This is part 2 of the bipartite interview. To read part 1, click here.

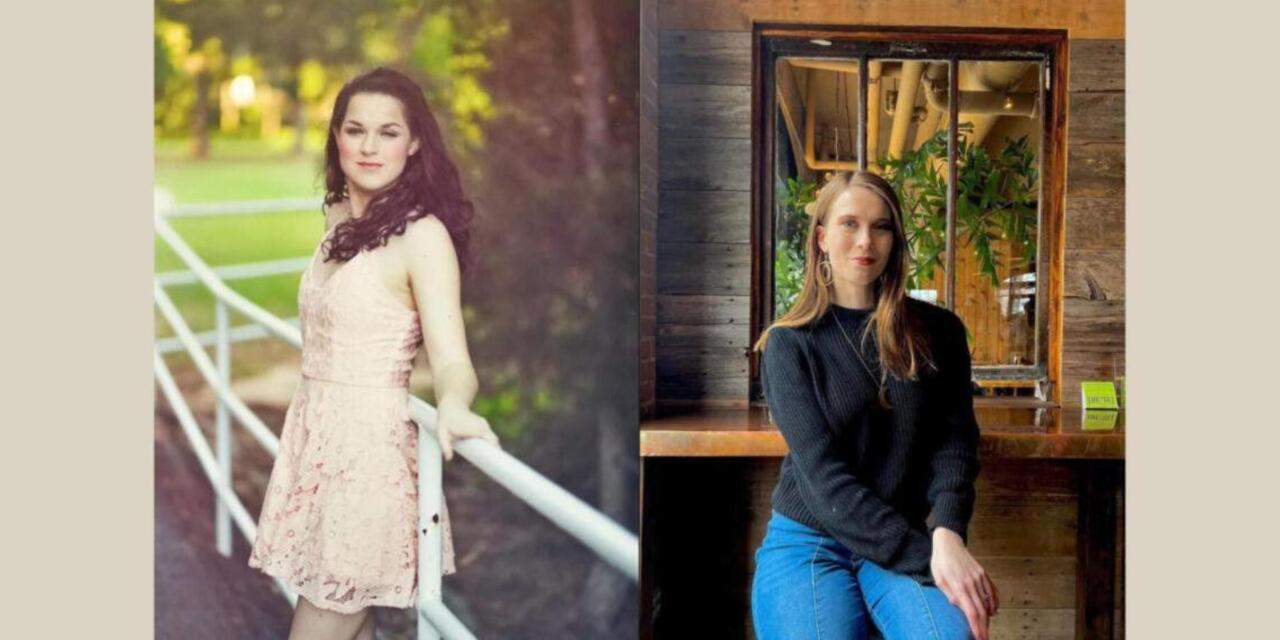

Welcome back to the second and final installment in my conversation with my dear friend and collaborator, Regan Hicks, a luminous emerging theatre artist. If you missed the first part, I highly recommend you check it out. If you have, welcome, and enjoy our chat about producing works as young, female-identifying artists, the needed changes in the industry, and even what theatre can gain from video games!

Rhiannon Ling (Dramaturg/Director): A good time. (both laugh) So, we’ve chatted about the development process, the surrealism of producing it and learning from that, so I would love to hear—maybe I’ll just give you a really general prompt here—what’s it like being a young, female-identifying creative in the industry today? What has been your experience thus far?

