Namsan Arts Center’s 2017 season opened with Censoring the Minority 2017 (written and directed by Lee Yeon-joo), a revival of a production that was originally part of the Project for Right 2016 festival. Many wondered if the piece would be relevant outside of the Project for Right initiative, as the context changes depending on whether it is staged among a series of productions about censorship or presented on its own. As I did not see the premiere, I am unable to compare the quality of the two versions. Yet I saw no problem in staging Censoring the Minority separately. The production’s message was clear; it had no trouble reaching out to the audience.

Unlike the premiere, however, the reception was divided. Looking at Seoul Theater Center’s online “flower ratings,” most theatre professionals were relatively generous while general audiences were not. Some bloggers posted negative reviews. In general, these spectators applauded the production’s goal of listening to the voices of gender minorities, but had issues with its structure and the depth of its critical perspective, as well as its artistic merits.

A Sincere Self-Portrait of Gender Minority Teenagers

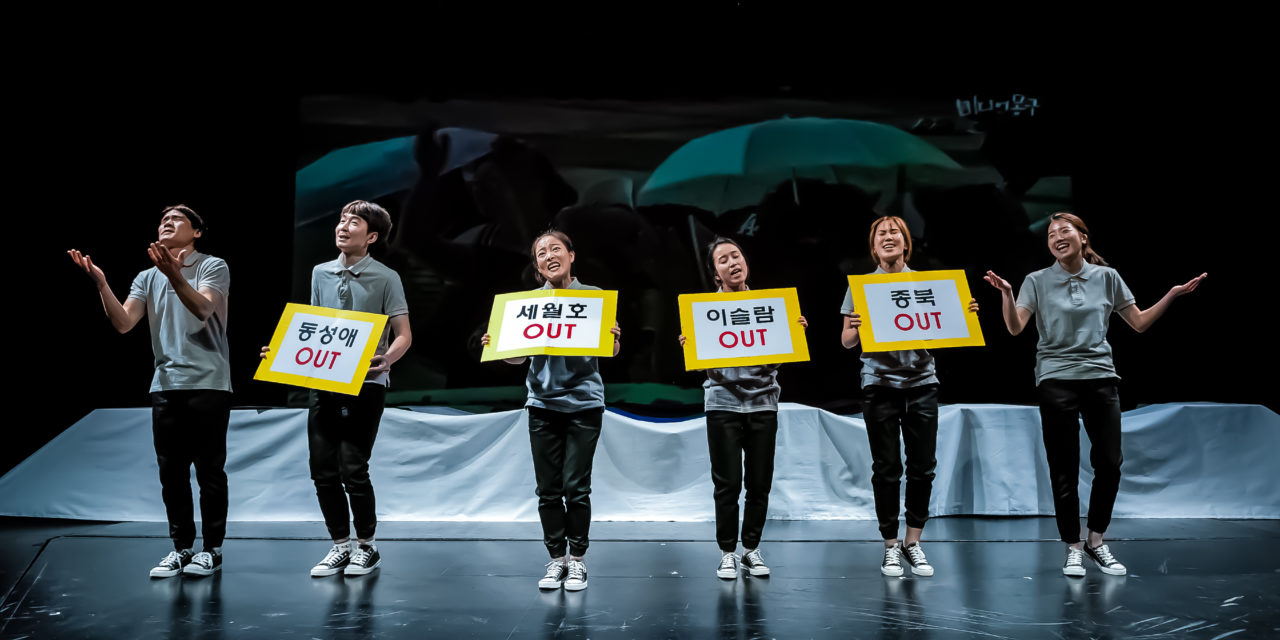

Censoring the Minority 2017. Photo courtesy of Namsan Arts Center.

In her previous work The Phone Rings, Lee Yeon-joo showed off her talent for capturing the little details of reality, depicting the lives of call center workers with both weight and energy. Frankly, I expected a similar attention to details in Censoring the Minority 2017. Although formally different from her earlier play, I believed that this work of documentary theatre could also achieve a sense of everydayness through meticulous representation, and make it emotionally resonant and moving.

At the start, actors perform edited interviews of actual gender minority teenagers. The actors partly exist as vessels, diligently relaying “real words” rather than characters, as if they were in a staged reading. Perhaps this project began when its creators were captivated by a reality more surprisingly theatrical than fiction, as is often the case in documentary theatre. The interviews were exceedingly quotidian. Although we don’t hear the questions, I could guess what the interviewees were asked: “When did you become aware of your sexual identity?”; “Do you get along with your parents?”; “What is school life like?”; and so on. The answers give us a glimpse of what gender minority teenagers think in gentle, nuanced language, with little mention of shocking incidents. A sincere self-portrait of South Korean gender minority teenagers begins to emerge.

