The critical responses to Taylor Mac’s debut, Gary: A Sequel to Titus Andronicus, have been all over the place, from huffy dismissal to ardent encomium. I, for one, was too fascinated by what the show was trying to accomplish to think about a simplistic thing like thumbs up or thumbs down. Gary is a romp that tries to steer its laughter toward big questions. The big question it left me brooding on more than any other was the difference between superficial and radical queerness.

I’m among those who think of Mac as a national treasure. His marathon work A 24-Decade History of Popular Music two years ago was the most fun I’ve had in the theatre in decades and the strongest political use of the theater I’d seen since Angels in America. [Note on pronouns: I use “he” and “him” rather than Mac’s preferred pronoun “judy” because I’ve heard him accept “he” and “him” in interviews, and because for me making sentences work with “judy” is impossible.]

Mac is the only American theater artist I’m aware of who’s currently working on the epic scale of Tony Kushner. His 24- Decade piece was electrified by his incomparable performing persona: a lavishly flamboyant, politically conscious drag act that drove the show’s surging, jolting communal-immersion experience. Framed as a concert, the 24-Decade History was a revelatory and original history of the United States, rigorously scripted to appear messy and impromptu.

The show took audiences by surprise by treating brassy queerness as an alternative, radically inclusive American value system: a trope for openness, objectivity, and fairness that don’t collapse under challenge. Mac applied his value system to an astonishing range of historical figures and events- from Thomas Paine, Mary Baker Eddy and Ted Nugent to the Trail of Tears, abolitionism, minstrelsy, Jim Crow, the Opium War, Reconstruction, the Oklahoma land rush, and much, much more- turning his fearlessly queer world view into a compelling sort of common sense. Queerness became a clarifying lens you were sorry to relinquish when you left the theater because it made everything appear lucid, funny, ethically sane, and negotiable.

The plays Mac has written but doesn’t perform in don’t have the same miraculously radiant core. They are way more interesting than the bulk of what gets professionally produced- ambitious, smart, hilarious, formally inventive- but they don’t burn quite as bright. Queerness in them is typically a choice of certain character pressured by quasi-comic situations that threaten to clip their wings and snuff out their innovative light.

In Hir, for instance, Mac’s family-play satire produced by Playwright’s Horizons in 2015, gender-queerness was a tool of revenge. Kristine Nielsen played an abused housewife who got even with her battering husband, after he was incapacitated by a stroke, by injecting him with estrogen and dressing him in women’s clothes. A gender-fluid teenage daughter (renamed Max) asked mom some tough questions about her actions and motives but was too young and clueless to serve as an ethical compass. Queerness in Hir thus came off as an unkempt moral promise.

In Gary, Mac sticks with a positive spin on queerness but its affirmative power was limited by heavy helpings of decidedly conventional comedy. Nathan Lane, in the title role, plays a clown who miraculously survives the slaughter in Shakespeare’s ridiculously bloody Titus Andronicus, gets a job helping to clean up the mess, and then sets out to quixotically overturn the whole rapacious and patriarchal value system of the Roman Empire by using the huge mountain of corpses piled around him as props in a monumental performance artwork called a “fooling”.

What could be queerer? The thing is, on the way to organizing this world-saving project Gary spends more than a half hour entertaining his stage partner (Kristine Nielsen) and us with shtick: a farrago of fart, poop, and piss gags employing the dummy corpses whose essence comes straight from his branded repertoire of moues, yucks, and nyangs, and her repertoire of bug-eyes mies and goonish double-takes. The bulk of it is standard gross-out humor. Also, Nielsen’s character Janice- a maid who just wants to get on with the cleaning- is for half the play just a comic obstacle to Gary’s rebellion. He eventually wins her over with the stock (and rather unprogressive) comic device of appealing to her vanity (she starts seeing things his way after trying on the corpses’ expensive jewelry and clothes).

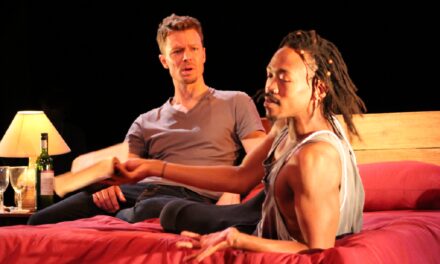

Photo Credit: Julieta Cervantes

Now, I thoroughly honor the difficulty and talent involved in pulling shtick off. And yes, I laughed. With an artist of Mac’s caliber, though, you have to ask whether his work is firing on all cylinders and has the conditions it needs to maximize its political traction.