Regan Hicks (Playwright/Composer): It’s funny, I was just thinking about this the other day. I am very fortunate that I grew up with such a supportive family and such a supportive group of friends and teachers, and such a supportive community, that it never felt like I had any obstacles in my way. I realize that I’m very fortunate in that way; I feel bad that there are young creatives out there, particularly female-identifying—and also because I’m white, I realize I have that privilege, as well, and I grew up in a community that was very supportive of the arts—I was very lucky that I never had any obstacles. I mean, I do, but it felt like I didn’t, so I always approached the arts and the entertainment industry as, “Oh, I can do that! I can do anything! I just need to go out there and do it!” Then, as I got older, and I went to college—and I feel like in college, especially, then I started to realize, “Oh, wait a minute. There’s a lot of prejudice against female writers.” There are not a lot of female writers! There’s not a lot of representation! And it shows in a lot of shows that I was watching and seeing. I was like, eugh. I really wish that there was more of that representation behind the table, and particularly young voices, too, because a lot of us younger writers are dying to get our stories out there, and dying to get into the room and let our voices be heard and our opinions and the messages that we want to send out there. But I’ve noticed as I’ve gotten older and I’ve realized that there are hurdles, that it’s hard to get new stories, younger stories, out there, because older, mostly male-identifying, mostly white men, are the ones in the way, blocking our stories from getting there. And most of them are producing the shows, as well, so I’m finding it more and more difficult. However, I’m happy that I still have that little bit of childlike innocence in the sense that I’m like, “I’m just gonna do it, anyway. I’m just gonna go out there.” I even talked to you about this! I was like, “If no one will produce it, I’m gonna raise money.” I was like, “How expensive is it to buy a Broadway house and put on my show?”

RL: (laughing) I remember this discussion!

RH: So I’m very innocent in that I—I’m so nerdy, but I’m gonna bring this up. I went down a rabbit hole of watching Marlon Brando interviews and Orson Welles interviews and old-timey interviews because I’m that nerd. And Orson Welles even said, when he made Citizen Kane, which was revolutionary—and he was young at the time, he was only 25, he didn’t know how to make movies—and that’s the reason that he was successful and so innovative because he had no idea what he was doing. And he even said that! He said, “No one wanted to produce it, and so I found people who said, ‘I wanna produce your work, because you are young and you don’t know what you’re doing, and that’s beautiful.’” And so, I’m finding that, especially after hearing his interview where he talked about that, even though there are those hurdles where no one’s gonna wanna produce my work because I’m a woman, or because I’m young, or because whatever if I keep that child innocence that “I’m just gonna do it anyway,” that that will hopefully be beneficial. Or, because of social media nowadays, there are so many other ways to get work out there. I’m hoping that will be helpful, for me and also for other young artists out there and young writers. Hopefully, we can get our work out there through social media, self-producing, and other ways than just needing to go to the big uppity producers who might block us from their theatre. That’s a long answer. Sorry.

RL: No, that’s a good answer. It’s such an interesting balance to strike, right? Because I feel like, especially when you are not the cisgender, heterosexual, white, wealthy male that’s been running the show for so long, you kind of inherently have to keep that childlike innocence or the fight of, “Well, I’m gonna do it, anyway.” You have to be stubborn or naïve. But at the same time, when one is, in whatever intersectional way it is, in the group that’s not getting their work out there, you also can’t afford to be either of those things. You have to have that innocence in that sense, while still realizing that, “I have to get over these hurdles. This is what I have in front of me. How can I be smart enough to get around those?”

RH: Exactly. I like that you mentioned stubborn because you really do have to be, I’m finding, especially as I’ve been having more and more conversations with people who don’t know the industry very well. Y’know, family friends who say, “Oh, how’s that writing thing going?” Or “How’s that acting thing going? Are you gonna be on Broadway? When are you gonna be on Broadway?” Or “When are you gonna get this produced?” And I keep having to try to educate them, saying, “Well, it’s not that simple. There’s a lot more to it.” And also, you can’t really box yourself in, saying, “This is my one goal. I’m just gonna do this.” You really need to be emboldened and approach things as being a stubborn and very forward artist, in the sense of putting yourself out there, putting your work out there. But in a nice way! And also—going back to the collaboration thing—sticking together as young artists is also gonna help us. For example, you and me, being young, female-identifying artists. Both of us helping each other to produce our own work, and helping our work to get out there, is also what’s going to be very helpful, because, one of these days, those people who are in charge are no longer going to be in charge. They’re going to be dead, or retiring, or whatever. We’re going to be taking up the throne, so to speak, and so sticking together and really sticking up for each other’s work, as well as being stubborn in putting our work out there, but making sure that everyone’s voices are heard, is also going to be beneficial for us as a group of young, up-and-coming artists.

