Eliza Winstanley, Carte de visite, circa 1860. TCS 19, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

In this series, we look at under-acknowledged women through the ages.

In December 1882, Eliza O’Flaherty died of “diabetes and exhaustion” at her lodgings in Sydney. Aged 64, Eliza lived in a brick cottage behind a dye-works, where she had been employed as a manager for two years. Her demise might seem unremarkable: a widowed, childless woman of the 19th century who had been worn out by work. But O’Flaherty was actually Eliza Winstanley, the first woman to play Richard III in an Australian theatre, and an early star of the colonial stage.

Winstanley was born in Wigan, Lancashire in 1818. With her parents William and Elizabeth and her five younger brothers and sisters, she emigrated to Sydney in 1833. Family stories recall that the Winstanleys went to the Liverpool port intending to emigrate to America but finding no ships bound for America at the docks, they boarded one for Sydney instead.

On arrival in Sydney, the family rented a cottage in Kent Street and soon after William found employment as a scenic artist at Sydney’s first licensed theatre, Barnett Levey’s Theatre Royal in George Street.

In 1834, Eliza, then 16, and her sister Anne, then 9, made their acting debut at this theatre. Eliza performed the role of Clari in The Maid Of Milan, a forgotten musical play known for its sentimental song, Home Sweet Home. She received positive reviews, with The Australian’s critic praising, “the rich intonation of her voice, and the expression of unfeigned grief which her countenance occasionally assumed.”

Surviving hissing from the mob

Early in her career, Winstanley endured the organized attacks of rowdy sections of the audience. The Cabbage Tree mob, named after their distinctive hats made from the leaves of the cabbage tree palm, were fans of the young actress Mathilda Jones, who, unlike the Winstanley sisters, was Australian born. The mob would hiss like geese whenever Eliza and Anne appeared on stage. But over the next 12 years, Eliza refined her craft, becoming one of the most confident, reliable performers on the Sydney stage.

Winstanley’s interest in physical transformation reached its zenith when she was advertised to play the title role in Shakespeare’s Richard III at Sydney’s Australian Olympic Theatre. This was a tent theatre she and her husband, Henry O’Flaherty, briefly managed in 1842. Many reviews describe Winstanley’s physical animation and emotional connection to her roles. She often enacted characters that demanded dynamic vocal and physical transformation, such as hags, maniacs, and villains, which she played, as one critic put it, “with all the powers of tragic acting.”

Shakespeare’s villainous Duke of Gloucester was widely regarded as the ultimate test of an actor’s skill. The character had been played a number of times in Sydney by men, with varying success. Winstanley’s decision to play Richard III indicates she was prepared to take on male theatrical rivals and unafraid of provocative programming.

“Unsexly and indelicate”

Theatre historian Yvonne Shafer suggests that 19th-century actresses played male roles because of “natural inclination, a wish to display ability, and novelty,” and also to “take the lead and compete with men in a very direct way.”

One 19th century critic was appalled by Winstanley’s decision. Although he chose not to attend her performance, he opined, “that the interests of any company of performers would be advanced, by such an exhibition, appears to us to be a most preposterous notion…such an attempt is unsexly and indelicate.”

Unfortunately, a review of Winstanley’s portrayal of Richard III has not yet been discovered. This lack of reviews could indicate that the production was boycotted by the Sydney critics.

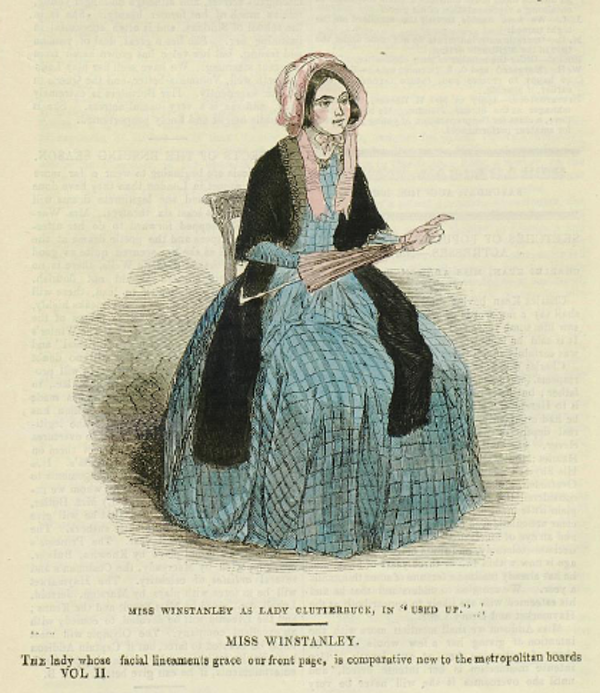

This portrait of Winstanley appeared in the Theatrical Times almost 12 months after she arrived in London as an unknown performer who had trained on the Sydney stage. Courtesy of Senate House Library, London.

In 1846, Winstanley and her husband left Sydney for London. For the next 20 years, she carved out a career under her maiden name and had consistent acting engagements in New York, Philadelphia, and London.

Her days of cross-dressing and physical transformation were now over, and her repertoire consisted mainly of attractive widows, cheerful landladies, and stock theatrical characters known as “heavy ladies.”

