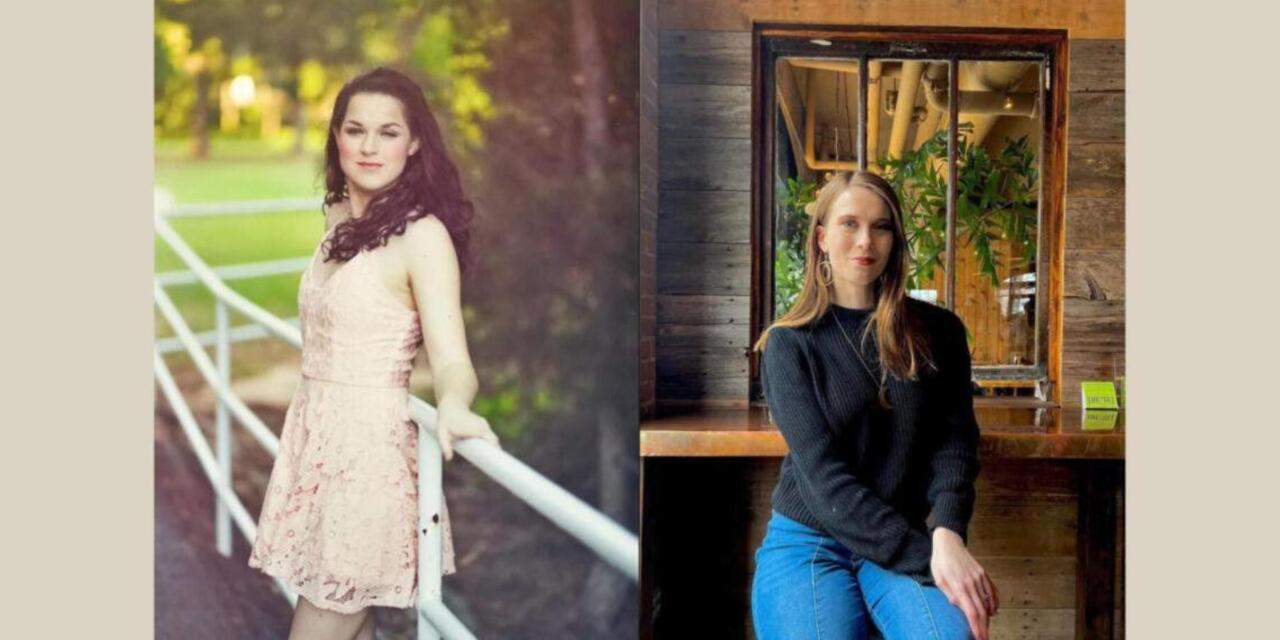

Regan Hicks is one of my dearest friends and closest collaborators. We’ve worked on a number of projects together over the past few years, each time beneficial, each time an utter delight. This summer, I co-directed the first workshop of her newest piece, an immersive Celtic folk musical about the first immigrants to pass through Ellis Island, entitled Liberty. Serving as her dramaturg and director has been the greatest joy. I consider her one of the brightest new talents emerging in modern theatre, and I could not be more thrilled to introduce you all to her today.

Join us, in Part One of this two-part series, as we discuss the creative and development process, the amplitude of research that goes into historical theatre, and telling the stories of forgotten women!

Rhiannon Ling (Dramaturg/Director): So, as we jump into this little chat session for The Theatre Times…Miss Regan, do you want to introduce yourself?

Regan Hicks (Playwright/Composer): I would love to! My name is Regan Hicks. I am an actor-singer-writer-musician based in New York City, and I wrote a little musical called Liberty: A Celtic Musical. I wrote the book and music and lyrics, and I recently produced—(Rhiannon snaps in praise)—yes! I produced recently the first ever official workshop of it, which was very exciting! With my beautiful friends Rhiannon Ling and Shelbe Overby.

RL: Yes! So, for folks at The Theatre Times who don’t me yet: hi, I’m Rhiannon Ling. I’m a writer, dramaturg, actor, and, now, director—

RH: Yes!