RL: Yeah. That’s it. That’s a great point to bring up, this whole concept of being strong in unification and strong in amplification. Because who is going to make sure the work is heard if it’s not us? Advocating for not only our friends but for people who have not had their voices heard in a very, very long time. Whether in terms of being the literal writer, the literal creator, of the work, or having that representation be onstage, on film, in video games, whatever it may be. I mean, as you mentioned…I grew up in a very supportive family for the arts; I grew up in a community that had arts in it, but it was certainly not an arts-supportive community. And because of that, most of the shows that I saw when I was younger were gonna be mega-commercialized ones. And until you get to the point where you can consciously start looking at this, it’s so hard to realize that there is more out there than Christine Daae. There’s more out there than Nabulungi in the Book of Mormon. Whether it exists—and it does, and it’s just not getting produced—or it exists in someone’s brain and just hasn’t been put out there yet, for a variety of reasons…and, granted, I gotta acknowledge that this is a really difficult thing to talk about, because there are so many layers to it—

RH: There are so many layers. And another thing I’m gonna add, too, is: I was just working in All Shook Up, and LaVon, who played my mom—LaVon Fisher-Wilson—she mentioned that someone asked her recently, “What’s your dream role?” And she said, “My dream role hasn’t been written yet.” And I love that she said that, because it’s true, there’s not—y’know, she being this beautiful, strong, black, belting woman, she said, “There are roles out there for me, but they’re not roles that I really want to play, that I envision myself playing.” She wants to be the lead role that has a romantic plotline, as well as a strong, independent plotline, and that hasn’t been written yet. And that really got me thinking, too, that, yeah, there’s a lot of roles out there that, because they’ve traditionally been written by men, stereotype women. Like, I’m gonna be typecast as the naïve young ingenue girl, and she’s gonna be cast as—for example, in All Shook Up—she’s the woman who runs the bar, and that’s just the type of it. And I really hope that those, with the wave of younger artists who are bringing new stories to the table that are from our perspectives of female-identifying, gender neutral, queer, strong black artists, really being able to push their stories to the forefront, I’m hoping that, like she said, her story will be written. And the roles that we want to be playing, and the roles we want to see come to life onstage, will be written, with us being able to produce our own stories.

Regan Hicks and Django Jacobson-Fein in “Liberty.” PC: Rhiannon Ling

RL: You’re right in the sense that we get pigeonholed so often. Women get pigeonholed so often; queer folks get pigeonholed so often; Black, Indigenous, people of color get pigeonholed so often. I mean, you and I, you just acknowledged this, we have privilege in the fact that we are white, but we still get…like, you’re the naïve young ingenue; I, as an actor, am either gonna be the sexy one or the mom, there’s no in-between. (both laugh) And it’s so frustrating to do that. And also in the sense of being, as both of us are, multihyphenated in the creative world, so often people ask you, “So, what do you wanna do? Do you want to do this, this, or this? Do you wanna be onstage or off? Do you wanna—?” Well, why can’t you do all of it? It makes you a stronger artist! (both laugh as Regan gesticulates wildly)

RH: I just had this conversation this morning! And I got—I’m getting worked up—I got on my soapbox about this! This morning, I was talking with my dad and a family friend, and the family friend was like, “Yeah, so when are you gonna be on Broadway, performing on Broadway, as an actress?” And I was like, “Here’s the thing!” And then I got on my soapbox, and I was talking about how, I remember, back in college and even in high school, I expressed, as my naïve young self did, that I wanna be a writer, and I wanna be a singer/songwriter/folk singer, and I wanna be an actor, doing, y’know, Broadway, regional theatre, and TV/film. I wanna do it all. And I remember I had people saying, “Oh, you have pick between TV/film or the stage. Oh, you have to pick between writing, and directing, and acting, or being a singer/songwriter. You have to pick one of the roads.” And I very stubbornly said, “No.” And here I am, trying to pursue multiple things, and now I’m very happy that I’m finding that…like you, like Shelbe, and like all of my friends, I think our generation is very much of that mindset, too, where we are not going to listen to the people who told us we can’t do it. And I’m happy that we’re not, and that we didn’t, because I’m finding that there’s so many more opportunities, and that we’re all building new opportunities for us, as an industry, and as individual artists. And I’m very happy about that. I thought I was the only one back then, and now I’m finding after graduating, this community of younger artists—or maybe it’s just the community that I’m finding because I’m finding like-minded people—we all have so many different hobbies, and we want our careers to go in so many different directions, that it’s beneficial to wear multiple hats.

