During summer 2019, Villa Bardini in Florence was the home of A Passi Di Danza. Isadora Duncan e le Arti Figurative in Italia Tra Ottocento e Avanguardia, an exhibition dedicated to the American dancer Isadora Duncan (1877-1927) and her influence upon the figurative artists in Italy. Following the example of A Living Sculpture (Musee Bourdelle in Paris, 2009), an exhibition dedicated to the work that Duncan produced during the years that she spent in France, A Passi di Danza concentrates on the period that she resided in Italy while performing in major cities such as Trieste, Venice, Rome, Rimini, and Florence. A total of approximately 170 works of art and documents that are exposed in the rooms of Villa Bardini testify Duncan’s influential role in the work of a number of Italian artists who found inspiration in her Free dance.

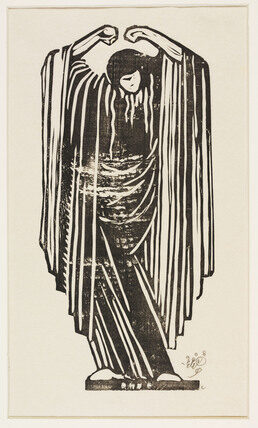

Dancer (1908) by Edward Gordon Graig. Xylography on paper.

Regarding her contribution to the world of Western Theatre Dance, Duncan — one of the key figures of Early Modern Dance — strived to liberate the dancing body by negating the academic tradition of Classical and Romantic Ballet. She looked for the human dimension of the moving body by emphasizing the expression of emotions through individualized movements that were disconnected from the rigid codes and the disciplined movement vocabulary of ballet. Getting rid of the ballet costume and replacing it with transparent veils or tunics was important towards this dimension as well; she opposed any kind of body deformation, including the use of corsets that women used in everyday life in response to the imposed ideal of the female body (small-wasted and S-curved silhouettes). Her pedagogical point of view was of great significance as well, opening paths for the establishment of educational approaches on creativity and imagination that could be trained through movement improvisation and modes of self-expression. Placing her art in the context of the revival of the Ancient Greek ideal about nature, freedom and beauty — that was eminent in the turning of the 20th century in Europe and the United States –, Duncan managed to legitimize the nudity of the female body and render Free dance a form of ‘high and noble art’ with spiritual and moral values.

Challenging through progressive ideas the norms of the female dress-code and social conduct and offering a non-sexual view of the naked body, proposing new pedagogical concepts for training in dance (as seen in her seminal essay The Dancer of the Future, 1928) and promoting free movement during an era that at the aftermath of the industrial revolution was trying to push for organized massive production justify her as a leading figure equally important to the world of Dance as well as to the realm of social innovation.

During the time of Duncan’s transition from the United States to Europe, she begins to frequent the spaces (haunts) of visual artists by performing outdoors or in ballrooms, concert halls and the salons of expensive European apartments belonging to the aristocrats who used to join together the artistic intelligentsia of the time. This is where artists from the world of visual art had the chance to get exposed to her work which becomes the main focus of this exhibition: the direct exchanges between Duncan’s dance and the work of visual artists at the beginning of the 20th century in Italy.

It is worth mentioning here that Duncan is a very particular case in which the concepts and ideas she finds in art — especially that of Ancient Greece and the Italian Renaissance (as for instance in La Primavera of Botticelli) — are being explored in movement and in turn these ideas are found and represented back again in the work of visual artists. Hence, elements such as realism, naturalism, and freedom begin and end in visual arts but they are mediated through the moving body of Duncan.