RL: (laughs) –in Brooklyn, New York. I do a lot of different things, but for Liberty, I have been the ongoing dramaturg and recently co-directed this workshop with Shelbe Overby. So let’s get into it. The first thing I want to talk about with you, Regan, is the inspiration behind this musical. I remember being in a forum at CAP21 Conservatory, and you were talking about, “Hey, I have this kind of, like, little idea for a musical. It could be kind of fun.” And I said, “Yeah! I’d love to see that. Let me know when you write it, and I’d love to be involved!”

RH: Yeah, that was, like, five years ago now, or four years ago. I remember we were in the studio after we had a class meeting, and I was nervous to talk to you because I knew that you were this brilliant writer yourself, and I’ve always written growing up, songs and plays or TV shows, just to myself. But I’d never produced any of my works before, and so I was nervous to mention it to anyone! It was kind of like, that was my hobby, my secret hobby. (both laugh) But then I remember, yeah, I had this idea, and I was like, I think this is a great idea, and I just wanna tell someone about it, and I felt like you were the perfect person to, so it was just a divine blessing that I reached out to you.

RL: It was a little serendipitous for us both, yeah. Where did you first encounter Annie Moore [Liberty’s protagonist and first immigrant through Ellis Island]? I don’t think I’ve ever asked you that. When was the first time you met her?

RH: That’s a good question. First of all, I’ve always loved Celtic music. I’ve always loved folk music, and, growing up, I was always listening to folk music, and ‘70s folk music and my mom would play some Celtic music. She grew up listening to a couple of the Irish trad songs because my grandparents loved listening to them and had some of those albums. And so my mom grew up listening to some of it, and, therefore, I knew a lot of songs. Then I developed this love of it, too, once I started getting more interested in my ancestry; once I found out that I have quite a bit of Irish ancestry on my Dad’s side, I kind of became obsessed with it. And I just was, yeah, adding things to my Spotify soundtrack, and I was craving more folk music that had Celtic background involved, and then I came across Celtic Woman, which I became obsessed with.

RL: As one should!

RH: As one should! Everyone should love Celtic Woman. They covered a song called “Isle of Hope, Isle of Tears,” which is a beautiful ballad based on Annie Moore and her travel from County Cork to America and being the first on Ellis Island, though it doesn’t talk a lot about her life, it just mentions her in a few of the stanzas. And the song is just so beautiful and inspiring. And I was listening to it on an airplane…(she laughs) I remember distinctly, I was listening to it on an airplane, and I got very emotional about it, and I just wanted to know more about who she was. ‘Cause I thought, this sounds like a great story, and a great idea for a musical, especially, because Celtic music is very story-focused, and especially because I’m someone who enjoys Celtic music, and I write heavily in the style of folk, I thought, I should explore this, and see if someone already has a musical about her, or if there’s anything about her. And then I did some Googling—a lot of Googling (both laugh)—and I found that, to my knowledge, no one else had written anything about her, besides some websites that had some information. And there really wasn’t a lot of information about her! They don’t even know exactly what age she was, or a lot about her family. They just knew that she was from County Cork, that she was approximately seventeen, that she had her two little brothers, and that she was going to be with her parents in New York. So I thought, y’know what? I’ll fill in the gaps, I’ll make my own show, and tell my own story! Y’know, put myself in her own mindset, and write from what I feel like she would have been experiencing at that time. To revive her and to tell her story, but also to tell the story of immigration, because at the time, too, there was the immigration ban going on, and I felt very inspired to tell a story from an immigrant’s perspective to remind us all that we’re all immigrants—most of us, besides the Indigenous populations—we’re all from other places, and therefore it’s silly to discriminate against people for being immigrants, wanting to have a better life, when that’s exactly what our ancestors did. So I felt very inspired by what was going on in the world at the time, politically, and also the history of our country, ‘cause I’m a history nerd—

RL: Me, too. (laughs)

RH: (laughs) Yeah, I’m a nerd! And with that connection with Celtic music, it just felt perfect for me, especially, as an artist. It just felt very poignant at the time, and for me.

Regan Hicks, Nikki Rinaudo-Concessi, and Ellie McKee Johnson in the workshop of “Liberty.” PC: Rhiannon Ling

RL: Yeah. You said so much interesting there that I’d love to talk about, but—(Regan laughs) There are three major points of your inspiration there that I think are really powerful throughlines through Liberty, and they have been since the first time I got to read it [in 2020], in its very nascent stages. I still remember when you sent me the email with all the original demos, by the way, and I got them stuck in my head!

