Subdued browns, grays and black dominate the stage. The impression of a vast empty space is amplified by the clocks dotted around the stage. They stand on the floor, creep into the scenery and costumes, hang from the ceiling and from the dwarf tree redolent of Salvador Dali’s work. The two-level scenic space is pulled out from the darkness by masterfully controlled light. Downstage, on movable tables, puppets will be animated amid changing scenery; to the right, there is a platform that supports an interior resembling a watchmaker’s workshop, with a huge bookcase, a big wooden desk, a comfortably worn armchair, and a raft of old-fashioned clocks. The largest clock is suspended under a big spherical skylight, its transparent glass revealing a cityscape bathed in daylight. The view behind the glass seems unreal in the dark.

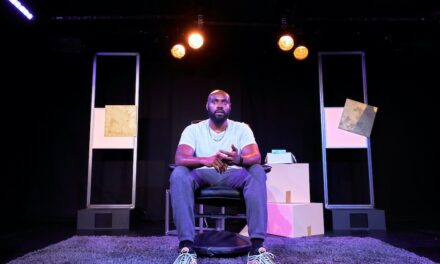

Wielkie mi coś [Big Deal] written and directed by Marta Guśniowska. Photo by Grzegorz Gajos.

With the moon absent from the sky, the world is thrown out of balance: the tides disappear, wolves have nothing to howl at, lovers can’t go on moonlit dates. Pistachio (animated by Tomasz Szczygielski) can neither spit out nor sneeze out the moon. The embarrassed elephant takes “good advice” and “runs where pepper grows” (a Polish idiom roughly equivalent in meaning to the English “go running for the hills”). Pepper, which makes you sneeze, will perhaps come in useful. The elephant is followed by a young wolf, Esa (Krzysztof Jarota), who cannot howl to the moon to mark his initiation into adulthood and allow him to get in touch with his parents (Esa believes that they went to the moon after they died). Racked by guilt and moved by affection for the young wolf, Pistachio, who cannot manage a single sneeze, even when cold or scared, and with no pepper on hand, agrees to burst from the inside out. But as Pistachio makes renewed attempts to do that, Esa realizes that he cares more about his new friend than he does about the moon, and protects him from being ripped apart by the Eldest Wolves (Agnieszka Zyskowska-Biskup, Zygmunt Babiak, Andrzej Szymański), who, by the way, are very amiable creatures. In the play’s end, Guśniowska resolves the plot in a romantic dénouement (as she did in her directorial debut, A niech to gęś kopnie!): Pistachio finally sneezes out the moon during his date with Miss Elephant. He can do this because the new moon comes up.

Wielkie mi coś [Big Deal] written and directed by Marta Guśniowska. Photo by Grzegorz Gajos.

Wielkie mi coś is a witty tale about friendship, love, and life goals, which are not so elusive as it might seem. Using fairy-tale motifs and the topos of travel, Guśniowska challenges not only the stereotypical image of animals entrenched in animistic phraseology but also social stereotypes: the wolf is not so scary as it is usually made out to be, and the hyena laughs not because it is mean but because it is a comedian. e There is no moralizing, no black and white and no ready-made formula for happiness.

Wielkie mi coś [Big Deal] written and directed by Marta Guśniowska. Photo by Grzegorz Gajos.

Guśniowska warns in the play’s description:

“We may sometimes feel that we don’t amount to much and we compare ourselves with others who do more or have more. The truth is that each of us has an equally important role to play in the world. Everyone is here ‘for a reason’ and our job is to find that ‘reason’”.

The process of discovery starts with interpreting the title of the play. The expression “wielkie mi coś” [“big deal”] can be used to stress that the thing in question is not important, even though our interlocutor might believe otherwise. The same words spoken with a different intonation though, have the opposite meaning. This play with language also works at a metatheatrical level ‒ before watching the show we read the title in line with its commonly used meaning, but when the play is over the literal understanding of the phrase comes to the fore.

Wielkie mi coś [Big Deal] written and directed by Marta Guśniowska. Photo by Grzegorz Gajos.

Marta Guśniowska’s play is an example of a practice prevalent in Polish puppet theatres, that is, building a repertoire by first choosing texts. The play (2019) was commissioned by Opolski Teatr Lalek (Opole Puppet Theater), whose actors feel eminently at home with Guśniowska’s linguistic style. Once again, the author has produced a successful puppet-based play drawing on similar stage design ideas. In most of her plays, Guśniowska makes it clear in her stage directions that she writes lines with puppets in mind. In Wielkie mi coś, Krzysztof Jarota, who animates Esa the Wolf with a comic flair, slips into a mixed style from time to time, building a relationship with his character, while Łukasz Bugowski as the Smallest Seed of Sand and Andrzej Mikosz as the Narrator perform as live actors, but these are exceptions proving the rule that, as far as children’s theatre is concerned, Guśniowska is mostly interested in puppet shows, both as director and playwright.

At the end of the show, the old Turtle is visited by Death, but he refuses to die before seeing his great-great-grandchild hatch from his egg. Death, who is not presented as a terrible figure but one that feels responsible for keeping the universe in order, is unrelenting. Faced with Death, all of us are equal as everyone’s life is measured by sand trickling through his hourglass. In Marcin Pawełczak’s video projection, Edgar/Bugowski stops in the narrowing of the neck of the old Turtle’s hourglass plugging it with his body, and in this way fulfills the destiny of the grain of sand. The small turtle breaks through the housing of the clock from which it hatches, and its gaze crosses with the old Turtle’s. The mood of this scene, which features beautiful, very realistic puppets and Piotr Klimek’s atmospheric music, was one of the most intimate I have experienced in the theatre. “To move somebody is probably the most difficult thing to do in the theatre”, believes the author of Wielkie mi coś. With a tear welling in my eye at the end of the Opole performance, I agreed.

Wielkie mi coś [Big Deal] written and directed by Marta Guśniowska. Photo by Grzegorz Gajos.

Written and directed by Marta Guśniowska; stage design by Pavel Hubička; music by Piotr Klimek; video projections by Marcin Pawełczak

Premiered on 15 February 2020

This article was originally published in Polish by Didaskalia. Theater Journal 2020, no. 157/158. It was translated into English by Didaskalia and TheTheatreTimes.com and reposted with permission. The translation was supported by Polonia Aid Foundation Trust.

Didaskalia is now an open-access journal. The frequency remains unchanged and they will continue to appear bimonthly.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Katarzyna Lemańska.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.