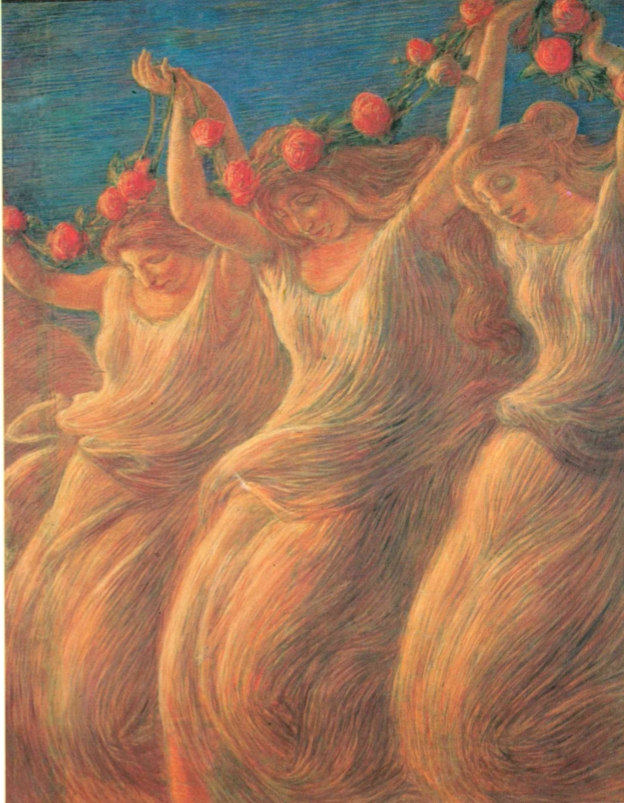

The Dance (or Pastoral) (1908) by Gaetano Previati. Oil painting on canvas.

The exhibition A Passi di Danza — the first of its kind in Italy — offers two distinct lines of narration towards this direction while being divided into ten thematic sections. The first line of narration concerns her biography and work during her years in Italy (1902-1906 and 1912-1915) — including the collaborative projects that she activated with the pioneer theatre maker Edward Gordon Craig and the actress Eleonora Duse — along with her imprint at the Free dance movement. Besides the paintings and sculptures depicting Duncan (notably Eugene Carriere’s Portrait de Isadora Duncan, 1901; Antoine Bourdelle’s Projet de monument a Falcon d’après Isadora Duncan, 1911) the exhibited material is supported by program notes from her performances in Italy, excerpts from her writings where great reflections can be found, photos, Gordon Graig’s sketches, even some of her tunics, and a rare audio-visual material that aims to create connections with her contemporaries in dance. It all gives further insight into her life and the tragedies that she faced while making clear the evolution of her dance from the Apollonian to the Dionysian aesthetic.

Dancer with a circle (1913) by Ercole Drei. Bronze statue.

The second line of narration concerns the works of art that have been dedicated to her and the dancers who followed her example. Among the more notorious works of art found in the exhibition is Duncan as Gioia (1914) in Plinio Nomellini ‘s painting — which became the cover of the catalog and the promotional material of the exhibition–, Libero Andreotti’s Pleureuse (1911) and the portraits made by Romano Romanelli (1913). Walking between works of art made by independent artists, pre-Raphaelites, and symbolists, what becomes evident is the freedom of movement expression and emotion that inspired these visual artists to capture in time and space. In her dancing, Duncan was emphasizing the process of movement, not the finished poses as it used to be in Classical Ballet, and that seems to have been the point of interest for many artists featured in the exhibition: to capture the expressive body in the process of moving. In these works, the body is not depicted as an austere unmovable object but rather Duncan and the other female bodies are often celebrated in expressive forms in which the solar plexus is elevated towards the sky or in poses which manifest the moving power of dance (as seen in Giuseppe Cominetti’s Lussuria, 1910; Gaetano Previati’s The Dance, 1908; Ercole Drei’s Danzatrice con cerchio, 1913).

The exhibition concludes with a part on futurists, who were opposed to Duncan and her followers. Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, the founder of the Futurist movement, accuses her, in the Manifesto of Futurism, of a lack of technique, excessive expressionism, disparate nostalgia of the past and even of being childish. This counter-position is a valuable section that offers a round view of the controversial figure of Duncan.

