In his 400th anniversary year, Shakespeare is still rightly celebrated as a great wordsmith and playwright. But he was not the only great master of dramatic writing to die in 1616, and he is certainly not the only writer to have left a lasting impact on theatre.

While less known worldwide, Tang Xianzu is considered China’s greatest playwright and is highly revered in that country of ancient literary and dramatic traditions. With the aim of exploring the common ground between these two masters, a series of productions from China and the UK are to be performed over the coming months to celebrate their lives and literary legacies.

Tang was born in 1550 in Linchuan, Jiangxi province, and pursued a low-key career as an official until, in 1598 and aged 49, he retired to focus on writing. Unlike Shakespeare’s substantial body of plays, poems and sonnets, Tang wrote only four major plays: The Purple Hairpin, The Peony Pavilion, A Dream under a Southern Bough, and Dream of Handan. The latter three are constructed around a dream narrative, a device through which Tang unlocks the emotional dimension of human desires and ambitions, and explores human nature beyond the social and political constraints of the feudal system of the time. It is a similar dream motif that we find in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

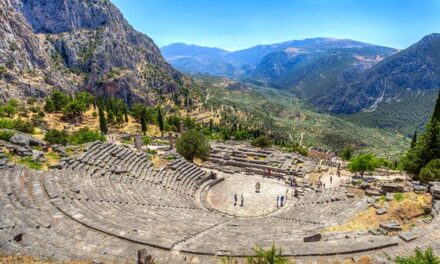

Zhejiang Xiaobaihua Yue Opera Troupe interweave Shakespeare’s tragedy Coriolanus with Tang Xianzu’s love story The Peony Pavilion. Performance Infinity, Author provided

The Peony Pavilion is considered Tang’s masterpiece. Over 55 scenes it explores the passions of young Du Liniang, daughter of Du Bao, the governor of Nan’an. After dreaming of a young scholar she meets in a peony pavilion, Du Liniang suddenly falls ill. Before dying, she leaves a self-portrait of herself and a poem with her maid, with orders to hide these under a stone by the plum tree at Taihu Lake.

Three years later, a scholar named Liu Mengmei dreams of Du Liniang. In his dream, he and Du Liniang fall madly in love. It is the strength of this love that helps Liu Mengmei to revive Du Liniang from the grave. After confronting Du Liniang’s father, the couple marry and live a long and happy life.

The distinctive aspect of The Peony Pavilion is Du Liniang’s life and death. The fact that a female heroine in a society dominated by moral obligations and a strict hierarchical order can pursue and accomplish her true love – defying even death – is no small matter. Echoing Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet with its theme of forbidden and endangered love, instead Tang’s play does not end in tragedy but with a message of hope that celebrates true love over death and the constraints imposed by society.

In Tang’s championing of qing (emotion) over discipline, and humanity over hierarchy and authority, we find common ground with Shakespeare. As is found in Shakespeare’s iconic characters such as Hamlet, Tang’s Du Lingnian is heroine of a great story in which she not only surmounts the challenges of her time, but in doing so creates a tale to survive the test of time.

An Eastern Renaissance

Tang lived towards the end of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) and, similarly to Shakespeare, his success rode the wave of a renaissance in theatre as an artistic practice. As in Shakespeare’s England, it became hugely popular in China, too.

Mainstream theatrical audiences started to populate open public spaces, and theatre as a popular form of entertainment found its place outside palaces and the gentrified circles of the literati. However, unlike in Shakespeare’s times, there was hardly any mixing of the gentry and rich with commoners at theatrical events.

During this time, the way in which play-texts were enjoyed, circulated and performed changed. Initially, Chinese drama had an emphasis on poetic language and a refined literary style, and were circulated as manuscripts to be read as if they were novels. They were seldom, if ever, performed. However, from the mid-16th century, kunqu opera, a form of musical drama, spread from southern China to become a symbol of Chinese culture.

While comparable to Western opera in terms of narrative and structure, kunqu differs in its physicality. Drawing from the Kunshan (near Suzhou, in modern Jiangsu Province) musical tradition combining northern tunes and southern music, kunqu opera encompassed poetic language, music, dance movements and precisely coded gestures.

Tang’s work arrived in the midst of this tension between formal poetic refinement and operatic, musical forms of theatre, and was at the centre of these theatrical debates. By the arrival of the Qing dynasty, a play-text was considered as a structure for music and singing, but Tang maintained that poetry and emotion were at the heart of his drama, and he was very critical when his work was adapted in order to suit the operatic style of the day. However, differences aside, Tang’s work benefitted greatly from the popularity of adaptations, and his play-texts are considered kunqu classics.

While Tang and Shakespeare lived a world away from each other, they share in common the humanity of their drama, their iconic, heroic figures, their love for language and poetic lyricism, a lasting popularity – and the anniversary during which we still celebrate them.![]()

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Mary Mazzilli.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.