quite a long journey to get there. I was always fascinated with art. Most of my friends and all of my partners were artists. I was warming up in their presence as a fan and muse before I became one of them. I began writing in my forties when I was formatted as a person. I think that is a reason that I found my own voice very quickly. As I stated before, I don’t like a didactical tone. But that doesn’t mean I don’t believe that books and art in general have educational power. I think it is very important that humanistic values are inherent in children books. And they are much more powerful if they come from personal experiences. I think young readers can feel it.

IAB: Slovenia is a very beautiful country, but also a small country. Besides the high quality of artists, it is too small a scene for a sustainable existence living only from authorship. So, you are using your artistic capacities in the domain of cartoons, comics, theater, animation; are you working across fields in an interdisciplinary way?

MO: I don’t regret that I have worked in very diverse fields in the past: as a journalist, literal critic, and coordinator of creative workshops for children. I got many experiences that way. But now that I have found my vocation, I would love to live only from my authorship. That would be my paradise. Flirting with screenwriting for animated adaptations of my books is a way of earning money, but also a way of bringing my stories to a broader audience. I am a curious person, so I enjoy learning new things. But on the other hand, I realized that I would like to devote as much time as possible to writing.

Masa Ogrizek’s work. Photo courtesy of Masa Ogrizek.

IAB: Do you think animals are more inspiring than people, Maša?

MO: No. I am fascinated by people. But some stories for children are easier told with animal characters. For example, the main character of my book Koko Dajsa is an old hen, who is constantly criticizing everybody. Since she is a hen, I didn’t have to be political correct and I could say she is old and grumpy; if she were an old lady I couldn’t do it so directly. And because different kinds of animals are so different from one another, you can exaggerate some (human) characteristics, which can be very humorous.

IAB: Recently you published your latest book Ljubo Doma (Home Sweet Home). Why write a story about house works with kitchen utensils and furniture, looking towards current trends and culminating in the mobility in art and literature, and the actual topics of changing impressions, landscapes, cities, superficial meetings with people, and fluidity in the lives of authors?

MO: It is a story of brother and sister who have to move from a big house in the countryside – where they have lived all their life with their parents and grandparents – to a small apartment in the city, because their mother got a new job there. This is quite stressful for them. This is just a frame. In the book, we learn about different types of furniture and home appliances and how they developed through history. I tried to show children that there are big differences regarding gender and social class, and that a lot has changed from the time when their grandparents were young. The “moral” of the story is that even a flat can be “home sweet home” if you share it with loved ones. I am by no means against mobility, especially (political) migrations. That would be a conservative statement. But in a way, being a homebody can have a subversive connotation in a world that praises speed and constant changes. In my opinion (tourist) traveling is, in most cases, just another form of consumerism. It is important that we open our homes – and our hearts – to different kinds of people and experiences. And if you are a homebody – and I am one of them – you have time to read.

IAB: Thank you very much dear Maša.

Skopje/Ljubljana, 2019/2020

This interview was published and conducted by Ivanka Apostolova Baskar.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Ivanka Apostolova Baskar.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.