Drawing on the influence of Duncan upon the Italian avant-garde artists, the exhibition shares an affinity with a current tendency to explore the relationship between Dance and the Visual Arts. This is a trend that keeps on growing under the financial support of the European Commission (e.g. the project Dancing Museums), the initiatives of well-established exhibition spaces (Danser Sa Vie , 2011-2012 at the Centre Pompidou in Paris; Move: Choreographing You ,2010-11 at the Hayward Gallery in London), retrospective exhibitions (notably Sasha Waltz. Installations, Objects, Performances , 2013 at ZKM Karlsruhe; Yvonne Rainer: Dance Works , 2014 at Raven Row in London) and several academic publications. Although differences in terms of aims and objectives prevail among these projects, they either seek to historically contextualize the beginnings of the cross-over between Dance and the Visual Arts or examine and expand the potential contribution from this cross-over. Dance and Museum Studies currently conduct inter-disciplinary research on areas such as curation and space-making as choreography, alternative modes of archiving dance and they generally aim to offer new embodied experiences to the audience of the museums and galleries. Keeping in mind this context, how does the setting of the exhibition A Passi di Danza reflect or even acknowledge this turn in Curation Studies, influenced among others by the Relational Aesthetics? How does it emphasize the experience of the Spectator? Curation is aligned with a sort of choreography where spatial arrangements and economies of time — beyond the chronological order as time, sequence and categorization — become its fundamental characteristics. How is spectatorship in A Passi di Danza affected by curation seen as a form of choreography?

A Passi di Danza follows a rather traditional curatorial approach inside an atmosphere structured in a hierarchical order that imposes the institutional conduct of a visually-oriented experience in which the works of art are mainly observed as objects. Considering the architecture of Villa Bardini, the limitations of any sort of experimental curatorial approach becomes clear. However, a series of choreographic events devised for the Room Annigoni and the external spaces of the Villa Bardini and commissioned to the Centro Nazionale di Produzione | Virgilio Sieni helped to overcome this rather conventional approach in exposing dance-related material. Although limited to a few appointments, the project Atleta Donna is a contemporary response to the concept of freedom and it is consisted of three parts: the dance performance Canto al Silenzio, a workshop to get familiar with the basic principles of dance and Vita_Ballo Isadora, a performance by young dance performers inspired by the artistic and ideological principles eminent in Duncan’s work. Sieni’s project enlivens the atmosphere of the Villa Bardini and helps to place the living body to the center of producing historical knowledge.

Despite this partially traditional curatorial approach, the exhibition gives the chance to study the freely moving body and its transformation into a static object, full of dynamism, expression, and movement. Also, it gives an insight into the exchanges of visual arts and dance and contributes to acknowledging the importance of Duncan, not only in the field of Dance but in the social and artistic realms of her contemporaries as well. It is a hymn to the female body that strives to be liberated from the social constraints and be prepared to claim its social and political rights.

General Info:

The exhibition was curated by art historians Maria Flora Giubilei and Carlo Sisi in collaboration with art historian Rossella Campana, archivist Eleonora Barbara Nomellini and dance scholar Patrizia Veroli. It was produced by the Fondazione CR Firenze and the Fondazione Parchi Monumentali Bardini e Peyron under the support of the Municipality of Florence. Featuring artists include: Auguste Rodin, Franz von Stuck, Umberto Boccioni, Fortunato Depero, Felice Casorati, Gio Ponti, Antoine Bourdelle, Eugène Carrière, Ferdinand Hodler, Edward Gordon Craig, Leonardo Bistolfi, Edoardo Rubino, Adolfo De Carolis, Gaetano Previati, Giulio Aristide Sartorio, Plinio Nomellini, Romano Romanelli, Ercole Drei, Domenico Baccarini, Galileo Chini, Dario Viterbo, Hendrik Christian Andersen, Francesco Messina, Francesco Nonni, Antonio Maraini, Amleto Cataldi, Libero Andreotti, Giuseppe Cominetti, Thayaht, Gino Severini, Mario Sironi, Amedeo Bocchi, Antonietta Raphaël, Pericle Fazzini, Massimo Campigli, Adolfo Wildt.

A Passi di Danza ran in Villa Bardini in Florence from the 13th of April until the 22nd of September. Since the 19th of October, it has been transferred to MART (Museo di Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto) where it will be open to the public until the 1st of March 2020.

For visiting the exhibition, a good knowledge of the Italian language is highly recommended. It is addressed to an Italian-speaking audience as all the supporting texts — including the catalog — are written in Italian.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Ariadne Mikou.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.