RH: (groans) Oh my god, on Soundcloud. They were so bad!

RL: They were not bad; they were good! But a couple of things I think are really interesting are…obviously, you heard about Annie through Celtic music, through the song. You mentioned that Celtic music is very story-driven. But I feel like a lot of cultures that have been oppressed, or cultures that have ties to the ancient world, let’s say—because America is such a young country—oftentimes they tell things through an oral tradition, or it’s through music. I mean, that’s all the Celts, that’s most cultures in Africa, that’s Eastern Europe, that’s everywhere that isn’t the “developed Western world.” So it makes perfect sense that you would write a musical about it, because how else would Annie tell her story, y’know?

RH: Exactly.

RL: And in addition—I mean, you know this, but for the Theatre Times folks who don’t—I am so passionate about telling forgotten women’s stories—

RH: Oh, yes!

RL: So I immediately jumped onto, “I don’t know who Annie Moore is! She seems like an important person. Why do we not know about her?” And the beautiful and the sad thing about covering these women’s stories is that you really do have to fill in the gaps, because there’s just not much record. And unless the family kept good records—which, frankly, there’s a good chance they didn’t—we’re not gonna know much about them. I’m running into the same issue with some work I’m doing now, trying to figure out, “Who were these people?” So it’s a beautiful thing as a writer, but it’s a really sad thing as a person.

RH: Exactly. And also, that’s prevalent, too, with ancestry and just history in general, a lot of records are just forgotten about or burned up in fires, and so a lot of history is just forgotten, which is sad because we can learn a lot about ourselves, and that can teach us a lot of great messages, and so it’s sad that, as a society, we kind of just brush past it and forget about it.

RL: Yeah, it’s cyclical. I think it would really help us to empathize with each other if we could understand, that this is where we came from. I heard someone once say that if you respect yourself, you respect other people, and I don’t think that’s inherently true always, but it certainly helps.

RH: Very true! (both chuckle)

RL: And the immigration ban. Interesting that you bring it up, because I remember talking about this right at the very beginning. It’s still applicable now; it’s certainly not in the forefront of the political sphere at the moment, but, honestly, I think some of the messages that you’re telling would even fit into something like Black Lives Matter, would even fit into talking about Indigenous folks in America. I’m kind of curious, about how applicable and apropos that is: how did you go from “I want to tell a story about Annie” to “I want to tell a story about all these immigrants who came together, and their issues that they had”?

RH: I think I had to start…I mean, this was years ago now, I think we agreed that it was about two years ago that I really started writing it. I got the idea, but then we were in the middle of college, so, I didn’t have a lot of time. And then once the pandemic hit, I was like, okay, it’s now or never—I’ve got time on my hands, ‘cause I’m not going outside of my house—so I really sat down and started writing it. I kind of had to start small and get larger with the scope. I started with Annie, researching as much as I could about her, and trying to figure out what her arc would be, and where I wanted her to grow to, and what her story was. And then once I knew I needed to add more characters for her to interact with, and I knew I wanted more stories, and I knew I wanted to talk about immigration and how America has treated immigrants very poorly—always has, and continues to, which is very sad—I knew I wanted to talk about that, and really deconstruct those issues and hold up a mirror to our modern society by saying, look, this has always been happening. And I knew I wanted my characters to overcome that, and to show that they can have sympathy and empathy for each other, and that we can reverse the discrimination and the prejudice that they’ve been bred to feel towards each other. So I knew I wanted to do that. But I think that, really, I had to start with Annie, and once I started adding in the [Kelly] brothers [Liberty’s romantic interests] and their relationship with their grandpa, and I had that idea that, oh, they’re gonna be rich, and that’s gonna cause conflict because the class divide. And then, I remember, I came to you, and I said, “I’m wanting to have a Romeo and Juliet situation with one of the brothers,” because I also wanted to talk about the racial divide. I wanted to have a class divide and a racial divide. And I wanted to make her German at first, because I also have German ancestry, and I was like, I kinda want to do an homage to that. But then the way it worked out, because I also know some Italian, I was like, “I want her to be German or Italian,” and you were like, “Well, historically”—because you’re brilliant—”it would make more sense to make her Italian.” It just worked out perfectly, because, once the Italians and the Irish came to America, they had this big rivalry. It was perfect that I could touch on the racial prejudices through that. So I think that once I started to work my way out, it all just came together to tell the story, and also to have multiple messages come across—hopefully—that the audience can learn from.