RL: Yeah, to have those multiple avenues. Two things I want to say about that to get us back on track, because both of us kind of went off on a little—(both laugh)

RH: A little tangent, a little soapbox! (both laugh)

RL: Two things I want to say about that. The first one, where you said you got on a soapbox with a friend: something I find minorly exhaustive, because I’m just experiencing this as a woman and a woman within the LGBTQ community, I’m not experiencing this as a woman of color or a nonbinary person or anything like that: it is exhausting to have to explain things to people, all of the time. And this comes in a variety of ways, so I’ll stick to the female-identifying perspective, which we can both speak to. As a writer selling yourself to a mostly male room, or having to explain why a female character is acting the way that she is, because they don’t believe it. As a dramaturg, I’ve had to explain to well-intentioned directors why they can’t just throw people into intimate scenes without doing anything with them. (Regan cringes) Again, well-intentioned! Just not raised to that. Or things like, as an actor, having to say to a writer, or a director, or a dramaturg, “This is not working as a female person, and here’s why. This is not believable. This is not realistic.” And it being very blatantly clear that either they didn’t think about this beforehand, they didn’t talk to anyone, or, in the far more unfortunate circumstance, they don’t care. That is so frustrating, and I’m sure you relate.

RH: Yeah. I mean, you pretty much hit the nail on the head about all of those points. It’s frustrating feeling the need to educate everyone, and especially a group of people who, as you said, don’t care about learning, or don’t care about changing. And I feel like it’s particularly hard because the people who are in charge, y’know, older generations who are a little bit more stubborn—going back to that word—in their mindset, or the way that they know how to do things and how to work in the industry—because the industry is evolving and changing, as it should—I think, yeah, it’s frustrating to run into those people who, like you said, aren’t willing to listen. It’s important to get our voices heard, but it can be frustrating.

RL: Because you shouldn’t have to, right? You should introduce people to new things; you shouldn’t have to explain or justify your existence. Yeah. Great. I’m gonna have us move on from that. (both laugh) We kind of hit on this, but I’d love to hear you, as someone who just had a workshop, talk a little about it: Liberty, of course, is a smaller musical on the scale of spectacle value. We eventually want to have it in-the-round or immersive, even; it has a small band that is onstage the whole time; it has just a Celtic trad band; it’s supposed to feel like you’re in a pub. Most musicals now are adaptations or highly spectacled. I’d love to hear from you, as someone who wrote a folk musical that is smaller in scale, how has it been crafting that and starting this commercial development process in an age that is so heavily focused on commercialization and monetization?

RH: That is a great question, and I’m gonna try to answer it, because it’s a big question—

RL: It’s a lot. I know it’s a lot.

Olivia DeFilippo and Timothy Thomas in “Liberty.” PC: Rhiannon Ling

RH: You and I have talked extensively about this, about how commercialized everything is. Especially as we get older—like I was talking about the naivete of me being younger and thinking “I can do anything,” and then now as I get older, and am trying to produce this as a young artist, I’m finding that everything is so commercialized, and the producers are really going after money, and what is going to make money. Which is sad to me. And I think…yeah, every show nowadays that I see coming out is a movie musical musical movie. (both laugh) And me personally, I just—I know that what they’re thinking is, “Oh, this’ll make money,” because people will know this title, and they’re gonna wanna see that—but me personally, I want to see new stories, I want to see an original piece, I want to experience something completely new, and from a perspective that we’ve never seen before, and I want to learn something new. As well as be entertained. But I want to learn something and see something completely new. And I feel like all of the writers who are making something new, the best new works coming out right now, are video games. As an avid gamer, I love it, but it also makes me sad. I don’t know if it’s because the video game industry is so new, maybe that’s why there are so many new stories and so many new writers being able to produce original stories through that medium, but I feel like, in Hollywood and the theatre world especially, they’re just making remakes or they’re rebooting, or they’re movie musicals. And it makes it difficult, I think, for new works, especially by younger and new, emerging artists, to make it “to the top,” because the producers are going after what is going to make money, which is stories that have been told that they know will be successful. Did I even answer the question?