The production takes this approach to portray these teenagers as truthfully as possible without distorting or exaggerating their stories. The director objects to the media’s gaze, painting them as gloomy delinquents on the fringes of society. Her approach succeeded to a degree. The portraits seemed healthy at first, coming alive through the actors’ bright and cheerful attitude, as well as their precision that, at times, read as discretion. They did not seem different from “normal” teenagers. At the same time, overemphasizing their ordinary experiences weakened their specificity as minorities struggling with discrimination and injustice. The everydayness of the interviews focused too much on the superficial and exterior aspects of their lives; missing were the delicate emotions that hit home. What, then, does Censoring the Minority 2017 want us to reflect on besides recognizing that “they exist just as we do”?

It was also unclear what kind of relationship the actors as mediums wanted to create with the audience at various moments. The “real words” that the actors transmitted were supposedly things that South Korea’s gender minority teenagers wanted to say to the audience. But they weren’t powerful enough to make people realize something that they had not known before, or generate more curiosity, sympathy, and love towards them. The production was inspired by the documentary film Lesbian Censorship in School. Although I did not see the film, I don’t think that the production succeeded in translating into theatrical language the presence and emotional force of a documentary film about real people.

Censoring the Minority 2017. Photo courtesy of Namsan Arts Center.

Was the Proliferation of Hate Effective?

Censoring the Minority 2017 calls attention to the stigmatization of gender minority teenagers in an episode of the television program The Its Know from the 90s, as well as actual cases of schools routing out gay and lesbian students. After the first half, which consists of interviews, the production explores various forms of censorship in the media and everyday life. Questionnaires with items such as, “List any friends whom you suspect may be homosexual,” are cringeworthy. By placing the gaze of the many after the teenagers’ own narratives, the piece jarringly exposes our society’s inclination towards authoritarianism and everyday manifestations of exclusion and discrimination.

As an audience member and as a part of the majority in South Korean society, this performance forced me to confront a familiar emotion: hatred. The piece suggests that the question, “Who produces hatred?,” is no longer important, as the target of hatred continues to exist under countless names: women, foreign workers, people with disabilities, gender minorities, North Korean “spies,” and so on. What’s important is the effect of that hatred. The production warns us that hatred hinders public discourse, denies the existence of social minorities, and prods society towards bizarre solidarity and abnormal totalitarianism.

The scene in which a giant South Korean flag covered the entire space symbolized this. Though the production did not represent a specific space, it suggestively used classroom chairs as props. The classroom chairs, lined up in a neat row, tell us that hatred is passed down through convention like the things you learn at school. Like the South Korean flag that later enveloped the chairs, this hatred grows to immense proportions. Or perhaps the giant flag represents the call of hatred that must be heeded for the sake of national unity. The communitas that brings us together originates in none other than the exclusion of minorities.

Censoring the Minority 2017. Written and Directed by Lee Yeon-joo. Photo courtesy of Namsan Arts Center.

Ultimately, Lee’s approach seems to have been more successful in last year’s Project for Right initiative than Namsan Arts Center’s current season. The mise en scène was changed to fit the new performance space. Audiences also responded better to the overarching theme of “rampant censorship” in last year’s production. The piece made an impact because it expanded the notion of policy-led state censorship to various forms of censorship in everyday life. But in Censoring the Minority 2017, broadening the scope of hatred from gender minorities to women, foreign workers, and North Korean spies ended up dissolving the differences among these groups, weakening the points of conflict rather than adding up to a larger theme. This can end up becoming another form of minority erasure. Moreover, the “history of hatred” narrative was too superficial to be dramatically persuasive, making the piece feel similar to other productions that have dealt with modern Korean history.

Still, the production successfully took a topic that can easily come off as preachy and abstract and examined it through a variety of documentary theatre techniques rather than rely on straightforward representation—especially impressive because it deviated substantially from the techniques in Lee’s previous work. Although it was not particularly stylish, it used music effectively and had a great sense of rhythm that balanced out the scenes.

Striving to Tell the Stories of the Erased

After showing us a sincere portrait of gender minority youths and the spread of hatred throughout society, Censoring the Minority 2017 shifted attention to other voices being erased: those of the bereaved families of the Sewol Ferry disaster in 2014. Towards the end, the production returned to the first sequence, this time relaying interviews with the Sewol disaster families instead of gender minority teenagers.

This ending was controversial. Many people asked how gender minority teenagers and the families of Sewol victims could be treated the same. One could say that the piece refocused on other social minorities and targets of exclusion. But it is hard to agree that the Sewol families are erased through the violence of the majority like the other excluded groups.

Nevertheless, Censoring the Minority 2017 reflected Lee’s deep conviction and care for her subject matter. Although the production was not as structured and polished as her previous work, she stuck to the unfamiliar vocabulary of documentary theatre from beginning to end. The piece was also empowered by her desire to fight discrimination, exclusion, and hatred perpetrated every day in the press and media, in school, and by our friendly neighbors. Finally, Lee’s efforts to listen to erased voices imbued the production with a hopeful and warm energy. I look forward to her next work.

Um Hyun-hee is a theatre critic interested in outdoor performance, non-verbal theatre, theatre for young audiences, and new creative processes.

Translated and edited by Kee-Yoon Nahm

This article was originally published in Korean Theatre Journal, the official journal of the International Association of Theatre Critics – Korea. Reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Um Hyun-hee.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.