RL: For sure. I really appreciate the fact that you don’t shy away from the ugliness that would have even happened on the boat, as well.

RH: Yes.

RL: I mean, oftentimes immigration stories are told through the lens of the film right now, no pun intended. (both laugh) I feel like, for a good while there, there was almost…I’m gonna use the term “romanticized.” Even gangster movies. Those aren’t romanticized in the sense that they’re bloody and gory, but they’re still some version of “this is what the whimsy of it would’ve looked like,” that’s the plotline. And the direction in which you’re heading, I think, balances those. You obviously said “Romeo and Juliet,” so you do still have that concept of, this is a classic MT [musical theatre] move, with our primary and secondary couple…

RH: Yeah. Plot- and structure-wise, I kept it like that, but you’re right.

RL: But you don’t shy away. I mean, you’ve got the “filthy Italians,” you’ve got the “Black Irish,” and all these horrible names that they would call each other, and then Americans would call them. And I think that’s something that too often gets forgotten now. As you said, that treatment happened continuously, we just chose a new group of people every time. So being able to tell that within the realm of a love story—whether it’s a love story for yourself or for another person—that you’ve done, is really refreshing and I think really poignant, and, the more that you build on it, it will get even better.

RH: Another little thing that I want to add, too, is the other subplot I knew I wanted very early on: Maggie and Mary, the [Irish] sisters. I don’t want to give anything away about the ending—! (both laugh) But with them and their plotline, I wanted to talk about all of those who it didn’t work out for, all the immigrants who came to America with these big dreams of gold on the streets, and we’re gonna be successful, and everything’s gonna be fine, and we’ll find cures for our illnesses. But, for a lot of people, it didn’t work out. I knew I wanted to touch on that, and so I wrote those characters in quite early on, and I knew I wanted to use them to spearhead that plot and that message.

RL: And you did it very well! I think something that we probably can say without giving away the end is that it doesn’t end, quote-unquote, “happily.” And I think that’s something that really…I’m gonna use the word “refreshing” again, it’s really refreshing. We don’t get that romanticized version of, “And then the streets were gold, and they had a great life!”

RH: I remember, too, that I gave the script to—you were the first person I gave it to because I trust you, and I love you and your work and your writing, and you’re a genius, so I trusted you and I gave it to you. But then I also gave it to some teachers and mentors and friends, and colleagues, who I wanted to get their opinions. And I had a few people say that they wished that it had a happy ending, “maybe rethink that,” like a Disney movie or something. And I really felt in my gut that, no, it needs to end not exactly happily. I want it to be inspiring and uplifting, and I want especially Annie, as the main character, to find hope in the end, but I knew that I didn’t want it to end happily, ‘cause a lot of people didn’t have a happy ending. And so I’m happy that you—and I had a handful of other people, too—say that they liked it. I’m very happy that it works. (both laugh)

RL: It’s grounded is what it is, because not everyone gets a happy ending. They get fine endings, usually, but I think it’s so powerful to show that things did not work out, and it really provides some complexity to your characters. I mean, worth noting, as well, that, like you just said, it doesn’t end sadly, per se.

RH: It’s not sad!

RL: It’s not sad! But we do get that glimpse of “What are their struggles gonna be now?” Which is really powerful for the end of a show, I think. Since you started talking about your earlier subplots, I would love to talk through, especially for our audience, the process of developing this over the past two years, which I know is a daunting discussion question.

RH: I’ll try to keep it short.

RL: Bullet points!