RL: You did! And what’s so frustrating, as well, to agree with you real quick, is that people will watch whatever is on Broadway, just because it’s on Broadway. That’s the stamp of approval, even though it’s not always the most innovative. So if you get the new stuff onto Broadway, people are eventually gonna watch it, inevitably. Just a thought. Anyway.

RH: I agree wholeheartedly. Just to add, very briefly: Broadway is for people who aren’t in the industry, who don’t realize that there are so many new works out there, not even in New York. In every state, there are so many great theatres and productions happening that, unfortunately, I think the general public, who are not in any way involved in the entertainment industry, and especially not the live theatre industry, they don’t realize that, and they just see Broadway as the end all, be all. They see Broadway as where the best is. They’ll see anything that’s there, because, you’re right, it is the stamp of approval. I think it’s a little bit easier for those of us who are working in the entertainment industry to realize that there are so many up-and-coming works to pay attention to, and that Broadway is great, but it isn’t necessarily the end all, be all. It’s a great platform, but there are so many other great platforms out there.

RL: Absolutely. And what, in your opinion, as you’re heading forward with selling this piece, and continuing to edit and workshop and get productions—and there will be future productions—what do you think is going to be your biggest obstacle?

RH: I think my biggest obstacle is going to be the size of the cast…

RL: It could even be the specific instruments you need.

Django Jacobson-Fein and Regan Hicks in the workshop of “Liberty.” PC: Rhiannon Ling

RH: You’re right, you’re right, thank you for bringing that up. The specific instruments. Because it is highly stylized. But I think that’s also the draw of it, and so I think that could have pros and cons to it. Because I need and want a bodhrán player, and a concertina player, a fiddle player, things that are very specific to the style, I think there’s a charm to that that potential producers would think, “Okay, we can overcome that obstacle.” Or they might be scared, and not want to produce. But I also think the size of the cast is a challenge, based on, coming back to it again, money. Because right now, producers are looking and going after things that they know are going to make money. Looking at, particularly in times of COVID, when it’s a challenge to have such a big cast, and it’s expensive to have a big cast, I think, and especially for a little musical like mine that doesn’t have a big name to it yet…I’ve even bumped into this before. I’ve submitted to some theatres, and I’ve had them very nicely reach out to me and say, “Unfortunately, at this time, we cannot produce it.” And I really sat on it, and thought, well, y’know, that’s probably a big reason, too. Right now, a lot of theatres are producing smaller plays, with small casts, without bands, things that are easier to produce for them monetarily. And that’s totally understandable, but makes it hard for me to produce this, because that’s a big challenge.

RL: Thanks, COVID.

RH: Thanks, COVID. Exactly.

RL: Regardless, you’ve got a great show. I’m sure someone will get to it.

RH: Thank you! I hope so. I’d love for someone to see the potential and help me take it to the next level and bring it to its fullest form.

RL: So to wrap us up, what would you like to plug, my dear friend? Your Instagram, your TikTok, what would you like to give to the good people?

RH: Oh my gosh, I get to plug myself! I’m on Instagram and Tiktok, at @_regan_hicks_. You can follow me on there to see what I’m up to, my other projects that I have going on, and other folk music and stuff. I hope to see y’all out there!

A massive, massive thank you to Regan Hicks for her time, her thoughts, and her artistry. Visit her on Instagram and TikTok to find out more about what she does and the future of Liberty! As for me, you can find me on Instagram at @rhiannon_ling_. We’ll see you there!

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Rhiannon Ling.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.