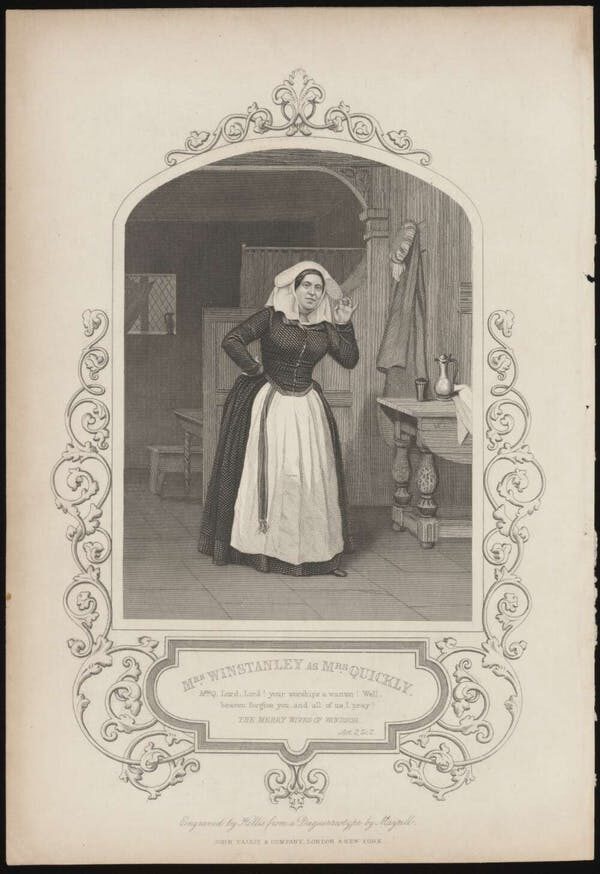

Mrs. Winstanley as Mrs. Quickly [picture] / engraved by Hollis from a daguerreotype by Mayall, c. 1850.Pictures Collection, National Library of Australia

After the death of her husband, Winstanley had to rely on her own resources. She cemented her professional success as a member of Charles and Ellen Kean’s company at London’s Princess Theatre and performed many times in the Kean’s command performances for Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle.

In an 1853 letter to Charles Kean, Winstanley accepts his offer to play Queen Elinor in the Keans’ production of Shakespeare’s King John.

The short note reveals Winstanley’s anxiety about her widening figure, her literary sense of humor and delight in wordplay. “With pleasure, I secede to your request. Though in attempting the part of Queen Elinor I certainly shall fail to represent A leaner Queen.”

Reinvention as a writer

Although she maintained her acting career until the mid-1860s, Winstanley reinvented herself for a second successful career. Her first novel Shifting Scenes In Theatrical Life was published in 1859, and this marked the beginning of her professional life as “Mrs. Winstanley” a writer and editor for popular “penny weekly” magazines.

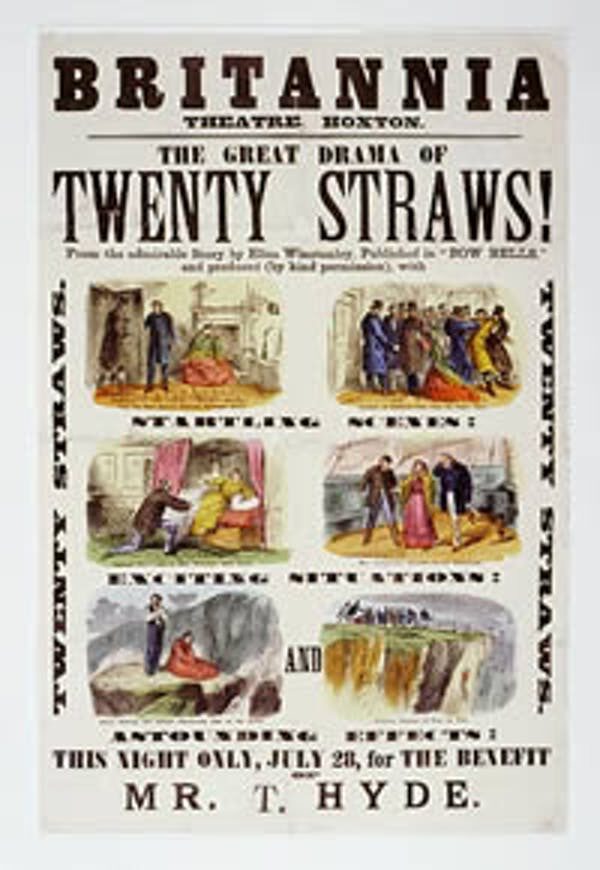

Many of her novels are set in the world of the theatre, and reveal her insider’s knowledge of the acting craft. Some of her novels, including the 1864 convict story Twenty Straws, were adapted and performed at London theatres in the 1860s and 70s.

Playbill advertising a performance of Twenty Straws, adapted from Winstanley’s novel and produced at the Britannia Theatre in Hoxton. Museum of London, c. 1863-1874.

In 1880, Winstanley returned to Sydney, perhaps to be near her brother Robert and his family. As Mrs. O’Flaherty, she found employment as manager of Eldridge’s Dyeworks.

Sydney had transformed from the rough, colonial town she had known three decades earlier. Did any of the older customers of the dye-works remember her as a skilled performer of tragedy and melodrama in the early days of the city’s first theatres?

Eliza O Flaherty’s headstone at Sydney’s Waverley Cemetery. Author provided.

Living as a widow for most of her life, without the material support of a husband, Winstanley adapted to her circumstances. As an actress, she saw employment opportunities dwindle as she aged, and so remade herself as an editor and writer.

As her health declined, she again put her shoulder to the wheel at the dye works.

Winstanley’s three careers are proof of her indefatigable inventiveness in her professional life, and an ability to endure. As a leading artist on Australia’s earliest stages and our first female Richard III, Winstanley deserves a prominent place in our theatrical histories.![]()

This article appeared in The Conversation on May 1, 2019, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Jane Woollard.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.