Regan Hicks and Korina Deming in “Liberty.” PC: Rhiannon Ling

RH: Bullet points! Yeah, so, as I previously stated, I got the idea about four or five years ago, and I came to you, and I said, “Hey, I have an idea that I really want to explore.” And you said, “That sounds cool! Work on it! And come back to me!” And then, two years ago, when the pandemic really hit, I said, “It’s now or never,” and I sat down. And I remember I was stuck at home, doing Zoom school, and on, I think it was during Christmas break, I just cranked it out. Christmas happens in the show, so I was really inspired! (both laugh) And I really just started cranking out the script. And I had pieced together some songs that I had written. I think the songs—not all of them, but some, like “Wild and Free” was the first one I ever wrote, “Sailing Blind” was an early song that I wrote, and “On My Way.” Those popped out of me, and I wrote them down as ideas, and it’s crazy to think that they’re still in the show in some form. They’ve changed quite heavily since then, but those were the first things that I wrote. Then I puzzle-pieced everything together from there. And then, after I had the first draft of the script, I sent it to you, and you gave me a lot of great feedback and edits, and ideas, and you were very influential. I would consider you one of my editors. You helped me so much with fixing little problems or even expanding upon things that you saw potential in. So, I went back and did a bunch of edits, and I also then gave it to Shelbe about a year ago. And then she got involved in the project, and she helped me heavily with the music, ‘cause she’s a songwriter herself. And I also gave it to mentors of mine and did some heavy rounds of edits. And then, I had a Zoom reading, because I knew I needed to hear it out loud. So I got together with you, Shelbe, and a handful of my friends who are singers and musicians, and we made music demos and we got on Zoom last fall, or right before Christmas, and we had a Zoom reading. It went great, and then I went back and did some more edits. I posted about my Zoom reading, and Angelo Fraboni, from the Madison Theatre on Long Island, who’s someone that I’ve worked with before, reached out to me on Facebook and said, “Hey! Why didn’t you send this to me? I’d love to read your script and maybe help you produce a workshop.” So, I sent it to him, and we had some meetings, and I roped Rhiannon and Shelbe into being my directors and choreographer and dramaturg. The Madison Theatre agreed to produce the first-ever staged reading and workshop, and we got a cast together. It felt like forever, but, really, it was such a quick process. In two weeks, we put a show on its feet!

RL: We put a dang thing up! (both laugh)

RH: It was such a whirlwind of a process, but it was so beneficial to see it on its feet for the first time, to see how it stood, and to realize that it does stand as a show, was amazing. I’m so happy that it worked out the way it did.

RL: For sure. One of the best parts about seeing your show on its feet is realizing it does actually work, right? Like, that’s your number one realization that’s helpful to have. Because it’s such a bolster to have the “Okay, I know that this does work, now let’s just make it better” as you’re continuing to develop it.

RH: Exactly.

RL: So I’m glad that you saw that because you have a show!

RH: Thank you!

RL: That was just such a surreal experience, honestly. I mean, it was our first time out of college really producing anything ourselves, which was crazy. The fact that we did it—we had monetary assistance, but pretty much nothing else—

RH: Yeah. We had a million hats on. For being so young, and this was our first time wearing multiple hats, I think…I mean, we did it! I’m very proud that we were able to put on a show by ourselves and that it came out the way it did. I’m very proud of us and very happy that it worked out the way it did. And really, we also just got so lucky with the creative team—I got so lucky with the creative team, y’all are amazing—and we got so lucky with the cast, and the band, and, yeah, just everyone was so passionate about the project and the story and the music, that it really made the process fun and productive and a wonderful experience.

RL: And so willing to just jump in and make mistakes and play around.

RH: And bring things to the table, too! Because they were originating the characters and bringing the music to life for the first time, and the script to life for the first time. So it was amazing to see them just jump into the deep end and make choices and be brave.

RL: And to feel comfortable enough to say, “Hey, this isn’t working for me. Can we try it this way?” Or “What if I did this?” Or “Hey, what about this?” You’re the writer, so you can say your own situation, but sometimes actors don’t do that, or the room that it’s within does not feel safe enough to do that in, so it’s just wonderful that that atmosphere was created, and they felt like they could do that.

RH: Exactly. And speaking as the writer hat, I just feel like we got so lucky with having actors who…first of all, we knew a lot of them, because that’s how they got involved, and so I think that created an air of fun and playfulness, that we trusted them as actors and they trusted us as a creative team, that they could make choices and bring things to the table. Also, the fact that our fearless leaders, you and Shelbe, were so open to having them bring things to the table and create, make changes, and big choices to bring the characters to life. You really set the standard for the room, making it fun, and making it a room to play in. And then me as the writer, too: I am so chill. I am one of those writers and creatives where I want it to be a collaboration. I want my people who are involved in the project to feel free to come to me and say, “I feel like my character would do this,” and I go, “Great! I totally see where you’re coming from. Let’s do it, and see how it works.” Even with music, too, if someone’s making some changes to music—especially folk music, too, it’s so freeing—just make choices, and, as long as you’re telling the story, that’s all I want.

