Nuria Espert turns 89 today. Hers has been an extraordinary career and it’s not over yet. She has just spent over 13 months on tour with La isla del aire/The island of the air, a new play adapted by Alejandro Palomas from his acclaimed 2005 novel, directed by Mario Gas. She animated the stage, as a wily grandmother, first appearing infirm and fragile in a wheelchair but soon displaying a fierce, defiant energy that holds her family together – a witty, nuanced performance of exceptional deftness. And this autumn, she will open another production, again directed by Mario Gas, Todos pájaros/All Birds by Wajdi Mouawad at Madrid’s Teatros del Canal. And all this comes after an extended tour of Lorca’s Romancero gitano/Gypsy Ballads, first presented in 2018, a solo piece directed by Lluís Pasqual as much about her relationship with Lorca’s plays over close to fifty years as it was a performance of some of his most celebrated poems. To hear Nuria Espert give form to Lorca’s work is something unique – in a breadth and a whisper, she gives urgency to the verse. It is as if she has a story to tell, something she must confide in the audience. Espert makes Lorca matter as something urgent, timely and unique.

Nuria Espert is an extraordinary actor – her voice rich and resonant, her stage presence both grounded and ephemeral – if ever you needed a definition of duende, that thrill of the live that Lorca spoke of, Nuria Espert embodies it. For over seventy years she has been making theatre – from the amateur working class theatres of Barcelona to Madrid’s Centro Dramático Nacional, touring across Spain and internationally with productions that provided fresh, dynamic readings of key twentieth-century plays.

As an actor Nuria took risks, setting up her own theatre company with her husband Armando Moreno in the late 1950s. Here she staged new pieces for the first time in Spain, working both with notable directors of the time, like Cayetano Luca de Tena on Gigi (1959) and José Luis Alonso on Desire Under the Elms (1962). Onstage Espert was a force to be reckoned with, embodying an impressive range of roles that displayed female agency in multiple forms. From Hamlet (1960) to Lavinia in Mourning Becomes Electra (1965) – Nuria provided a stage presence that defied the compliant image of the devoted wife and mother that the Franco regime (1939-75) sought to promote. Nuria Espert excelled at presenting women who refused to compromise.

During the democratic era she collaborated with Spanish directors across different generations — including Lluís Pasqual, Mario Gas, and Miguel del Arco. She also internationalised Spanish theatre, firstly by bringing directors like Víctor García and Jorge Lavelli to a country that had been isolated under the Franco dictatorship and then from the 1990s onwards forging new collaborations with Robert Lepage on Celestina (2004), George Lavaudant on Play Strindberg (2006) and Peter Sellars on Ainadamar (2012).

And while she is a very great actor, she is also so much more than that. A translator, adaptor, director and producer, she pursued a career as an actor manager that was defiant and courageous. And while she is lauded in Spain as one of the country’s greatest actresses – part of a tradition that reaches from María Guerrero to Margarita Xirgu and María Casares, her global impact cannot be underestimated. She placed Spain on the international map with her collaborations with the Argentine Víctor García. With García she forged a stage vocabulary for The Maids (1969), a reading that found a formal, anti-realist language for Genet that was bold, in-yer-face and uncompromising. To recall the Espert-García Yerma (1971) is to be taken on a journey of spiralling desperation and longing – the canvas trampoline designed by Fabià Puigserver capturing the undulating moods of the play. And Divinas palabras/Divine Words (1976) staged against the backdrop of a giant organ was similarly audacious in its realisation of a theatrical vocabulary for Valle-Inclán’s defiant 1919 play. Those productions are still recalled as groundbreaking by those who saw them when they toured in the early and mid-70s. For David Lan, former director of London’s Young Vic theatre, “that Yerma was unforgettable”, propelling his own commissioning of Simon Stone to render a new version inspired by the García production in 2017.

