It’s been six years since Leper and Chip played to sold-out Dublin audiences with critical success. Not bad for first-time playwright and Dublin native Lee Coffey. His next two plays, Peruvian Voodoo and Slice, The Thief continued to explore complicated, young Dubliners who are forged from dark and traumatic circumstances.

In 2018, the Chief Executive of Dublin Port, Eamonn O’Reilly, commissioned Coffey to create a piece for their Port Perspectives initiative. After a year of research, reading about the history of the docks, interviewing dockers, and looking into his own family history in the tenement slums of Dublin, Coffey created a story spanning three generations over 100 years called In Our Veins. The show was another hit.

This successful relationship led to O’Reilly reaching out to Coffey again to see if he’d be interested in filming Leper and Chip and Slice, the Thief for their “Pumphouse Presents” series which is being presented with Axis Ballymun. Coffey immediately said yes even though he knew these plays would have to be reimagined for film.

It’s also a bittersweet moment for Coffey. Beloved actor and director Karl Shiels is responsible for Coffey’s first big break – he immediately loved Leper and Chip when he first read it and put it on through his company Theatre Upstairs. He, unfortunately, passed away last year, so Coffey is dedicating the filmed productions to him. Writing the dedication, said Coffey, was the hardest part about revisiting these plays.

The following is an edited and condensed version of our conversation.

Ashley Steed: Let’s go back in time a little bit, six years ago. What was your initial inspiration for Leper and Chip?

Playwright Lee Coffey.

Lee Coffey: I wanted to act, [but] I didn’t know what I wanted to do. I was really enjoying scriptwriting and I’d written a short story for a class that I had to do. I just happened to write it like a script because I was trained as an actor – I read so many scripts. I said, “I want to give this a try.” That was literally my initial idea. I said, “I’m just gonna give it a try, write a play.” Well, okay. What about a boy and a girl, and they meet at a party? That was my initial jumping-off point. In Dubin, everybody has a nickname. I knew a lad growing up called Leper. So I said, well, who do I know? Leper, that’s a good one, and he burns his leg in a fire and that’s why they call him a leper. And my auntie’s name was Chip, and she had really bad teeth as a kid so I decided to call [the character] that.

I just started to write the script, and I wrote the first two sections which is a house party where they meet and initially they’re enemies on opposite sides of this rift. Then afterward, I would leave myself dramaturgical notes as to where I thought it was gonna go at that particular point. Then I’d walk or go away and come back to it, read from the beginning of the play onwards, and continue.

The structure of it is a duologue-monologue play. So generally it’s Leper and Chip together and separate and together and separate – structurally that works really well, but I’m not gonna sit here and say I knew what I was doing at that particular point of writing that. I knew I had to split them up to make it interesting for an audience, I didn’t know much but I knew that. I [then came] up with really off the wall elaborate stories of where they go and their day just keeps getting worse and worse until eventually, they come back together. It’s a roller coaster, it’s really inappropriate, it’s visceral. I would know Leper and Chip, I know characters like that growing up in Dublin.

AS: I was going to ask that, do you know these [characters in real life], especially because everybody talks about how the writing is fast-paced and energetic, and I feel like to write something like that you really need to know people who speak like that.

LC: I didn’t have to research the play. Now, I would never just go to the page without knowing what I want to write, I would put extensive amounts of research in. But that’s with experience. As you go on, you want to deal with bigger and broader topics which means you have to [do] research. But at the time, I just wrote what I knew and I grew up with characters like this. A lot of the stories in the play come from either my own life experiences I’ve had or experiences my friends have had.

It’s fast-paced because I wrote on the Luas [the tram in Dublin] and so I was always on the move. [The play is] carried by the pace of it. If it’s performed in any other way, it doesn’t work. You can’t sit there and take your time with a play like this, it has to be performed Helter Skelter. Boom, boom, boom. I’m also a drummer, I’ve been playing music for years. So I didn’t always [think about pace] at the time, but that inherently came through in the script.

AS: Being a drummer makes so much sense, […] being a writer with that skill of tempo and beat and pace – of course, that’s only going to help the words come to life.

LC: It’s, again, it was something that I never really knew I put into my writing until it happened.

AS: I know with your first three plays, they are more direct address… more intersecting monologue in style and so I was wondering if you did that purposefully or if it was kind of trial and error [rather than writing traditional dialogue].