RL: I’ve never understood directors and writers who are so precious about their work that they don’t want to hear anybody else’s thoughts. Art-making is just so intrinsically collaborative. It doesn’t really matter what medium it is. Even if you’re working by yourself, you’re still gonna have an editor, a reader, and an audience. Nothing is by yourself, and trying to play it that way just feels so selfish to me and so counterproductive. So I’m glad Shelbe and I were able to get to that, and I really appreciate you, as a writer, being incredibly open to feedback. I think you’re starting to strike such a good balance between “Yes! Tell me what you think,” and standing steadfast in knowing that that part needs to stay that way.

RH: I definitely agree. It was a big lesson since this was the first time I’ve worked on a project this big that I’ve written. It was such a learning curve, getting so much feedback from so many different people, the musicians, the different creative team members, and our cast, and, even with the talkback too, there was a point where there were a lot of cooks in the kitchen, and I really had to learn, like, okay, what can I take, and say, “Yeah, okay, they’re seeing something that I’m not, and I need to be able to tweak,” and also say, “Okay, this is something that I really want to keep in the script.” And as the writer, I’m the ultimate decision-maker, I guess—I am! I am the ultimate decision-maker! And so, yeah, realizing when there are too many cooks in the kitchen and when I need to decide when my gut tells me to stay or go, versus…and I do, I love getting feedback, because if I’m getting feedback, it means that people are passionate about the story, and see potential and want to make it better. So I really appreciate all the feedback I get.

RL: I am curious, as I never asked you this point blank, what are the things that you learned, either about your script or the development process, through doing this workshop? Perhaps the top three things.

RH: Hm…well, first of all, I would say exactly what I just left the last conversation on. Being able to find a balance, putting on my writer hat and finding that balance of taking all the feedback I can, but also putting my foot down and knowing when to be the final say, when to make a decision and when to—what word do I want for this?

RL: When to be malleable, versus—?

RH: Yeah, having that balance of accepting criticism and accepting feedback, but also knowing in my heart what needs to stay for my story. So that’s one thing. Another thing, too, is wearing the hat of a writer and actor. This was my first time doing that. And I feel like, for having my Lin-Manuel Miranda moment…(both laugh) It’s hard, but I also really enjoyed it. And I think I really enjoyed it and was able to find that balance because I had such a wonderful directing duo. I felt comfortable knowing that both of you know this story as well as me, and all three of us knew exactly what the story needed to be, and we all had a very similar vision, if not the same exact vision, and I feel like that really helped make it easy for me to be able to take off my writing hat, especially towards the end of the process. I was able to take off my writer hat and just keep my actor hat on, and I felt comfortable doing that because I knew that you both saw my vision and that you could take it in your hands to bring it to life. And I think I got very lucky with that, that both of y’all were involved and were so good at your jobs. There are two things for you….

RL: You don’t have to have a third! That’s A-okay.

RH: Then I think those two are pretty solid lessons that I learned, and great experiences.

RL: The dual perspective is so interesting because you have the macro and micro going on at the same time. It’s difficult to switch between those two parts of your brain.

RH: And I will say, too: it was hard to transition from writer to actor. Like, once I knew that I trusted both of you—of course, I’ve always trusted you with the work, but once I convinced my brain that and was able to take off the writer’s hat, I found it difficult to get all of the other characters’ voices out of my head, and just focus on Annie’s voice, and making choices for Annie, and just being Annie for that process.

RL: I can imagine! Speaking as a writer, yeah, you have twenty different voices going on in your head all at once because you have to track all those storylines. So to suddenly react in real-time…you really have to feel that out.

RH: Exactly. But once I knew what that transition was and that I just had to focus on Annie’s role, then it was a lot of fun, and it was just…a learning curve, but, yeah, a lot of fun.

The full cast of Regan Hicks’s “Liberty: A Celtic Musical.” PC: Rhiannon Ling

Keep an eye out for Part Two, where Regan and I discuss crafting art as a young, female-identifying creative, the necessary changes in the industry, and even what theatre can gain from video games!

This is part 1 of the bipartite interview. To read part 2, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Rhiannon Ling.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.