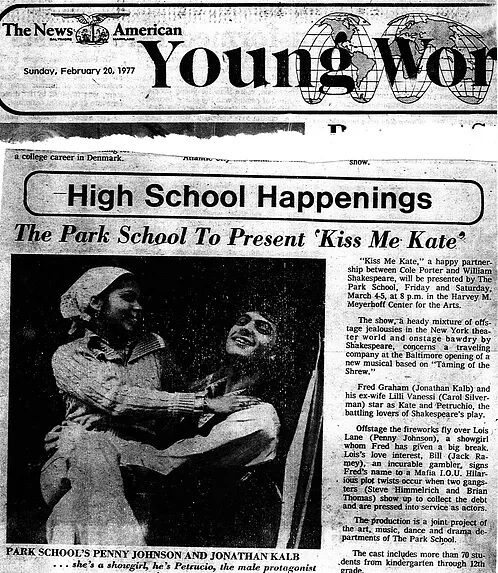

In the winter of 1977, at age 17, I played Petruchio/Fred Graham in a Kiss Me, Kate production at my high school in suburban Baltimore. It’s a crazy thing, but I loved this show from a very early age. That’s because, about six or seven years earlier, I’d watched my father play Petruchio/Fred Graham in a community theater production of the show in the New Jersey town where we lived at that time.

Since seeing my father perform, I’d played the original cast album a hundred thousand times on our phonograph, electrified by the bounce and wacky inventiveness of the Cole Porter songs, not to mention the sexy innuendo of their lyrics, which I only dimly understood. I learned about locker room talk as much from Kiss Me, Kate as from actual locker rooms.

This is a rather singular situation, I know. Not many families treat the vain, blustering, patriarchally preening role of Petruchio as a hereditary occupation, let alone a masculine rite of passage. Mine did. Or half of it did.

I have only fuzzy memories of my father’s brash and buoyant performance. I always thought he was a strong and intelligent amateur actor, even when I grew old enough to know a hawk from a handsaw. What I vividly remember is how my mother, a schoolteacher with a Ph.D., hated his doing that play. She’d savored and celebrated his other roles—particularly the King in The King And I—but the weeks he spent devoted to Kiss Me, Kate were tense and unhappy. To my young eye, it looked like a lot of inexplicable bristling and stomping around the house.

By the time I played Petruchio my parents were separated. My mother had moved back to New Jersey and I’d stayed with my dad—it was a “men’s house.” The obligation to see my show forced my mother’s first return to Baltimore since she’d fled. Once again, I remember her reaction more vividly than the show itself.

All young actors try on the attitudes and behaviors of their roles in their real lives, and for weeks I’d been gadding about like the puffed up peacock I took Petruchio to be, mansplaining and making rumbustious and facetious remarks about spanking, walloping, and womanizing. Some people laughed. It was all just innocent fun, right?

When my mother saw this behavior she blew a gasket. She would have thrown pans and crockery if she had a kitchen handy. There was no point in telling her that the play was making fun of such boorishness and so was I. She knew the play. Seeing me experiment with that gender-role was unbearable to her. At the show, she sat in the second row, never smiled, gave me a bristly hug afterward, and drove back to New Jersey.

Photo: Joan Marcus

Among the clearer lessons of that experience, for me, was the knowledge that, for all its popularity, Kiss Me, Kate has some ferocious enemies. It’s never been merely a romp or a simple love letter to showbiz. It’s always been (like its source play, Shakespeare’s Taming Of The Shrew) also a velvety face-slap that invites the masses to yuck it up collectively, for the millionth time, over all the hoary lowbrow japes about “broads,” “dainty debbies,” “bags” and “kicks” (in the Coriolanus). This just has never been funny to everyone.

Now, I will admit that I still giggle at this show, and not just out of nostalgia. Moreover, I think Shakespeare’s Shrew is playable in the right hands, even for woke audiences in an age fed up with the likes of Harvey Weinstein. I worked as dramaturg on a good example: the 2012 Theatre for a New Audience Shrew directed by Arin Arbus, in which Maggie Siff and Andy Grotelueschen played Kate and Petruchio as intelligent misfits who miraculously found each other in a dimwitted, cartoon-Western world that had treated them both like Martians.

The key in both cases—Kate and Shrew—seems to me the same. The audience has to be made to believe that the lead couple is really in love. That’s the only way to make all the crude gender stereotypes and jokey misogyny seem tactical rather than embarrassing.

When Kiss Me, Kate returned to Broadway in 1999, starring Brian Stokes Mitchell and the late Marin Mazzie, I did believe they were in love. Mitchell and Mazzie cleverly located crucial breather moments in the mad bustle of the opening scenes that plausibly suggested a fiery core of buried sincerity beneath all their bickering.

The truth is, Sam and Bella Spewack’s book for Kiss Me, Kate is no dramaturgical triumph. Its love setup is downright flimsy. The actors of Fred Graham and Lilli Vanessi (Petruchio and Kate) have to conjure all the magic of a divorced couple’s banked fire for each other out of a few nostalgic lines about bygone road tours and a keepsake champagne cork, followed by the inane duet Wunderbar. If they can’t seal the emotional deal in those few busy minutes, then So In Love, which immediately follows, can’t infect us with longing to see Lilli get what she wants, no matter how magnificently her voice soars.

Scott Ellis’s new Kiss Me, Kate at Studio 54 is smart and bright and rollicking. There’s some splendid fresh choreography in it (Why Can’t You Behave, Too Darn Hot), and its stars, Kelli O’Hara and Will Chase, both have world-class voices and charm galore. What they don’t have, alas, is plausible chemistry as Fred and Lilli. Yes, they can belt. O’Hara’s rendition of So In Love is so powerful it almost manages to substitute for chemistry. When it’s over, though, both actors revert to relying on the brittle archness of the Spewack dialogue, which doesn’t contain any heat of its own, and they end up looking like stereotypes. That’s the chief reason why the audience can’t just lighten up and ignore the clank of skirt-chasing jokes in the #MeToo era. Politics rushes in to fill the space that love abandons.

Photo: Joan Marcus

Interestingly enough, the snappiest number in the new show is the anthem to Bianca/Lois Lane’s marital availability, Tom, Dick, Or Harry. David Chase’s acrobatic, pelvic-thrusting choreography is hilarious, and performed with cool circus panache by Corbin Bleu, Rick Faugno, and Will Burton, manically orbiting and pulsating around the delightfully ditzy Stephanie Styles as Lois. Like Lois’s Act 2 number Always True To You In My Fashion, Tom, Dick, Or Harry is a salute to female sexual agency and freedom, and in this production salutes often have to stand in for ardor.

Women are duly given the floor and the mic, even the upper hand in fighting—O’Hara’s Lilli/Kate kicks Fred/Petruchio so savagely and relentlessly it starts too seem like assault. The lyrics to Kate’s concluding song—originally borrowed from Shakespeare’s forever problematic “I am ashamed that women are so simple” speech—have been altered so that “people” are now simple and respect and loyalty are owed to “mates” rather than “husbands.” It’s all nicely PC. It just feels a little dry and safe. We need another reason to indulge one more time in this tricky old Cole Porter confection, and that reason has to be love.

Music and lyrics by Cole Porter

Book by Sam and Bella Spewack

Directed by Scott Ellis

Studio 54

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Jonathan Kalb.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.