Karnad spoke about his life as a writer and cultural administrator, his accidental foray into cinema and the state of Kannada literature.

“Look at that… at the end of the branch, it is… It’s a fruit bat, which is sucking from a mango fruit. If it flies you’ll see the mango… ah there, it’s gone.”

The voice, despite the tired rasp, is unmistakable.

“It’s been great fun writing plays I must say.” That is Girish Karnad, speaking with writer and translator Arshia Sattar and filmmaker/ educator Anmol Tickoo in a series of conversations that took place just a few days before his death on June 10, 2019. Sitting on his terrace, fitted out “with an oxygen tube in his nose and an oximeter on his finger,” Karnad spoke about his life as a writer and cultural administrator, his time with Sangeet Natak Akademi, his accidental foray into cinema (“I was never interested in films, I hated films”), and the state of Kannada literature and theatre.

Two-year pursuit

The recordings form the backbone of a new podcast series from the Bangalore International Centre, anchored by Sattar and Tickoo, and supported by the Nilekani Philanthropies. As Sattar explains in the introductory episode of The River Has No Fear of Memories the meetings resulted from a two-year pursuit in which Karnad consistently refused to commit, until suddenly one day, he agreed to what was to remain an unfinished attempt to document his recollections. But what they did capture is substantial, offering a glimpse of the prodigious oeuvre and how it came to be.

Karnad’s remembering voice is supplemented by fellow travellers in Kannada theatre and literature — Vivek Shanbag, Shantha Gokhale, and Sunil Shanbag, among others — who lend context and perspective to the memories. “Certain themes kept cropping up in these conversations,” recounts Sattar. “Kannada literature, Indian theatre, existentialism, being a public intellectual, the art and craft of playwriting.” The nine episodes that make up the series will unfold around these themes, making up an oral history of sorts that a student of contemporary theatre or literature will find much to learn from. Interspersed through each episode are short enactments from Karnad’s plays, rendered by Bengaluru theatre artistes.

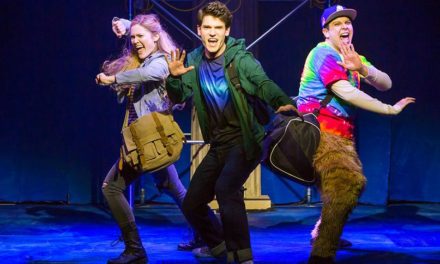

A scene from Nagamandala here, another from Hayavadana there, a short reading from Broken Imagesthat raises the question of authenticity and a writer’s motivation. These short interjections bring Karnad’s work alive and serve as a teaser for those who may not be familiar with it. There is a bit of backstory for each — Karnad talks a bit in this introductory episode about how he came to what is perhaps his most famous play, Tughlaq, a take on the mad monarch that remains a fable for our times.

Admittedly, the tone of the podcast is celebratory, with Sattar and Tickoo playing the admiring narrators with exchanges that can, at times, sound a bit self-conscious. At one point, Sattar comes close to gushing, “Oh, Nagamandala… is my most favourite play!” But there is a quick pivot to a reading of the play that takes us to the source of the wonder and invites us to share in it.

The River Has No Fear of Memories combines the art of biography with cultural history and packs it into a podcast, making good use of the medium. The haunting theme music, drawn from a song in Hayavadana, leads us in and out of each episode, feeling a little bit wistful for something that is no more, but grateful for what has been given.

The Hyderabad-based writer and academic is a neatnik fighting a losing battle with the clutter in her head.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Usha Raman.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.