There is a balm in Gilead, and Gilead is not here. It’s the promise of that biblical medicine, of suffering and pain given way to the sweet release of liberation, that moves Pharus Young (Jeremy Pope), the character at the heart of Tarell Alvin McCraney’s glorious Broadway offering, Choir Boy, just as it has others who’ve wandered in some desert and sung to make the wounded whole.

For Pharus, that desert Sinai is an elite Christian prep school for young black men, his exodus there delivered on account of that peculiar “swish,” that feminine step and swagger in his walk. Here, “trust and obey” is the motto, the gospel.

The enduring questions asked by W.E.B. Du Bois — How does it feel to be a problem? Why did God make me an outcast and a stranger in my own house? — stir the air of the Oscar-winning playwright’s (Moonlight) exuberant Broadway debut. But the double-consciousness that troubles his lionhearted protagonist, that measuring of one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt, is not one of being black and American, but being black and queer, Christian and gay.

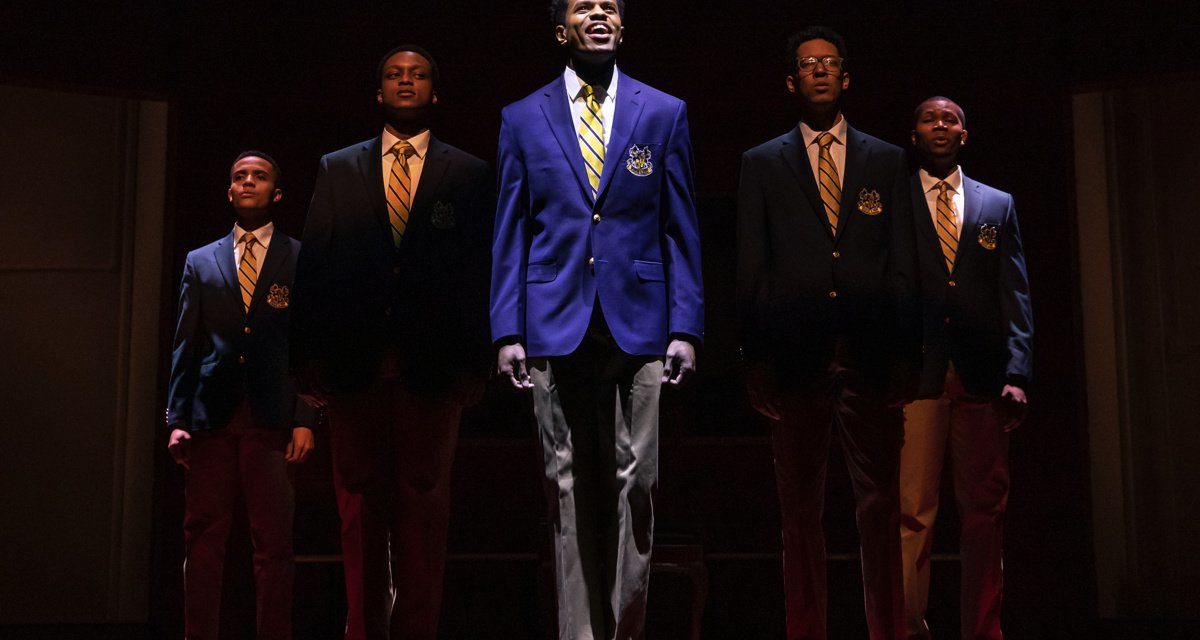

Choir Boy, first presented at Manhattan Theatre Company in 2013, is not simply a musical play — it is itself a spiritual whose song, sung triumphantly by the bountiful talent of its leading star, Jeremy Pope, rises from its stage with the same faith and fearlessness of a prayer sung only for the stars.

The melodies of the slave spiritual, of “Motherless Child” or “Wade in the Water,” and the anthems of the Civil Rights song, of “Keep Your Eyes on the Prize,” are sole bearers of salvation for Pharus, the lead singer of the Charles R. Drew Prep School choir. They are a map, a guide and an appeal to godly courage as Pharus is lashed with homophobia, gay-bashed by members of the choir he leads. The devil has a tireless mind, he’s told; wade in the Jordan, and let God trouble the water.

But Pharus does not break. Instead, he embodies the “fiercely sunny strife,” as Du Bois would have called it, of being black and gay and Christian, peculiar in the way of never having been anything else.

Battered by the violent homophobia of his peers, abandoned by a school administration that averts its eyes to his bullying, Pharus doesn’t shrink into silent hatred, disdain, and defeat. Never does he allow his audience to witness the lifting of that vast veil he necessarily wears, to see him yield in resigned reconciliation of his faith and identity.

Pharus is fearlessly himself, a unique creation, and if he is troubled it is because he knows the lessons needed to free both himself and those who torment him are twice-told in the songs they sing.

In Pharus’ singularity must also be Jeremy Pope’s brilliance. Sometimes like fire, other times like rushing water, Pope, who originated the role in 2013, moves across the Friedman’s stage, his shining tenor soaring above it, with an intensity and urgency that alone drives this production. Perhaps if he moves fast enough — if he dishes out Pharus’s bottomless well of perfectly timed comebacks at an impressive speed — no one can stop the character he portrays with such protection, no one can listen long enough to tear down the strength Pharus tries so hard to build. And that’s first-rate acting.

Few other choir boys are given the level of depth McCraney imbues in Pharus, with the lone exception of the homophobic and volatile Bobby (J. Quinton Johnson), nephew to Headmaster Morrow (Chuck Cooper) and leader of Pharus’s persecution, whose scholarship and “legacy status” at the school raises questions of class privilege in the black community and church. Jason Michael Webb and Camille A. Brown, whose musical direction and choreography place the rock on which McCraney’s church is built, shine as brightly as Pope.

A central question McCraney has sowed in Choir Boy is that of the slave spiritual’s function. It’s one that enthralls Pharus to the play’s end. Yes, slave songs were spiritual guides for their singers, but were they also literal ones? Did “Wade in the Water” carry hidden messages for crossing the Mississippi, as folklore has it, or were Jordan’s healing waters stirred simply by an unwavering faith, the song simply a “spiritual”? For Pharus, whose burden in shouldering the weight of living queer and black and faithfully dedicated to God is nearly beyond the measure of his strength, the answer seems like an urgent one.

Yet, as Choir Boy concludes and his protagonist graduates, McCraney offers no solution. Instead, Pharus, mouthing those words “trust and obey” — in whom now more clear than ever — smiles into the light, left to wonder, just as we are, whether the freed will find freedom in the promised land.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Michael Appler.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.