The Maids, September 29-October 23, The INTAR Theatre, New York City

Invoking the semi-mythological ancient Greek seer Epimenides in his introduction to the published text of Jean Genet’s The Maids, Jean-Paul Sartre reminds us of the famous paradox of self-referentiality: “Epimenides says that Cretans are liars. But he is a Cretan. Therefore he lies. Therefore Cretans are not liars. Therefore, he speaks the truth. Therefore, Cretans are liars. Therefore, he lies, etc.”

As in Genet’s plays, those theatrical halls of mirrors, Epimenides’ paradox prompts a crisis of logic and a skepticism regarding appearances and knowledge. Born in Paris in 1910, Genet was an orphan, a criminal, and a gay man who spent much of his youth incarcerated before becoming a poet, novelist, and political activist. He turned dramatist, Sartre says, “because the falsehood of the stage is the most manifest and fascinating of all.” Genet’s overdetermined status as a perpetual outsider made him acutely aware of the ways in which both the “other” and the “self” are fictions, reciprocally propped up like so much flimsy scenery.

The Maids unfolds over the course of an evening as two domestics engage in a variety of increasingly lethal sadomasochistic role-playing games. Solange plays her sister Claire. Claire plays their mistress (Madame), whom they both love and loathe. This is not the first night they have elaborately fantasized about murdering their employer while awaiting her homecoming, but it is the first night they succeed in working through their burlesque of domination and submission efficiently enough to traverse the fantasy.

But efficiency is not exactly the operating principle of this demented, dialectical dance. Genet is coy about disclosing the rules of theatrical engagement, letting spectators very gradually arrive at the realization that what is transpiring before them is only a representation of reality insofar as “reality” is a manifestation of unconscious aggressive and self-destructive impulses. The play thematizes and revels in its own extravagant theatricality, demonstrating the ways in which insistent artifice (in the theater, as in life) can occasionally serve as the surest path to authenticity.

In a timely co-production by the INTAR Theater and One-Eighth Theater, José Rivera has adapted Genet’s metatheatrical fable of ontological violence to address the very real plight of his native Puerto Rico. As an unincorporated US territory, the island continues to exist in an absurd in-between state of disenfranchisement. Citizens are not permitted to vote in presidential elections or send voting representatives to Washington, even though Congress has legislative authority over everything from the Puerto Rican postal service to healthcare to military defense. An astute critic of the psychological consequences of French colonialism during his lifetime, Genet would doubtless have approved of his play being transposed to Vieques in 1941, the year the US Navy invaded and occupied the island. Rivera is perhaps best-known as the author of Marisol, his 1993 apocalyptic elegy for the dispossessed and internally riven immigrant communities of New York City. In his version of The Maids, Rivera chooses to call his maids not Solange and Claire, but Monique and Yvette, the first names of the actresses who originated the roles in the 1947 Louis Jouvet production at the Théâtre Athénée in Paris, perhaps in a gesture of solidarity with the theatrical laborers who made it possible for the piece to come to life in the first place, perhaps to call attention to the complicated power relationships undergirding so many of the most important theatrical collaborations (Monique Mélinand was Jouvet’s student and then mistress at the time The Maids premiered), perhaps only to enhance the self-conscious deceitfulness shrouding every aspect of the piece.

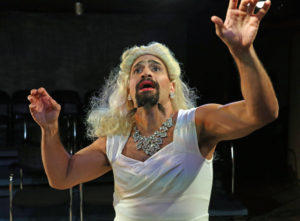

Daniel Izarray in The Maids. Photo credit Carol Rosegg.

Appropriate as the latter rationale might be, it is brilliantly nullified by director Daniel Irizarry’s antic production, which never allows us to forget that what we are witnessing is a representation brought into being through considerable effort. Rivera’s adaptation doubles down on the disorientation by dividing the text between two same-sex couples of siblings/lovers, one male, one female, each couple consisting of an actor of color appearing opposite a white actor. As we approach the denouement, all four appear on stage together, trading partners and roles in an exquisitely choreographed danse macabre involving abrupt, frame-breaking, disco-flavored lighting shifts, manic waltz and Charleston routines, performers climbing like coked-up sloths across the ceiling, copious amounts of glitter being flung into the faces of the audience, and performers spitting on each other or into the air only to catch the projectiles in their own mouths. The whole spectacle is at once sexy and repulsive, analytical and deranged. These maids lurch back and forth between clamoring “No honor without independence!” and confessing to “counterrevolutionary lust for my oppressor.” Preshow business at the performance I attended involved one of our Moniques assiduously scurrying about the intimate playing space, at one point lifting up my companion’s shoe to polish it with a rag, then pushing the hem of my dress aside to crawl under my chair in search of some hard to reach dirty spot. Beginning the show by putting these servile bodies literally at our feet (and between our legs) sets the tone for the evening of intimately entwined abasement and eroticism.

In Genet’s Our Lady of the Flowers he writes “If I were to have a play put on in which women had roles, I would demand that these roles be performed by adolescent boys.” Sartre tells us that while “one might be attempted to explain this demand by Genet’s taste for young boys…the truth of the matter is that Genet wishes from the very start to strike at the root of the apparent…In order to achieve this absolute state of artifice, the fist thing to do is to eliminate nature. The roughness of a breaking voice, the dry hardness of male muscles and the bluish luster of a budding beard will make the de-feminized and spiritualized female appear as an invention of man, as a pale and wasting shadow which cannot sustain itself unaided, as the evanescent result of an extreme and momentary exertion, as the impossible dream of man in a world without women.” While it makes a kind of sense that someone of one gender might be able to portray someone of the “opposite” gender with more perspective and perspicacity than someone of the gender being portrayed, historically this logic has often resulted in men playing or parodying women’s roles, without women being permitted to return the favor. This imbalance is, to an extent, replicated in this production, with the eventual entrance of Madame (La Doña in Rivera’s adaptation) being played by a third man in drag (Mr. Izarry, in a long, preposterous blonde wig, hairy chest, and unapologetically baroque facial hair).

But the confounding love of the oppressed for her oppressor and vice-versa is not gender-specific. Nor is the relationship between colonizer and colonial subject a one way street. The insider needs the outsider to stay outside in order to remain legitimate. The master needs the slave. In 1898, when the United States was wresting possession of the territory from Spain, Republican Joseph Foraker argued on the Senate floor that Puerto Rico “differs radically from any other people for whom we have legislated previously…They have no experience which would qualify them for the great work of government.” This paternalistic attitude has not stopped the US government from using the island as a tax haven to stall an exodus of American businesses, then rescinding tax breaks in order to offset the damage done by our most recent recession. This has resulted in the current 45% poverty rate in Puerto Rico and widespread shutdowns of schools and other essential services. No plan for a “bailout” that might have any proportionate impact on the current crisis has been seriously entertained. A certain “Don Pedro,” presumably the then-imprisoned Pedro Albizu Campos, leader of the Puerto Rican independence movement is repeatedly invoked to as a potential savior of the people, but the more enduring question this production raises is whether the people, any people, really want to be saved, or whether freedom and constraint aren’t in fact two sides of the same coin.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Jessica Rizzo.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.