Current plays treat the great global contexts, but also take a look at family structures.

There are still traditional plays, written in solitary hours at home by a single author. Alongside this clearly defined sort of text, however, the origination of theatre text has taken ever more winding paths. For example, The Situation at Berlin’s Maxim Gorki Theater was developed by the Israeli director Yael Ronen together with performers so as to reflect the reality of the lives of immigrants in Berlin who come from various crisis regions of the “Middle East”. In the case of a documentary play such as Gesine Schmidt’s Pfirsichblütenglück (Peach Blossom Happiness), the text is composed of transcripts of interviews and aims to be nothing more than a literal reflection of individual realities. Premièred at the Heidelberg Theatre, it tells of bi-national couples who, in spite of the strangeness of different cultures, seek happiness together.

Andreas Seifert (Holger), Nanette Waidmann (Huang), Gustaf Gromer (Xu), Nicole Averkamp (Brit), Dominik Lindhorst-Apfelthaler (Jan) in Gesine Schmidt’s Pfirsichblütenglück (Peach Blossom Happiness) Foto Annemone Taake

All these theatre texts, regardless of how they were written or developed, are fuel for festivals such as the Mülheim Theatre Festival and the Heidelberg Play Market. In the 2015/2016 season, about 110 texts were premièred. Of these, just about twenty were so compelling that they were discussed by the selection committees and juries. A survey of the plays’ subjects confirms an observation about previous seasons: authors and collectives are treating the conflict areas of globalized modernity and venturing to take a look at family structures as well as at the great global contexts.

POVERTY PIRACY

Above all, however, the authors write not only discursive but also narrative theatre literature. This is especially true of Lächerliche Finsternis (The Ridiculous Darkness) by Wolfram Lotz. It is the play of the 2015/1016 season that has had the widest appeal and been performed, after its première by Dušan David Pařízek in at the Vienna Akademietheater, with a frequency that is otherwise enjoyed only by the works of Elfriede Jelinek. Lotz has dared to take the biggest step in the direction of dislocating the narrative world from reality and treats the hybris of the European colonizers who, among other things, exploited the black continent and are co-responsible for the poverty piracy along the coast of Somalia.

