Scenic designer Sean Fanning recently designed a beautiful and provocative set for Jack Thorne’s 2015 play The Solid Life of Sugar Water, produced by Deaf West Theatre. This was Sean’s first production with the company whose mission is as follows:

Deaf West Theatre, Inc., was founded in 1991 to directly improve and enrich the cultural lives of the 1.2 million Deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals who live in the Los Angeles area. DWT provides exposure and access to professional theatre, filling a void for Deaf artists and audiences.

Serving the cultural, educational, social and employment needs of its constituents, DWT is an institution for the discovery and exploration of artists’ identities and stature as artists. Through the medium of Sign Language Theatre, a legacy of Deaf culture is created, shared, and preserved.

Although Sean identifies as a Deaf/HOH (hard-of-hearing) designer, I know him to be highly functioning in the hearing world, so my interest was piqued when he posted the following on social media:

A shout-out to Deaf West Theatre for being the company I needed in my life right now.

For a long time, the theatre tech period has been a challenging stage in my process, one that took everyday obstacles and heightened them further. Tech, for me, has always been (1) turn off the lights, (2) stumble around in the dark, and (3) struggle to communicate as my 8-foot rule (I can’t understand you past that radius) becomes significantly shortened when faces are obscured. I’ve dealt with a variety of different collaborators in that setting—some are incredibly understanding, and some don’t have the time to be bothered. Seeing a hearing creative team and a Deaf cast learn to work together during a tech process has been eye-opening. I have the gift of an ASL (American Sign Language) upbringing and being on the threshold between two worlds (Deaf and hearing) has allowed me to see and interact with both sides. It has been fascinating and ground leveling for me.

Inclusivity is a buzzword that gets thrown around a lot these days. Real talk: it’s time to have a discussion about what inclusivity actually means, not just for audiences, but in our workplaces.

I wrote to Sean and asked him if he’d like a platform to discuss his experience further and he agreed to sit with me for an interview.

Michael Schweikardt: Tell me about the play.

Sean Fanning: The Solid Life of Sugar Water is a play about a couple, Alice and Phil, who are struggling to connect after a miscarriage. It is about what happens when the plan you had for your life ends in a tragedy that you couldn’t see coming. How do you recover from that? How can you save your relationship and rediscover intimacy when your whole world feels as if it’s been turned on end?

As written, the character of Alice (Sandra Mae Frank) is a Deaf woman, and the character of Phil (Tad Cooley) is a hearing man. Early on, it was decided that both characters would be played by Deaf/HOH actors using ASL. To be clear, the character of Phil is still a hearing character, he is simply being played by an HOH actor. Since The Solid Life of Sugar Water is a memory play, the conceit is that Phil has since learned to sign—to the Deaf audience the quality of Phil’s signing made it clear that he was not a native signer. So, the play could remain accessible to both a Deaf and hearing audience, two hearing voice actors were double-cast in the roles of Alice and Phil (Natalie Camunas and Nick Apostolina, respectively), and they performed simultaneously on the periphery.

Much of the rather graphic play is told through interior monologues. The use of ASL brought a colorful dimension to the script by providing a visually playful way to look at some frank, sexual descriptions. It had a disarming effect on the audience that brought them closer to the characters.

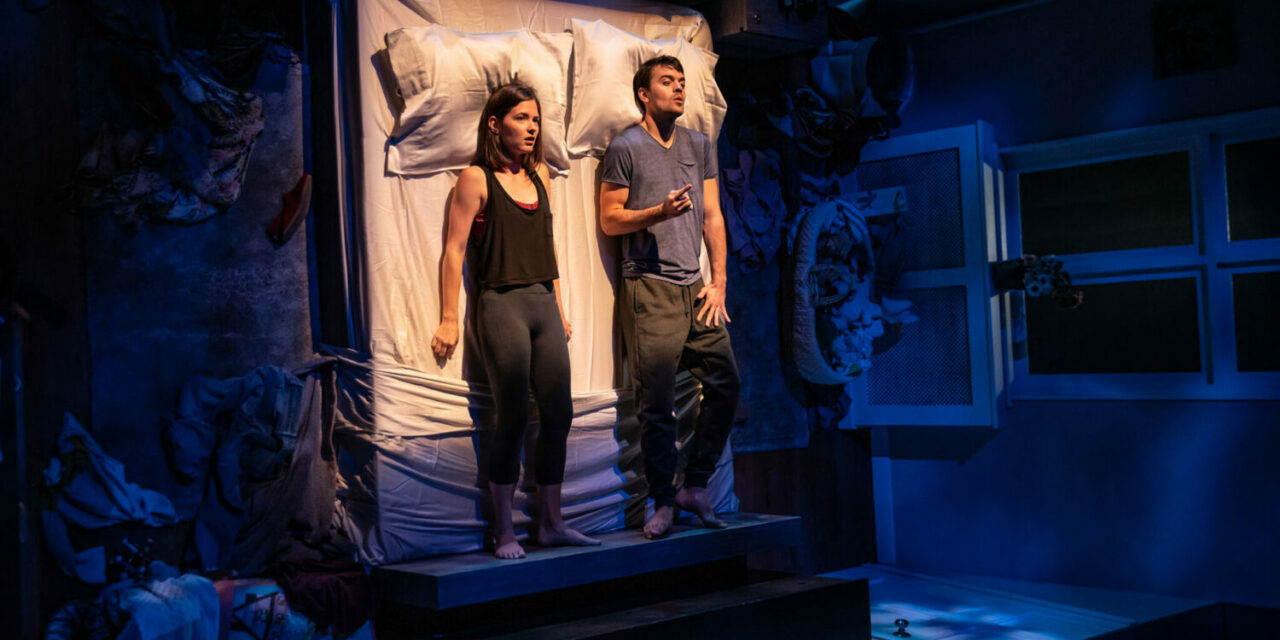

The Solid Life of Sugar Water. Photo by Brandon Simmoneau.

