My Stay Is Almost Done and I Don’t Belong to Anyone is the story of a desperate search for love and passion. The play’s protagonists go on a quest for le grand amour, or that failing, its substitute, in a rather peculiar setting. Happiness is to be found at a health resort facility called in these parts a sanatorium, which to the uninitiated may seem the place for long-term medical treatments, disability, and pain. In fact, the sanatorium is a parallel space-time where the protagonists who long for amorous intoxication and are game for just about anything to get it to engage in a perpetual game of wooing and romantic rivalry. The exploits of the patients of Professor Józef Dietl’s sanatorium are staged as an operetta, which means the genre is given a second life too.

My Stay has two main sections subdivided into smaller, clearly separated units that structure the play according to time and setting. The first part sees the arrival of six business people who consider investing in the upgrade of the sanatorium. In order to determine its investment value, they masquerade as patients and submit themselves to treatments such as mud baths, cryotherapy and spa water drinking under the watchful eye of the all-powerful nurse Wanda (Katarzyna Zawiślak-Dolny). Cut off from the outside world, they undergo a mental transformation. As the water in the downstage fountain babbles in a slightly dreamlike way, the emotionally aloof, profit-driven individuals gradually leave the rational world behind, abandon self-control and come out as emotional creatures. ‘That’s nothing, I suffer from melancholy.’ ‘I can feel death breathing down my back’, they confide to one another, trying, as patients often do, to out-trump each other with tales of pain and misery. After baring their frailties and realizing their loneliness and craving for human connection, they pair up and plunge into romantic adventures. The first part concludes with the intervention of the nurse, who invites the group to join in ‘geriatric exercises’. The investors-to-be dress up as old age pensioners, donning bland clothes, hairpieces, and chunky glasses to turn into quintessential sanatorium patients, a chorus of the elders.

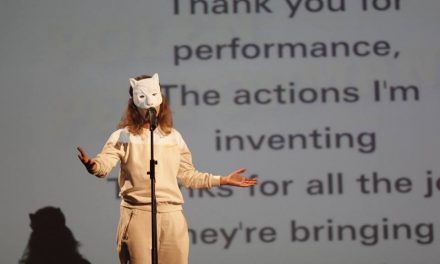

R. Szumera in Turnus, mija a ja niczyja [My Stay Is Almost Done and I Don’t Belong to Anyone]. Directed by Cezary Tomaszewski. Photo by Monika Stolarska.

The recurring leitmotif of the sanatorium operetta are lips, the body part that holds the promise of safe passion without overstepping the bounds of common decency. The scene of the ‘adoration of the lips’, inspired by the Catholic adoration of the cross, is telling ‒ Professor Dietl and the nurse hold the outstretched hands of a patient elevated on a chair, while the other patients come up and kiss him on the mouth. Meticulous about hygiene, Wanda hurries to wipe the patient’s lips with a handkerchief to make them ready for the next kisser.

Lips also figure prominently in the aria sung by Słotwinka, Kto me usta całuje ten śni [Who kisses my lips dreams], lifted from Franz Lehár’s Giuditta. The song is also conspicuous for another reason. Despite its comedy pedigree, it is tinged with sadness and its melodic line is infused with melancholy. ‘Why do each of you, / on seeing me for the first time, / when you look me in the eye, / and you feel my love, / wants to kiss my hands? / Why do swarming men keep admiring my dance? / Why do you want to know if I love you now or don’t love you yet?’, the lyrics go. Here, as a side note to the romantic adventures, the creators discreetly address the issue of the position of women in operetta, a genre that has been called ‘short-skirt muse’. Quite prominent in the show is the stereotyped presentation of its female protagonists, their objectification as trophies in male rivalry and their limited rational judgment contrasted with strong emotionality.

The inner world of the play, governed by an internal logic, resonates interestingly with its form. The creators draw copiously from operetta but at the same time distance themselves from it, e.g. through self-referential meta-comments projected upstage, which invokes the history of the genre. Things teeter on the edge of kitsch but never tip. Musically, the play can be described as a nostalgia-laden greatest hits collection with pieces by Wagner, Offenbach, Bach, and Verdi. The timeless Polish-tradition songs such as Dziewczyny z Barcelony, Brunetki, blondynki, Co się dzieje, oszaleję or Upływa szybko czas [Barcelona Girls; Brunettes, blondes; What’s happening to me? Am I going crazy?; Time flies fast] draw the strongest response from the audience. However, the scene of the evening dance, which blends feasting and disco-polo, as well as Stanisław’s showpiece, the ‘famous pasodoble’, provides a truly Polish-style musical culmination.

D. Malchar, K. Zawiślak-Dolny, L. Bogacz in Turnus, mija a ja niczyja [My Stay Is Almost Done and I Don’t Belong to Anyone]. Directed by Cezary Tomaszewski. Photo by Monika Stolarska.

‘I love operetta for its heavenly forgetfulness and divine idiocy’, wrote Witold Gombrowicz, who was quoted more than once after the premiere of the sanatorium operetta. In Cezary Tomaszewski’s show ‘heavenly forgetfulness and divine idiocy’ become a catalyst for reflection on the plight of the elderly and sick and their daily life, especially its emotional and sexual aspects. Patients are referred to sanatoriums due to their failing bodies but head there in the hope of finding a cure for their loneliness or at least forgetting about it for a moment. They want to move for a while into a parallel universe where anything is possible, above all love, even though they are well aware that nothing lasts forever, their sanatorium stay will be soon over and their loneliness is going to hit back with a vengeance, so a sanatorium operetta can never be wholly joyful.

Juliusz Słowacki Theatre in Kraków, Turnus mija, a ja niczyja. Operetka sanatoryjna. [My Stay Is Almost Done and I Don’t Belong To Anyone: A Sanatorium Operetta]

Directed by Cezary Tomaszewski; written by Iga Gańczarczyk and Daria Kubisiak; music by Cezary Tomaszewski; music supervisor Weronika Krówka; stage and costume design by Bracia (Agnieszka Klepacka, Maciej Chorąży); lights by Jędrzej Jęcikowski; premiered on 12 April 2019.

This article was originally published in Polish by Didaskalia. Theater Journal 2019, no. 153. It was translated into English by Didaskalia and TheTheatreTimes.com and reposted with permission. The translation was supported by Polonia Aid Foundation Trust.

Didaskalia is now an open-access journal. The frequency remains unchanged and they will continue to appear bimonthly.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Natalia Brajner.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.