David Gothard, who programmed the Riverside Studios between 1976 and 1985 delineates that: “My generation thrills to its memories of Nuria Espert’s great performances. The memory is vividly imprinted with the genius of the Lorca trampoline and her Genet. It became important to include her in the early programming of the forming of Riverside Studios. It was typical of her generosity with artists in her life, such as her sharing the unique genius of Victor Garcia with the world, that she chose to present to an appreciative London audience, the essential poet and friend of Lorca, Rafael Alberti, towards the end of a life embodying the history of modern Spain. As his published poem puts it, “I hated London, all grey skies, but I fell in love with Riverside Studios and the Rokeby Venus [of Velazquez at the National Gallery]”. On his only previous visit to London he had been put into a cell upon arrival at Heathrow till Picasso flew in to demonstrate and rescue him, leaving on the next plane. Later this generosity of spirit of Nuria exploded down the road at the Lyric Theatre with the cream of British actresses achieving the spirit of Lorca in [The House of] Bernarda Alba in such a way that the British theatre has lived with this blessing ever since. Great acting and the spirit of Lorca, directed by Nuria. I recall the happiness of Lorca’s sister by Nuria’s side” (email to the author, 3 June 2024).

In 1981, her Doña Rosita, in a production by Jorge Lavelli, captured the protagonist’s emotional journey from the illusive joy of first love to the quiet despair of abandonment. Michael Billington, reviewing the production at the Edinburgh International Festival, wrote of “a great actress …. unafraid of the grand gesture” (Guardian, 31 August 1983). Espert embodied a female agency that was emotionally rich, gut-wrenching and complex.

In 1986, she made her directorial debut with The House of Bernarda Alba, first presented at the Lyric Hammersmith in 1986 and then transferring to the West End before being filmed for television in 1991. Dramatist Arnold Wesker holds Espert responsible for finding a stage language for Lorca in the UK and the production arguably opened up interest in a dramatist that had been seen as awkwardly foreign and difficult to produce. It also initiated a directorial career that incorporated operatic stagings as well as much as theatre: work that placed women’s sensibilities and journeys at the very centre of the readings. Productions of Madame Butterfly (1987) and La Traviata (1989) for Scottish Opera, of Carmen (1991) for the Royal Opera House were both painterly and thrillingly theatrical. When the new Gran Teatre del Liceu reopened in Barcelona in 1999 – the iconic opera house had been destroyed by a fire in 1994, Nuria Espert directed a pictorial Turandot to open the venue.

This year has seen two significant awards for Espert. An honorary Max — the Maxes are the Spanish equivalent of the UK’s Olivier Awards or the US’s Tonys — for “her great legacy in the area of the performing arts, her contribution as a cultural leader and as a theatrical entrepreneur”, and an Honorary Doctorate from the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama, University of London for a body of work that has had a far-reaching impact on theatrical practice both in Spain and the UK. At the ceremony for the latter at the Spanish Ambassador’s Residence in London, I was struck by the warmth of the reception she received from the actors who had worked with her in that now legendary production of The House of Bernarda Alba. There was a great humanity evident in the encounter – Espert has always spoken of herself as an emotional rather than an intellectual director — and as Amanda Root (Adela), Deborah Findlay (Martirio), Julie Legrand (Angustias), Suzanna Hamilton (Amelia) met with her, joined by the National Theatre’s most recent Bernarda, Harriet Walter, I gained a sense of how special that rehearsal room must have been as the production and then the film were prepared with love, care and respect. The complicity that had generated that extraordinary production was still evident, 38 years on. Nuria was thrilled to spend time with them – “that production was so special”, she commented to me afterwards. The actors concurred: for Deborah Findlay “I think our production of Bernarda Alba is etched on all our hearts” (email to the author, 3 June 2024); actors past and present who have grappled with Lorca’s world sharing what that means and how to give form to the Lorca’s precise language. Julie Legrand wrote to me in the aftermath of the event that “Nuria is exactly as she always was – inspiring, dynamic, passionate, brave, generous, open, and vibrating with life – she’s a magnificent inspiration! Time hasn’t diminished her at all” (email, 20 March 2024). Seeing Nuria with these actors, and the messages they have shared with me consequently, brought home how much she sees theatre as a collective endeavour.

Harriet Walter, Amanda Root, Nuria Espert, Deborah Findlay, Julie Legrand and Suzanna Hamilton at the Residence of the Ambassador of Spain, HE José Pascual Marco. Photo: Patrick Baldwin

There is always labour for Espert in the process of making theatre, always discipline but also with the space for instinct where the unexpected is always welcomed and nurtured. Espert’s humility and warmth is never far from the surface in any encounter. Nuria Espert understands that theatre is about people who come together to make and experience work; that humanity is core to an understanding of everything she does on- and off-stage.

