When Chenura Trust a Zimbabwean media company announced that they were working on a theatrical performance titled Haywire which was going to be centered around mental health issues, initial thoughts were dismissive. I was reluctant to the idea of witnessing another performance on such an important matter that would follow the usual storyline of troubled souls that eventually find solace from their ills without providing details on the characters’ innermost conflicts. However, the premiere night for Haywire at Jason Mphepho Little Theatre in Zimbabwe’s capital city of Harare, progressed in the opposite direction of my expectations.

The story of Haywire traces the journey of a character called Morris who is struggling to navigate through the complexities of life. In the process, he drowns in depression as colleagues and relatives walk away from him. With a heavy mental burden, Morris must gather strength to swim against the strong current of rejection, loneliness, and despair in a fast-paced world. The physical theatre production which was directed and conceptualized by Everson Ndlovu does not only scratch the surface, it sinks deeper in its attempt to project mental health challenges by allowing the audience to experience the internal psychological strife of the character. Watching Haywire for me was like reliving a bad dream, from the perpetual fall that is far from its end to the unpredictable scenes where one is haunted by personal demons with no repose in sight, all interwoven to illustrate the depths to which one can sink when clouded with this mental state.

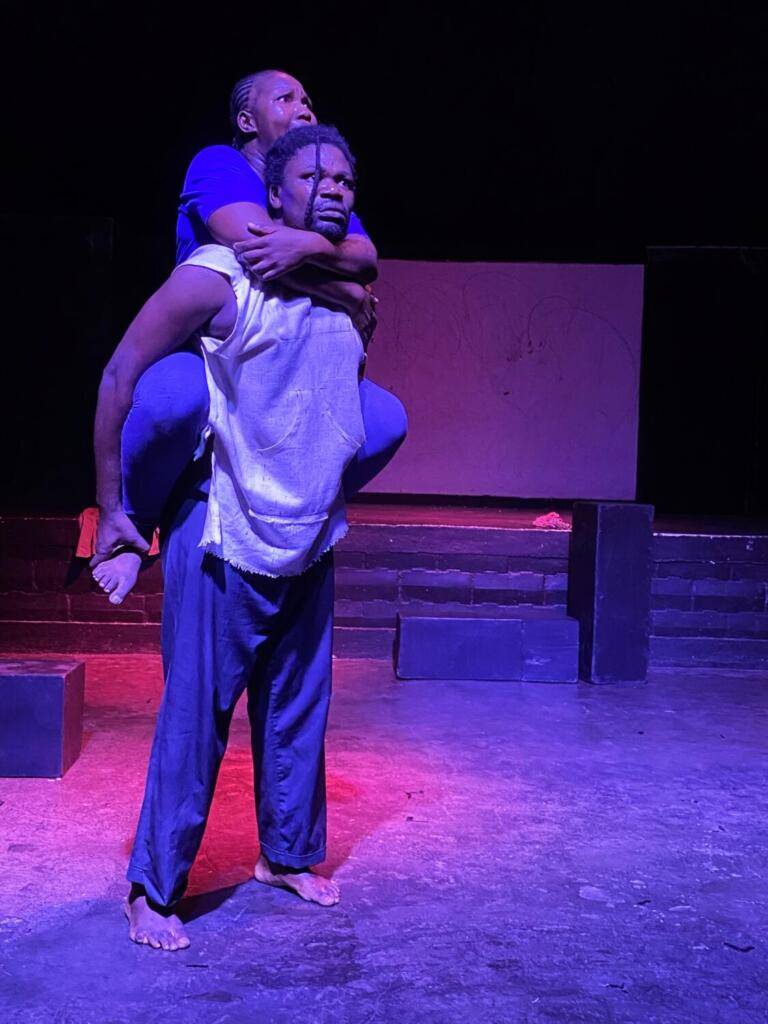

Tafadzwa Bob Mutumbi and Lisa Gutu in Haywire, directed by Everson Ndlovu, at the Jason Mphepho Little Theatre, Harare, Zimbabwe. Photo provided by the author.

It also has to be noted that the production has an intelligent shuffle of characters, the two actors Tafadzwa Bob Mutumbi and Lisa Gutu besides playing other multiple roles, they also take turns to play Morris, the troubled character, in different scenes. At first, it’s seemingly confusing but as the story builds up, one is able to realize that this is a deliberate approach. In the same way, the two actors play the same role of a character sunk in depression, a symbolic message is also being communicated. Morris does not have a single face, with the shifting of circumstances, anyone can potentially be a Morris who is susceptible to the tides of mental health challenges. This view was echoed in the post-performance interview by a fellow Zimbabwean film and theatre practitioner Michael Kudakwashe who said, “We all go through the same thing no matter how we try to hide it, how we try to cloak it, in what we call normalcy. So this play was a relief to see that other people understand what happens when you go through mental health problems.”

Tafadzwa Bob Mutumbi and Lisa Gutu in Haywire, directed by Everson Ndlovu, at the Jason Mphepho Little Theatre, Harare, Zimbabwe. Photo provided by the author.

Outside the gloomy accounts contained in the theatrical performance that range from internal battles with childhood trauma, societal rejection, and the resulting contemplation of suicide, Haywire has a silver lining of hope it projects. The main character Morris finally frees himself from internal shackles that have long compromised his search for peace and happiness. In the final scene, he whispers to himself the words of consolation, “Stop living in the past and accept reasonable changes.” It has to be noted that while theatre might not be the ultimate solution in addressing mental health issues. Its contribution is essential in breaking the ice around such complex themes.

Haywire is presented in a minimalistic fashion which makes it easily adaptable for different performance spaces. Besides the black rectangular blocks which can be easily altered to recreate different scenes, there is very little to write in terms of props used in the production. Much of Haywire’s energy comes from the visual metaphors drawn by the actors onstage through daring stances and movements. The two actors, Tafadzwa Bob Mutumbi and Lisa Gutu did a pretty good job in representing the spirit of the production that delves into such a sensitive matter that is often ignored in communities. Everson Ndlovu the director of Haywire believes the adopted style of storytelling which leans more on physical theatre serves a specific purpose, “As a theatre maker I am interested in expressing the inexpressible and I believe the piece is doing exactly that. We are experimenting with thoughts, feelings and emotions figuratively, making the performance physical and highly engaging.”

There is definitely no doubt that Haywire is a well-performed profound piece that mirrors a societal ill but it has to be stressed that it’s tightfisted when it comes to comic relief. It’s a dive into a somber space where many are uncomfortable visiting. Here the sun shines dimly, roses are pale and humanity is vulnerable to the torments of inner ghosts. After the three-day run in Harare Zimbabwe that stretched from the 14th to the 16th of March, the producers are optimistic about the possibility of touring with the theatrical production within the region and beyond.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Tawanda Mupatsi.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.