LC: I did it purposely. The Irish, we’re known for storytelling and we’re known for that type of [direct address or monologue] theatre, and just, in general, were natural storytellers. I found it really natural to me to write it in that way. I never played around with traditional dialogue or traditional scenes. I knew I wanted it to be out to the audience, and that was it. In the script, they never actually touched each other. Leper and Chip never looked at each other, they never touched. Then as we went on in rehearsals we have one moment where they do directly address each other and in that moment it’s always interesting to watch an audience because they are kind of thrown off – it jars with them in the best possible way. They never feel, “Why are they talking to each other as a normal play”, but they just say, “ahh they’re talking to each other, they finally they look at each other”, because other than that it’s sly little glances, they’re always aware that the other is in the same space, but it’s always from their perspective. And they always play with the internal and the external, which gives us some beautiful comedic moments because he says what he feels, [where] what she’s actually feeling is something completely different which undercuts what he’s doing, and vice versa. And even that then helps for the dramatic moments of the play, because you can tell what he’s thinking, but she thinks she’s thinking one thing but he’s actually taking something completely different. And that breaks your heart because we hear and see the internal and the external, so we know what each of them wants to do, but they don’t know what the other character wants to do. We’re constantly informing the audience and kind of hiding that knowledge from the other character. I just love that style of theatre.

I love direct address. I love the immediacy of theatre. I love trying to do what film can’t really, in my opinion. I think it makes it more personal, if you can drop a particular line on an audience member it’s kind of like, that’s their line. I think it’s something that we can do as theatremakers that film can’t do.

AS: It’s going to be interesting, then, to see how that [direct address] translates to being filmed. I do want to delve more into adapting [these plays] for film, but before we do that, I want to get to Slice, the Thief which is the third play in your Dublin Trilogy. Did you think when you first were first writing Leper and Chip, “oh maybe I should, you know, do this in threes” or was it after the success of [the play] you were like, “oh shit I gotta do more of this”?

LC: That’s exactly what I had [thought]! I had written one play. Karl Shiels, my dear friend and the director of [Lepper and Chip], who sadly passed away last year, he was introducing me to all these people not as a new writer, but as a writer, as a playwright. He said, “so what’s next?”

I wrote a play called Angels of Mercy, and we had a reading the Wednesday after Leper and Chip finished and it was awful. [He laughs] It was because […] I wrote it the way somebody else would write a play. Everyone kept saying, “what’s your voice? What’s your voice?” and I didn’t know what they meant.

There was one section in the middle that was written like Leper and Chip – it was the section that I loved and also the section at the reading that everybody said, “that’s the play. The rest of it, get rid of it.”

I realized that [that section was] my voice and that’s my style. And that’s what I do. After that I was just, I don’t think there was anything stopping me. I went in and wrote Peruvian Voodoo, which was the second play. I think I wrote that in three weeks. I had this clear idea and I knew how I wanted to write it. I attacked that script. I’d written Slice before Peruvian Voodoo. But I hadn’t finished it because I hit a wall, and I didn’t know how to end the play [Slice]. So I left it and wrote Peruvian Voodoo.

Then I was playing a video game – you know when you’re playing a video game and you reach one point and you think you’re done and then you have to go and do something else? So it was just… a light went off and I said he never resolves what’s [happened to him]… that he never gets out of this. I went straight back and I finished the play in a couple of days because I knew what I wanted to do. [Before], I was trying to tie it all up in a nice little bow. And that’s not what life is. That’s not what that story is. So it kind of just happened organically. Then I had this idea because the three of them were similar in style. They’re quite visceral, they’re very fast-paced and there’s a beautiful rhythm in each of them. They’re relentless. They just kind of naturally blended into a trilogy.

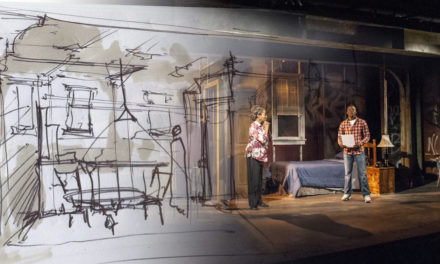

Slice the Thief by Lee Coffey. Performed by John Cronin. Directed by Aaron Monaghan. Photo by Dan Dalton

AS: Have you adapted either script at all or made any revisions to them?

LC: Yeah, we have. Myself and Laura [Honan the co-director] looked at Leper and Chip and there’s a couple of sections that we needed to clean, just because the transitions wouldn’t have worked as well on screen as they would in the theatre. We pretty much looked at the whole script with a fine-tooth comb. We weren’t just going to go through this again and say, “we’re going to do the exact same production that we did six years ago” because we’re all older and so much has happened in each of our lives, collectively as a group and also individually, artistically, and personally. So I think we took all of that into the play.

We also played around with the direct address. So most of it there’s kind of a voyeuristic element to the production, which I’m really, really happy with.