Nuria Espert receiving the Degree of Doctor of Literature (Honoris Causa) conferred by Central. at the Residence of the Ambassador of Spain, HE José Pascual Marco. Photo: Patrick Baldwin

Michael Billington, reflecting on the award of the doctorate writes that: “I have always believed that a life in theatre is the best way of staying young. Seeing Nuria at the Spanish Embassy in London this March, I was struck by her blazing energy, joy in life and timeless beauty. Her impact on British theatre has also been profound. It was through her astonishing work in Yerma and Dona Rosita the Spinster that we began to grasp the greatness of Lorca as a dramatist. Nuria is not only a force of nature. She is also a great actor” (email to the author, 3 June 2024).

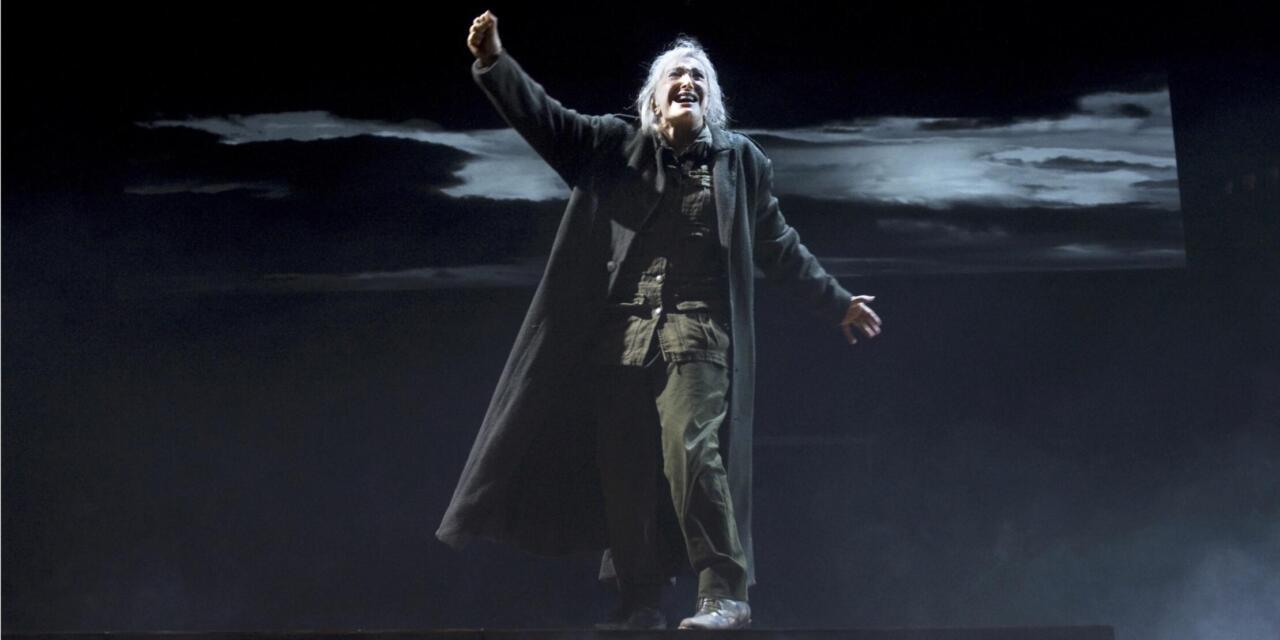

So Nuria Espert — a great actor and a force of nature — on your 89th birthday, I raise a glass to the pleasure you have given to those of us who have watched your exquisite performances, performed with you, and experienced your methodical, precise direction. Your resonant, melodic voice once heard is never forgotten. With the lifting of an eyebrow, the slight shift of your head or a stern glance you transport the audience to a special place, a journey into a text, a character, a process. As I write this, memories of your Lear come to the fore: you performed the role at close to 80 in 2015 and it was remarkable, a production where dementia was placed at the very centre of the reading, inspiring your great friend Glenda Jackson to embark on her own Lear with Deborah Warner soon after. You have never been afraid to be fearless on and off stage and remain an example to so many of us of the transformative power of live performance to challenge, to defy and to inspire.

Nuria Espert as King Lear, directed by Lluís Pasqual at the Teatre Lliure, Barcelona (2015): Photo: Ros Ribas

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Maria Delgado.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.