Gary is a rare bird on the Great White Way. Laura Collins-Hughes said at the terrific TheaterMatters panel this week where we discussed it with Marc Robinson and Michael Rogers: “This is as subversively political as Taylor Mac’s other other works, and I just found it heartwarming that it’s on Broadway.” [Click here to listen to the recording.] I share Laura’s thrill at seeing it at the Booth Theatre, and its Tony nominations, and at the prospect of Mac earning a pile of money. I don’t agree, however, that the show is as subversive as it could have been, or as Mac’s performed works have been.

Gary strongly reminds me of another experimental, rebarbative, yuck-filled drama that amazingly found its way to Broadway- twice, in fact- without ever being truly popular: David Hirson’s cult hit La Bete. Like Gary, La Bete used rhymed verse self-consciously to pose questions about high and low art and centered on a mad comic performer whose primitive, chaotic force pointed to the destruction and redemption of theater all at once. Interestingly enough, both plays also culminate in a distended, over-the-top monologue by this central comedian that describes his dubious triumphal vision.

Here is a section of Gary’s monologue, his epiphanic vision of the great, redemptive “fooling” he foresees as “an artistic coup” and “a comedy revenge to end all revenge.”

…it’s gotta have all the history in it. All the conflicts. Like you said, put all the murder and mayhem in one place so they can see what’s what. What they’ve been. What they could be. Which means we gotta squeeze all the sequels of revenge in. We gotta theatricalize the sequels after the sequel after the sequels. And all the orgies of hyperbole, the grabbing of privacy and privates, takeovers, tantrums, endless campaigns, pillaged elections, apocalyptic weather-spewing-forth-shark-attack-family-feuds! Yes Janice, shark attacks. There must be wars in stars, and geriatric stars at war. Heroes must battle heroes, winged rodents must clash with cleft chins, there must be an explosion of an explosion, a massacre of a massacre, and ensemble of an ensemble, to such a ridiculous degree ya can’t see anything but its ridiculousness. And Janice, when the court sees it, they’ll be a little taken at first. There’ll be a moment of silence, don’t kid yourself. But then, in the distance, one soul will feel a bubbling finding its way to their hands. “What am I doing,” they’ll wonder. “Why am I clapping?” And they’ll realize. They’re clapping for hope. And soon it spreads. Not just one court member but two. Then more. Row after row, gaining speed, soon all the court, the clapping turns to cheering, then standing on their feet, on chairs, reaching ever higher to touch the ingenuity that could be theirs as well.

This is like a Taylor Mac manifesto. The speech’s playful language articulates a maximalist aesthetic that outdoes all spectacles (and spectacle-exhaustion) of the media age and regards the world as a giant political stage filled to bursting (and thus changing) by a formally powerless, queer-minded comedian suddenly endowed with infinite theatrical resources. The vision is meant to be inspiring. Stupefying. Seductive.

Except… it fails to materialize. You kind of expect that all the impossible Artaudian excess won’t prove possible but you do expect Gary to at least keep his promise to “put all the history” into the performance he creates- as Mac astonishingly, unforgettably DOES in his 24-Decade History. That doesn’t happen. Instead, Gary settles for historyless shtick and a climactic musical number in which stripped dummy corpses dance obscenely via a crazy Rube Goldbergesque mechanical contraption.

For me, the closest the play came in the end to genuinely biting critique was in its prologue, when the third character, Carol- a midwife played by Julie White- delivers a speech in verse, with blood spurting out of her severed neck, asking whether “gore” and other sensationalistic “thrills” can ever avoid becoming “routine”.

Photo Credit: Julieta Cervantes

Radical queerness, I realized, is when an outsider artist speaks truth over power unignorably by transforming himself into a fool so brilliant his subversive political critique wins national awards and gets him on Stephen Colbert. Superficial queerness is when a fictional clown who aspires to be that sort of fool is played for slapstick laughs by Nathan Lane on Broadway.

Superficial queerness is moving penises from left to right on Roman soldier dummies who dance and grow erect and calling that a revolution. Radical queerness is making the world safer, freer and more inclusive for the owners of actual left-leaning penises (and brains).

Superficial queerness is using camp to tweak the noses of straight people Radical queerness is using camp to make everyone- queer, straight, and otherwise- see the world more fully and clearly, way beyond their noses.

I don’t take lightly the appearance of pointedly rancid satire like Gary in a ruthlessly commercial environment notorious for flattening every sharp political provocation it handles into easily digestible bromides and feel-good morals. Mac is no ordinary artist, though, and it’s his own fault that some of us have come to expect the world from him.

This article was reposted with permission from jonathankalb.com and was originally published on May 17th, 2019.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Jonathan Kalb.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.