With Slice, I adapted it a lot more. Previously Slice was played by Wesley Doyle who was brilliant, but was 22, I think, when he played it. I don’t want to give anything away, but the way Slice ends is pretty horrific and it’s pretty tragic. At the end of Slice, you always left with the sense that everything was going to be okay – so what I did was I flipped the age of the character. I got John [Cronin] who is in his 40s. What happens [then] if we approach the script where Slice is now 20 years older than he previously was in the last rendition. Obviously, that means a lot of the script has to change. But we found a nice language between present and past Slices, which is what we’re calling them. I wrote a prologue which is where he is now [at 40]. Then what we do is we go back to the beginning of Slice 20 years ago and we follow his story when he was younger. We start to feel that in certain moments where he references the future or what might happen, you can see that he’s aware of it. And you can see the residuals, and you can just see that he knows what’s going to happen – it’s almost him putting his hand around his past younger Slice and saying, “you idiot,” is the way we kind of approached the play, like he was the father figure of his previous self. When we get to the end of the play, you fully believe that 20 years have passed and this man is tortured, whereas before you didn’t; he was kind of this happy go lucky character, that everything’s gonna be fine [when it’s not].

AS: So how are you feeling about the two filmed versions?

LC: Really good, really, really good. I honestly think we’ve created something really special.

With everything that’s going on this year… The festival and the different artists that the Port put together, I think it’s a lovely gift. It’s been such a horrific year for everybody. None more so than artists. It’s been a tough, tough year we’ve just seen our whole sector decimated, as many other sectors have, but you can only look at it from where you are. The fact that Dublin Port gave us a chance to all work together. These plays weren’t, possibly, ever gonna come back, but all of a sudden we got to collaborate on them again.

We got to reimagine them, we got to play, we got to work. We got to adapt them for screen. And we got to find a gorgeous language between film and theatre. John Cronin put it really well. He said, “we’re trying to capture the immediacy of theatre with the stillness of film.”

AS: I’ve got a couple of questions for you about Covid because, you know, we really have to talk about this moment in time. I’m curious, were you working on anything or getting ready to open anything when Covid hit?

LC: Luckily enough, I didn’t have any shows scheduled for this year. I was in development [of a new play with Axis Ballymun].

A lot of my friends had shows canceled and your heart just bleeds, because we all know how much it takes to put on a piece of theatre.

AS: It’s a little different for you because you’re a playwright so playwrights tend to be kind of alone in their holes writing – has this pandemic affected your creativity at all?

LC: It really has. I love isolation, that’s where I’m at my best. But I never ever thought that isolation would hurt me so much, but I think it’s because it wasn’t by choice.

I just couldn’t do anything. I finished Good Orderly Direction [the play that was being developed when Covid hit]. I finished off the script because I think the creative juices were still flowing from being in the room [in preparation for a public reading]. Then once the Covid really kicked in and lock down came, I didn’t do anything. I could not work. I just don’t find this situation conducive to creating work. People will come out and say, “oh, I’d say you have four or five plays now” or “you need to have a play coming out of this.” A couple of weeks in, I realized I don’t and I stopped kind of beating myself up over that and I just learned to relax and enjoy myself. I started to work on myself. I started to exercise more and eat better, and I started to do all the stuff I hadn’t previously done. Because when you work in theatre you’re always on the go, you always have something that needs to be done.

I spoke to a lot of my fellow artists who are all beating themselves up because we all feel we need to be productive. But why, why can’t we just exist? And I think we have a real problem with that as artists, we always feel like we need to be doing something. And if we’re not being creative, it really messes with our minds.

Then this project [with the Dublin Port] presented itself. I started to work on this and I then started to edit old work, which was my way of getting back into it because I wasn’t creating anything from scratch. I was just working at honing previous scripts I had. So I found that was a good way in. But seriously, I’ve really, really struggled with the Covid

AS: So, then, what have you learned from this time and hope to carry forward?

LC: Professionally, I’ve learned to not be so hard on myself. I think that’s a major one I’m going to take away from this. That it’s okay not to be okay. It’s okay to struggle at certain times. And it’s okay that you’re not working on a particular project at the moment. It doesn’t mean you don’t have projects or projects are not going to come. But don’t beat yourself up because you just want to go on a walk and then sit watching TV all day. That’s okay. Whatever helps you. Whatever makes you happy.

Life is short and at any moment it can be taken away. Obviously taken away in the sense that you [could] die, but also could be taken away in the sense that you can’t see anybody you love. You can’t go and give a hug to anybody who you love. You can’t go and sit in the same room. You can’t be in their presence. You can’t listen to their stories, when it’s not over a fucking zoom. That’s what I’m going to take forward, not to be so hard and enjoy my life, whether it be artistically or personally.

Leper and Chip and Slice, the Thief are part of a Winter Festival of Plays presented by Dublin Port Company.

Five plays were filmed in the beautiful Pumphouse Building in Dublin Port during the Summer of 2020 they will now be premiered online over five Friday Nights culminating in a week-long festival of theatre in December 2020.

These shows will be available free of charge as a gift from Dublin Port in these strange times. But donations will be accepted towards a new artist development fund to be managed by axis Ballymun.

For more information and to reserve tickets please visit Axis Ballymun: axisballymun.ticketsolve.com/shows

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Ashley Steed.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.