Playwrights Horizons’ production of I Was Most Alive With You by Craig Lucas was otherworldly in aesthetic and story. Ash is a reformed addict and is enjoying his life as a writer and father to his son, Knox, who is Deaf and a recovering addict. His carefully constructed world falls apart one Thanksgiving evening when Knox and his lover, Farhad, get into a car crash, which leads to Knox’s relapse and a seemingly unending string of unfortunate events. Ash tries to make sense of these events by working with his writing partner, Astrid, to create a TV show based on them.

Upon the moment of entering the theater, it is tempting to crawl up on the stage and be enveloped within its atmosphere and the tale it tells. The home-y set provided the stage with depth and numerous places for actors and props to hide, making each glance one takes at a particular part of the stage a feast for the eyes. Two moveable pieces of furniture allowed for small transformations to indicate different living spaces, which were effortlessly made by the cast. The balcony erected above the living space served as a space for the ASL cast and the theoretical outside world of the writing studio/house/apartment.

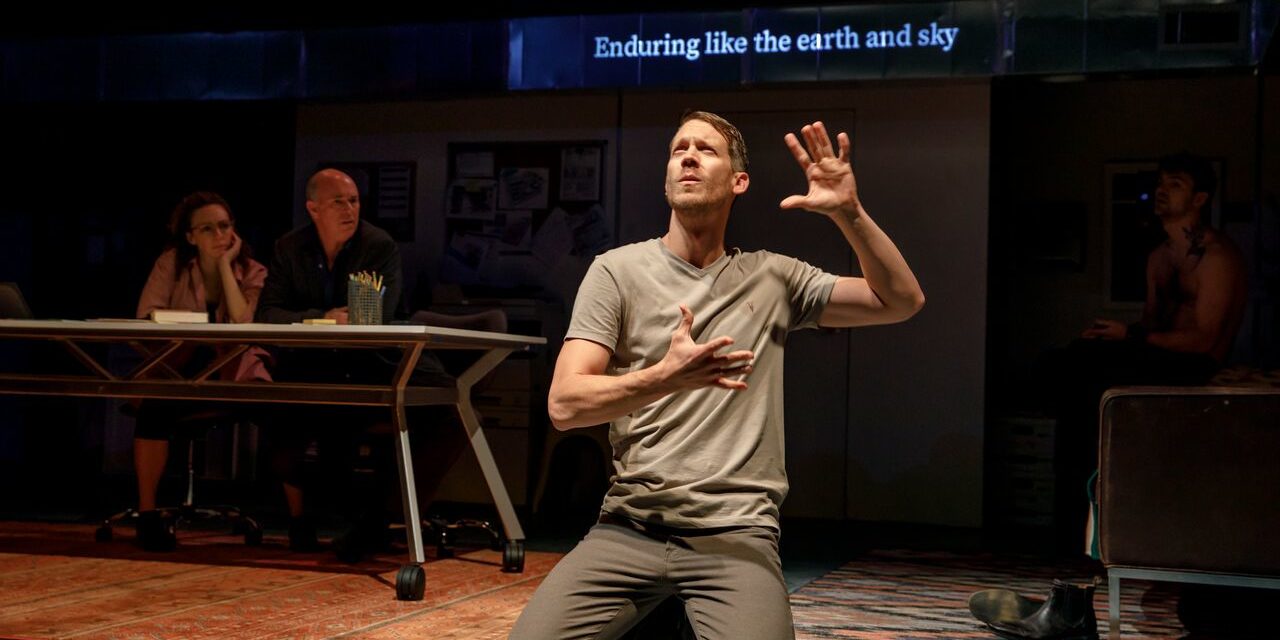

Marianna Bassham (Astrid) & Michael Gaston (Ash) in foreground; and Beth Applebaum (Shadow Astrid) & Seth Gore (Shadow Ash) above |Photo Credits Joan Marcus

The utilization of a second cast of ASL actors who mimicked the speaking cast’s movements both positively served the D/deaf community and added complexity and meaning to the play. The bookshelf backdrop connected them to the speaking cast through the set and the ASL cast added a layer of communication to a play peppered with inconsistent and sometimes unwanted interaction. At times, the use of ASL added a beautiful final component to the signing and speaking of the main cast, like when Knox prays or when the whole family has a group conversation. The ASL was used in a way that served the needs of the D/deaf community, paid tribute to their unique form of communication, and didn’t patronize–all of which are rare when it comes to representing disability in the theatre. Ultimately, the use of ASL–both as a tool for D/deaf audience members and as part of the play–looked natural, and that was the aspect that mattered the most.

The structure of the play was at times, linear, and at other times, not, which mostly worked for the story, but was also the cause of some issues and oversights. The plot itself was sporadic, but it served the play’s purpose. However, the lack of exposition made the first act confusing, especially in regard to familial relationships and the unfolding of events. The heightened pace of the first half only added to this confusion, as it was difficult to process the action and figure out each character’s place in the story. Most other aspects of typical narrative structure are sprinkled in here and there–including multiple climaxes that serve to relay the story–but ultimately, the nonlinear structure accurately mirrored the constant shifts from Ash’s memories to the present lives of the characters.

The hectic speed and complication of the beginning half of the play was offset by the second act, which occurred after Knox’s accident. While it was just as intriguing as the first act, the characters really begin to open up, and the audience gets a deeper look into how they work and how the accident has affected the entire family.

The ensemble | Photo Credits Joan Marcus

Early on, Pleasant, Knox’s mother, decides to leave her son and husband, as she feels like she is a burden and has lost herself. The fact that she is one of the weaker constructed characters made her departure seem like it happened on purpose to make the story flow smoother and finesse it, which was a good call on Lucas’s end. While the removal of a character can sometimes be seen as negative, in this case, it enhanced the other character’s relationships and helped the audience to understand what problem to focus on–Knox’s relapse and downward spiral.

The marketing for I Was Most Alive With You indicated that Ash was the main character, but the play itself said otherwise. Ash took on a narrator role, while much of the story revolved around Knox, which created more empathy for him and caused Ash to fade into the background. He does have his own story, but it gets pushed away, and he becomes more of a character than a human being. While he is focusing on his son, it seems like he loses sight of his own self, and even though there are hints from other characters that it’s possible Ash will also relapse, he never visibly struggles with that. The problem with this sort of erasure is that the audiences loses a different perspective on the problem at hand and the character becomes one note.

Craig Lucas has written a show that is thought-provoking and heartbreaking with (mostly) dynamic characters who clearly undergo many transformations. He also employed the use of ASL and ASL actors and used them in a way that paid tribute to the D/deaf community. In his own words, Lucas states that Deafness “opens up new perspectives of seeing and feeling that are less accessible to hearing humans,” and I Was Most Alive With You certainly gave New York audiences a new, positive perspective of the D/deaf community.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Madison Parrotta.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.