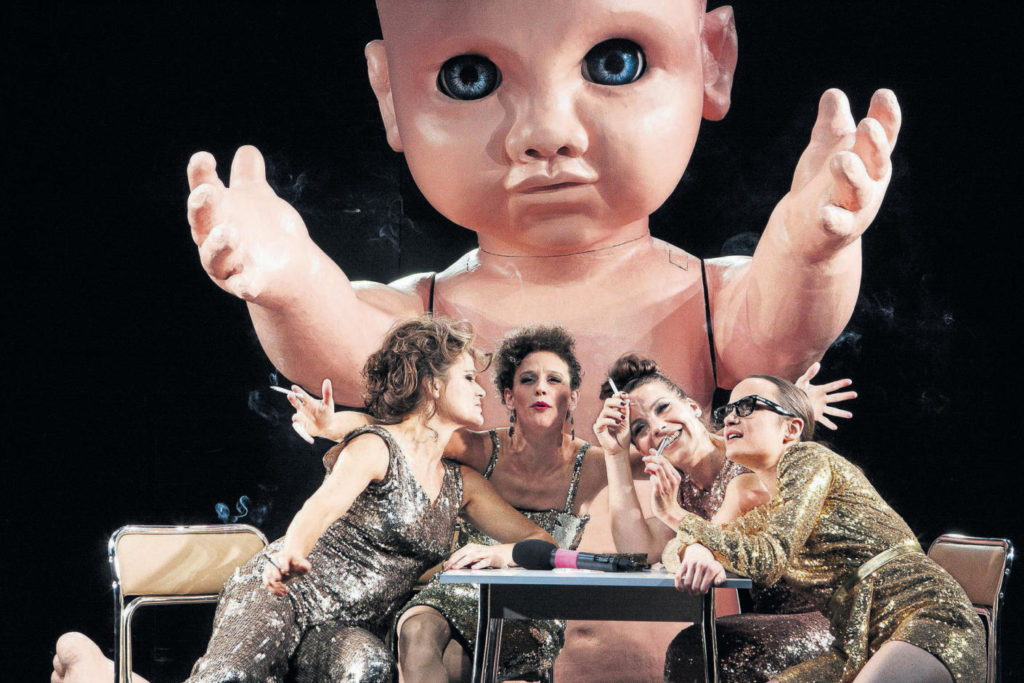

Stefanie Reinsperger, Catrin Striebeck, Frida-Lovisa Hamann, Dorothee Hartinger in Lächerliche Finsternis (The Ridiculous Darkness) by Wolfram Lotz, Vienna Akademietheater / Burgtheater Vienna | © Reinhard Werner

As narrative foil, Lotz takes Joseph Conrad’s colonialism classic Heart of Darkness and the film Apocalypse Now, Francis Ford Coppola’s journey into the gloom of the American war in Vietnam. Lotz’s text was for theatre a starting-point that made it possible to reflect on the mass refugee movement from Afghanistan, Iraq, the Middle East and Africa to Europe. Rebekka Kricheldorf, on the other hand, provided theatres with a play in which Europeans flee their reality to the exotic regions of the world. In der Fremde (In Foreign Parts), premièred at the Deutsches Theater in Göttingen, is about the sex business.

WEALTH GAP

Kricheldorf too aims at presenting the big picture and shows well-heeled Westerners at a bar that could be in Kenya, the Dominican Republic or Thailand. A professor, availing himself of the business model of the sugar daddy, travels with a young student, while a lady of a certain age enjoys the bodies of young “natives.” The travellers from rich Western countries delude themselves into thinking that, beyond the economic realities of their homelands, they can buy love with money.

Rebekka Kricheldorf’s In der Fremde (In Foreign Parts), Deutsches Theater in Göttingen | Photo: Georges Pauly

In der Fremde reflects the ever-growing wealth gap in the world and the resultant conflicts in the twenty-first century. The calculation is simple: some have money, others have only their bodies or an ideology such as Islamic jihad. In Stück Plastik (A Piece of Plastic), Marius von Mayenburg also takes up the theme of the ever-widening gap between rich and poor, but situates his theatre text in the microcosm of a Berlin household and deploys the genre of classical comedy.

PRECARIOUS REGION

Stück Plastik, which was premièred under the author’s direction at the Berlin Schaubühne, shows a married couple of the upper middle class. They give themselves out as overworked, but are above all vicious and hire household help from a precarious region of the Federal Republic. The new help is not only a rubbish chute and soul-comforter, but also unmasks the mendacity and hypocrisy of the better-earning part of the population. Mayenburg presents the comic side of the erosion of what used to be the educated upper middle class. Sibylle Berg adjusts the focus even more sharply and concentrates on a sub-unit of the family model. Her play Und dann kam Mirna (And Then Came Mirna) is about a single mother, her daughter and the paradox that the daughter is a strong personality and shows the mother what it’s all about.

This satire on the crisis of meaning of the contemporary parent in burn-out mode was premièred at the Maxim Gorki Theater in Berlin and is the domestic variant of the hyper-nervous effusiveness of a Western modernity that evinces itself on the autobahn in the form of horsepower-intoxicated dominance and mass collisions. The play on this theme is Ferdinand Schmalz’s dosenfleisch (Tinned Meat). This autobahn blues for people who are underway with accident, liability and otherwise insured crash potential, was premièred at the Vienna Akademietheater.

Tino Hillebrand (rolf), Frida-Lovisa Hamann (jayne) in Ferdinand Schmalz’ dosenfleisch (Tinned Meat), Vienna Akademietheater / Burgtheater Vienna | © Reinhard Werner

Translated by Jonathan Uhlaner

This article was originally posted on Goethe.de. Reposted with permission. To read original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Jürgen Berger.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.