For more about The Solid Life of Sugar Water:

MS: Can you tell me a little about your design?

SF: For a great deal of the play, Alice and Phil are in bed together. They aren’t actually engaging in sex acts, but they’re talking about them to the audience. Putting the bed in a horizontal position would make this really hard to watch. The original UK production used the premise of a “vertical bed” and I thought that was a brilliant solution. That version of the set was simply a wall, a bed, a floor. I chose to use that idea of the vertical bed, but I surrounded it with all the details of the rest of the room—there are prenatal vitamins and medications on a nightstand, there are toys and stuffed animals (gifts from a baby shower) strewn about, there is a Moses basket on the floor ready for a baby that didn’t live. The set is built in a calculated forced perspective that gives the illusions that we are looking down on Alice and Phil’s bedroom from the point of view of someone on the ceiling (the set construction was by Red Colegrove at Grove Scenic). While this created a voyeuristic and unsettling quality that fit the tone of the play, it also created a major technical challenge. All of the dressing—in fact, every element in the room—had to defy gravity. A heap of clothes on the floor is simply that but put it on the wall and it is suddenly sculpture.

The Solid Life of Sugar Water. Photo by Brandon Simmoneau.

For a Page to Stage Video:

MS: Why did you need Deaf West Theatre in your life?

SF: I identify as a Deaf/HOH designer. I was born with a bilateral, sensorineural hearing loss that registers (at 90-110 DB) as severe-to-profoundly Deaf. I’ve used hearing aids since I was two months of age and mainstreamed throughout the school. Although I grew up with ASL, I function more like a hearing person. To understand people, I read lips and piece together bits of what I can hear them say. I fool a lot of people because I speak very clearly (15 years of speech therapy is no joke), and my detective work keeps the illusion going. For a great deal of my life, I’ve felt like I needed to make a choice between the Deaf and hearing worlds. Choosing the former meant ditching the hearing aids and communicating only in ASL. Choosing the latter meant speechreading and speaking without falling back on ASL or an interpreter. I chose the latter, but it has always been a challenge. For many years I harbored the feeling that, because I function the way I do, the Deaf community would not see me as one of them. Working at Deaf West proved that wrong. Through meeting the actors and working with the community surrounding the company, I learned that there is a whole spectrum to being Deaf. Some wear hearing aids while others don’t, some use voice and some turn off the voice, some rely on interpreters more than others. being Deaf is not just one thing. There was something so heartening about being a part of that.

MS: What is tech like for you?

SF: Tech is good for me when people are patient and consistent in communication style, and when there are avenues of accessibility.

A “bad tech” for me is one that is disorganized and has people mumbling in the dark or shouting across the theater. Sometimes I wish I could put people in my shoes, just for a moment, so they could feel what it’s like for me to be isolated in that situation, always concerned that someone might be calling my name and getting frustrated that I’m not responding immediately.

Tech at Deaf West felt like a great equalizer. Since we had a hearing director and Deaf cast members, every day of rehearsal included an ASL interpreter as a go-between. We integrated the use of lights into the tech process because signing in the dark is hard to see. I could sign as much as I wanted during tech rehearsals because it was silent and non-disruptive. I was able to sign with the actors and, at the same time, I could go over to the director or costume designer and have a spoken conversation. Finally, I found myself in love with an aspect of myself that once made me uncomfortable—being between two worlds. Being me suddenly felt like this great superpower!

Scenic Designer Sean Fanning.

As I’ve grown older and more confident, I’ve begun to embrace my identity as a Deaf person. I’ve shifted from “trying to fit in and passing for hearing” to just being me. What does this mean? Well, I’m not going to “fake it” for anyone any longer. I’ve grown tired of pretending to understand everyone. I’ve grown tired of smiling and trying to keep those around me comfortable with my disability. Nowadays, more and more, I work to control situations so that I will have equal access. This means I’ll position myself in the room so I can hear you, I will tell you to repeat yourself.

Simply stated, I’m figuring out what it means to be a Deaf theatre artist who functions not like the other artists who are hearing, nor like the other artists who are Deaf, but like me.

MS: What does inclusivity mean to you? What do we, as an industry, need to do to make it real?

SF: Inclusivity is about giving equal access to people or groups who are marginalized.

Making inclusivity real requires a commitment to diversity. When theatres hire homogeneous groups of playwrights, directors, and designers, they form creative teams with implicit bias. It’s up to us as theatre artists to put pressure on our institutions to disrupt these patterns of bias. If we create more diversity, greater inclusivity will follow.

Sean Fanning is a freelance Scenic Designer based in Southern California. Some of his recent design credits include: Mother of the Maid at Marin Theatre Company, Native Gardens at Center REPertory Company, Nina Simone: Four Women at Alabama Shakespeare Festival, Bad Hombres, Good Wives and A Doll’s House Part 2 at San Diego Repertory, Full Gallop at The Old Globe, Pride and Prejudice and On the Twentieth Century at Cygnet Theatre Company (Craig Noel Award for Outstanding Scenic Design). In 2016, Sean was the recipient of the first-ever Craig Noel Award for Designer of the Year. He holds an MFA from San Diego State University and is a proud member of Local USA 829. https://seanfanningdesign.com/

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Michael Schweikardt.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.